Aug 10, 2022

Mexico’s Shadow Banks Collapse, Wiping Out Foreign Bondholders

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- Sergio Camacho, the chief executive of Unifin Financiera SAB de CV, was sick of the questions about the financial health of his firm, the largest shadow lender in Mexico, and he was out of patience.

Unifin was doing well, he blurted out, and would grow its business and thrive. “The market has been irrational,” Camacho barked at one investor after cutting him off during the firm’s earnings call last month. “No matter what I do, they are not reacting to the fundamentals of the company.”

Just 17 days later, the equipment-leasing firm halted payments on its $2.4 billion in foreign bonds and told creditors it would initiate talks to restructure the terms of the debt. And in so doing, it unmasked the greatest of all the miscalculations and false hopes in the crisis that has ravaged the Mexican shadow lending business: That the troubles that arose a year ago at one firm, and then shortly thereafter at another, were contained and did not spell doom for the other dominant players in the industry.

The decision shocked investors and analysts who’d been allayed by reassurances from Unifin’s management and solid financial numbers, at least compared to other problematic non-bank lenders.

“To put it mildly, we are flabbergasted and feel blindsided” by Unifin, said Rafael Elias, the managing director of Latin American corporate-credit strategy at Banctrust & Co. in New York. “We asked the company specifically why did they think that bond prices were dropping, if there was any particular reason. Management told us that ‘the drop in the bonds is surely related to the general market conditions.’”

Unifin was officially declared in default late on Tuesday by S&P Global Ratings. Meantime, Fitch Ratings slashed the company’s score to C as a “default process has begun,” analysts wrote in a statement Wednesday.

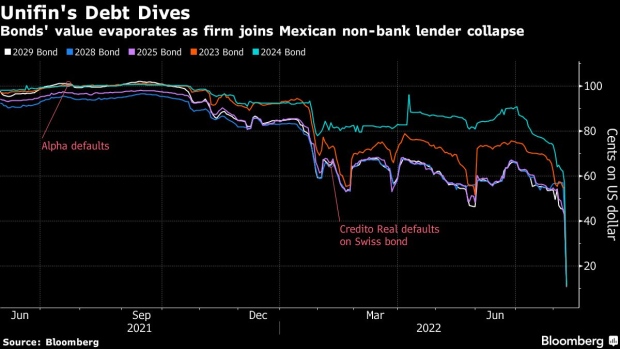

Unifin joins Alpha Holding SA and Credito Real SAB in a financial collapse that’s all but wiped out a combined $5 billion of bonds. Any number of problems got the firms, and their bondholders, in trouble: Both Alpha and Credito Real scared investors by disclosing accounting problems. But in the end, the collapse was hastened by a sudden surge in interest rates in Mexico and the US, which further cut off the firms from the easy-money they depended on.

“This may turn investors completely off the industry,” said Omar Zeolla, an analyst at Oppenheimer & Co. “Until now, we thought that Alpha and Credito Real were unique occurrences. But Unifin’s announcement makes this more of an industry issue.”

Credito Real defaulted on a Swiss franc bond in February, less than a year after doubts about the sector surfaced with Alpha Holding’s disclosure of a $200 million accounting error. Credito Real followed with a revelation of its own -- that non-performing loans were about 82% higher than disclosed in an earlier filing. But no such revision has been reported by Unifin, which leases equipment to small- and medium-sized businesses.

Unifin’s unexpected default spurred an epic nosedive in its bonds and shares, with dollar notes due in 2023 plunging by 44 cents to just 11 cents and its Mexican shares falling 89% on Tuesday. The assets lingered near all-time lows on Wednesday -- not far off from the damage in Credito Real and Alpha’s notes, which are now worth pennies on the dollar.

The default prompted Bank of America to cut its rating of all Mexican non-bank financial institutions -- including Operadora de Servicios Mega SA, Financiera Independencia SAB, Mexarrend SAPI and Credivalores-Crediservicios SAS -- to “underweight.”

Natalia Corfield, JPMorgan Chase & Co.’s head of Latin America corporate credit research, said in a Tuesday note that Unifin’s move may be tied to a potential inability to roll over debt -- or else very strict conditions to do so. There may have also been a realization by company management that its business was unsustainable under the current capital structure, or there might have been accounting issues, she wrote.

An external representative for the company said its decision to stop paying its debts came following last-minute financing plans were canceled after lenders demanded payment of revolving lines.

There’d been several reasons to have more faith in Unifin’s commitment and ability to repay bondholders. Aside from its insistence that it shouldn’t be blamed for the sins of its peers, it also made strategic moves -- from agreeing to a $500 million credit line with Credit Suisse Group AG and finalized an accord to extend the maturity of its 2022 unsecured bond to May 2024. The Unifin representative said the company had only used $300 million from Credit Suisse and decided not to take the other $200 million.

Existing Risks

But the risks were also there. The company’s dollar bonds have been in focus since its peers brought doubt into the market in mid-2021, beginning to slide in earnest as Credito Real neared a default.

“The company’s inability to tap international debt markets is an existential threat to its business model,” said Gilberto Garcia, an analyst at Barclays Plc, which halted coverage of the company on Wednesday. “While there was an element of sector contagion impacting the company, there are also company-specific issues that have weighed on Unifin.”

The sagas of Credito Real and Alpha are also far from over. Both are embroiled in bankruptcy proceedings, with Credito Real on Tuesday announcing that it had “successfully negotiated” the liquidation of its liabilities with some creditors. The company on Tuesday also made its first US bankruptcy court appearance in Delaware.

Credito Real’s former CEO, who stepped down from the role last year, pushed the company into liquidation last month, setting the stage for a legal brawl over the best way to repay creditors owed $2.5 billion.

Alpha’s bankruptcy proceedings have been largely stalled as it seeks a remedy in Mexico.

The three companies had been market darlings, offering bond buyers lucrative yields while cutting small loans -- and charging double-digit interest rates -- to the millions of traditionally unbanked across Mexico. Unifin, though, is the largest of the bunch. That’s left investors to sort through the rubble for clues about the future of the industry.

“The company is either trying to be opportunistic with this drastic and dramatic action or the situation is worse than bond holders were led to believe,” said Oren Barack, managing director of fixed income at New York-based AGP Alliance Global Partners. “It will be a while before a Mexican non-bank bank will be able to return to debt markets. In these uncertain times, that can be the one area of certainty.”

(Updates with Fitch downgrade in sixth paragraph)

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.