Dec 8, 2021

Merkel Has Earned Her Place in History for Better and for Worse

, Bloomberg News

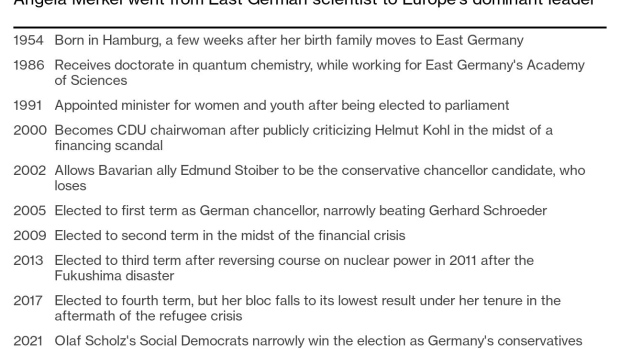

(Bloomberg) -- Few thought that the young woman from East Germany who Helmut Kohl dismissively called his “girl” in the 1990s would go far. And yet after 16 years and 16 days Angela Merkel exits the stage just shy of his record as the country’s longest-serving chancellor since World War II.

While her former mentor — whom she famously and opportunistically brushed aside — will be forever known as the father of reunification, the scientist who went on to become the nation’s “Mutti” (German for mom) leaves behind a more complicated legacy.

She fell short in bringing about the transformative change Germany needs for the challenges it now faces. The economic powerhouse she inherited has fallen behind in technology, failed to anticipate the threat China would pose to its manufacturers or the need to wean its renown carmakers off diesel sooner. Her track record during the pandemic is mixed.

Still, Merkel is one of a handful of living leaders whose influence merits its own “ism.” Fans would say Merkelism is pragmatic statecraft and a dogged determination to bridge differences — “square the circle” as Merkel might put it. Critics would call it a lack of vision, a byword for dithering (“merkeln”).Read more: Germany Stuck With Merkel’s Unfinished Business

Both can be right. Her consensus-building and kicking-the-can-down-the-road skills were never on better display than in 2010, when she bailed out Greece at the 11th hour to save the euro. When Donald Trump entered the White House in 2016, her single goal was simply to hold things together with a dangerously disruptive president who openly goaded her.

And while much of her politics came across as transactional, there were moments where she took a moral stand and held firm, from her decision to proceed with the phaseout nuclear power after the 2011 Fukushima disaster to refusing to close German borders to Syrian refugees in 2015.

Subtly charming and reserved, Merkel rose from a sheltered childhood as a pastor’s daughter in communist East Germany. She entered politics as a 35-year-old rookie after her career as a quantum chemist vanished following the fall of the Berlin Wall.

It’s notable that she initially looked to join the center-left Social Democrats before swinging to a party later absorbed by Kohl’s conservative Christian Democrats. Her unideological approach to politics was a trademark even then.

After winning her constituency on Germany’s gritty Baltic coast, she jumped straight into Kohl’s first post-reunification cabinet, albeit with a rather marginal post. As an unassuming woman from the poorer east she flew under the radar, outlasting more experienced alpha male rivals and honing the kind of survival skills that became a hallmark of her political career.

Alongside her fluent Russian and affinity for eastern Europe, her upbringing in a communist police state contributed to an ability to bite her tongue and bide her time. With Kohl weakened by a party financing scandal, she seized her moment and publicly broke with him, writing in an opinion piece that it was time for the CDU to move on without its “old warhorse.”

She voiced what many in the party base were thinking at the time but few dared to utter. The move put her in position to succeed Kohl. Even then, no one expected her to last.

In 2002, conservative grandees were against her running for chancellor, backing instead Edmund Stoiber, the head of the Bavarian sister party. Shortly before a public showdown, she conceded to him over breakfast. The incident was indicative of Merkel’s ability to read a situation and come out with her reputation intact. Stoiber then narrowly lost the vote to Gerhard Schroeder, making Merkel the next conservative candidate.

As chancellor, she started tentatively, emerging as a global figure in the course of the global financial crisis and learned the lesson of getting too close to other power players. In April 2008, she invited Josef Ackermann, then chief executive officer of German financial giant Deutsche Bank AG, to celebrate his 60th birthday with several dozen guests in the Chancellery in Berlin, a rare opening of her inner sanctum. A few months later, the banker mentioned the illustrious party in a talk show. Her office was eventually forced to admit the dinner had happened.

With the broken financial system roiling the economy, the image of cozy relations with the banker reeked of impropriety. She was furious in her quiet, behind-the-scenes way and ultimately cut ties with Ackermann. While she often took executives on state visits, they were kept at arm’s length.

Her upbringing behind the Iron Curtain also contributed to a certain fascination with the U.S. One of her most treasured relationships, perhaps surprisingly, was with George W. Bush — the first of four presidents she worked with. A deeply unpopular figure in Germany after the Iraq War, Bush invited Merkel to his ranch in 2007, giving her the full Texas treatment complete with cattle, horses and pickup trucks. Even years later, she confided to those close to her that she longed to go back.

Merkel’s relations with Barack Obama were more complex. While she admired his oratorical skills, she saw him as less of a doer and thwarted a request to give a campaign speech in front of Brandenburg Gate. The two gradually grew closer, and he played a role in convincing her to run for a fourth term in 2017 as Trump took power and Brexit and right-wing populism shook Europe.

As for Trump, she tried hard to understand him, but eventually gave up. In 2019, after a bilateral meeting at the Group of 20 summit in Osaka, Japan, Merkel left visibly frustrated by his inattentiveness. “I could have also spoken to a flagpole,” she confided to an official.

Though she has kept dialog open with Vladimir Putin — a former KGB station chief in East Germany — their interactions were laced with Cold War-era intrigue. During her first visit to the Kremlin in 2002, when she was still opposition leader, Merkel and Putin stared at each other for minutes. Eventually, Putin broke the silence by greeting her in German. She responded in Russian.

During a meeting in the Black Sea resort town of Sochi in 2007, Putin tried another mind game, letting his black Labrador into the room, knowing full well she has a fear of dogs. While Merkel often appeared formal in public, she had a humorous side and could laugh about herself. In private, the chancellor loved to tell jokes about fellow leaders she could imitate with comic precision.

Read more: Merkel Reveals What She’ll Do After Her Chancellorship: Nothing

As her era closes and she has time to tend her potato patch, wander through South Tyrol’s mountains and take a longed-for cross-country road trip in the U.S. with Bruce Springsteen playing on the radio, it’s clear there won’t be another leader quite like Merkel.

That might be a good thing, and force Germany to face the problems that Mutti had ably swept under the carpet.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.