Mar 30, 2017

March 2017: The month that changed the oil sands forever

Events over the past month will ensure the Canadian oil sands industry survives for decades to come, albeit as a shadow of its former self.

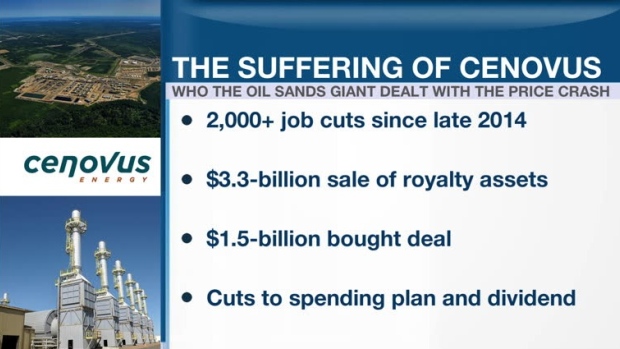

In March alone, two of the largest Canadian players ensconced in northern Alberta have spent more than $30 billion in cash and stock scooping up oil sands assets once held by international supermajors. Canadian Natural Resources announced on March 9 it’s paying $12.7 billion to all-but-buy out positions from Royal Dutch Shell and Marathon Oil. And late Wednesday evening, Cenovus announced its largest-ever acquisition. The Calgary-based company is buying out its Texas-based joint-venture partner – ConocoPhillips – for a whopping $17.7 billion.

Those moves do mean Canadians will control the destiny of the third-largest crude oil reserve on the planet far more than they have before. However, those moves will also mean little for the roughly 110,000 workers the Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers estimates have lost their jobs since the late-2014 crude oil price crash began.

Instead of using the recent price stabilization to hire some of those workers back in hopes of reviving the rapid growth plans producers had in mind before the crash (to wit: those growth plans were previously expected to create 100,000 new jobs over and above the sector’s existing employment) the industry has instead consolidated around existing assets. More than two years ago in an interview with BNN, former Suncor CEO Rick George – often called the godfather of the oil sands – predicted this scenario in what he described as a “cleansing” of the Canadian energy industry.

“In this scenario, most new oil sands projects can be deferred to a better day, and this is precisely what is happening,” Mike Tims told BNN on Thursday morning via email. The vice-chairman of Matco Investments, who previously spent three decades holding senior positions at Calgary-based investment bank Peters & Co before retiring as chairman in 2013, added “The bigger picture implication are many, however.”

“The prospect of refilling downtown Calgary office towers that are 25 per cent vacant, without employing the armies of engineers, project managers and service providers to build the large, new oil sands projects, which were to be a big industry growth engine, continues to look like a long-term challenge,” Tims said.

For the non-Canadian companies cutting ties with the oil sands, the argument for their all-but-abandonment of the space is simple. They took on massive amount of debt when oil prices were north of US$100 per barrel. As they now attempt to clean up their balance sheets, many are looking at the multibillion-dollar cost of entry in the oil sands – far higher than virtually anywhere else on Earth given the massive industrial complexes required as opposed to conventional drilling rigs – and ultimately deciding to deploy whatever capital they have left elsewhere.

“That does not mean that the Canadian purchasers, on the other side of these deals, are doing the wrong thing,” Tims cautioned. “The recent deals all involve fully-completed, cash flow-generated, high-quality projects bought at economic parameters well below benchmarks considered ‘normal’ prior to the downturn.”

“By definition, these oil sands projects also have high ‘option value’ if oil prices even partially rebound from current levels,” Tims said.

The risk, of course, is what happens if they do not. Raymond James notes Cenovus is going from having one of the best balance sheets in the business to one of the worst as a result of this deal, with Citigroup also pointing out it puts the company’s all-important debt-to-cash-flow ratio at 3.2x – meaning it will have $3.20 in debt for every dollar in cash flow it generates. Analysts say Cenovus needs oil prices to remain at least as high as they are now in order to fund its quarterly dividend – even with the current payout of five cents per share being nearly 82 per cent lower than it was two years ago.

Dan Tsubouchi, chief market strategist at Stream Asset Management, argues those concerns should take a beat seat to the benefits of the ongoing Canadian oil sands consolidation being led, mostly, by Canadians.

“The supermajors like ExxonMobil and Chevron are all emphasizing the [Texas] Permian basin as their priority, whereas these are ‘THE’ core assets for Cenovus and Suncor,” Tsubouchi told BNN via email. “If any company will try and grow SAGD [the most common method of oil sands extraction], it will be Cenovus and Suncor and not the supermajors.”

“This is a positive for Canada’s oil sands,” Tsubouchi said.

Recent pipeline approvals help to bolster the positive outlook maintained by both Tims and Tsubouchi. Beyond Kinder Morgan winning approval to nearly triple capacity of its Trans Mountain pipeline to the British Columbia coast and Enbridge undertaking a multibillion-dollar expansion of its already-massive two-million-barrel-per-day export network, there is the recent approval of Keystone XL to consider. After being left for dead by former U.S. President Barack Obama, the controversial pipeline got the green light from Washington on March 24.

Taken together, these new export conduits will help ensure the discount Canadian oil sands producers are forced to take – in part because it costs more to process oil sands bitumen but also because of a persistent lack of pipeline capacity – will remain minimal for the foreseeable future. Keystone XL in particular will help ensure consistent demand for heavy Canadian oil sands crude, as that is what American refineries in the Gulf Coast region are mostly designed to process and their current main sources of supply – Mexico and Venezuela – are declining for political (but also basic geological) reasons.

Tsubouchi argues all those factors create the “best chance for growth in the oil sands [and] that means the best scenario for growth in oil sands capital spending and therefore of people directly in the oil sands.”

Multiple risks, however, remain. Just to name a few as far as oil sands growth and job creation are concerned: The United States could impose a border adjustment tax on imports of Canadian crude – killing the incentive for U.S. refiners to buy oil sands bitumen. The OPEC cartel could end its production cutbacks and send global prices plummeting yet again. American refiners could simply retool to take better advantage of the massive surge in domestic U.S. shale output. And recently-approved pipelines could land in legal limbo.

“We are witnessing a very major change in the Canadian oil and gas industry,” said Matco’s Tims. “It has many dimensions.”