Jan 4, 2022

Millennials are finally spending like grown-ups

, Bloomberg News

Millennials are growing up. After spending years splashing out on everything from skydiving excursions to Instagrammable vacations in Peru, 30-somethings with decent-paying jobs are making lasting purchases, buying cars, houses and everything inside them. The retreat from offices during the pandemic has only cemented the urge to settle down and accumulate the trappings of adulthood.

While COVID-era disruptions have been the primary trigger of the rapid price increases in consumer goods, a long-delayed, demographics-driven shift in spending is also underway, one that could help fuel inflation long after the supply-chain wrinkles are ironed out and the pandemic subsides.

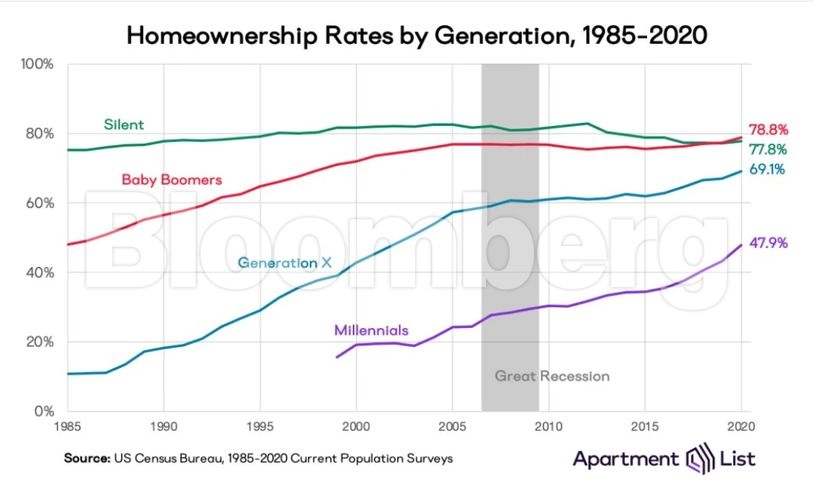

Consider the untapped capacity for spending. After the global financial crisis, millennials saddled with student debt famously moved into their parents’ basements, pushed off marriage and delayed having children, if they decided to have them at all. Just 47.9 per cent of U.S. millennials — the 72 million people born between 1981 and 1996 — owned homes in 2020, according to Apartment List analysis of census data. At age 35, millennial home ownership hit 53 per cent compared with 60 per cent for Gen Xers and baby boomers, and almost 70 per cent for pre-boomers.

For many, marriage and kids came eventually. But the pandemic was a watershed moment. Millennials flush with savings or simply desperate for space finally started making long-term acquisitions. Last year, the cohort accounted for more than half of home-purchase loan applications and bought more new cars than any other age group.

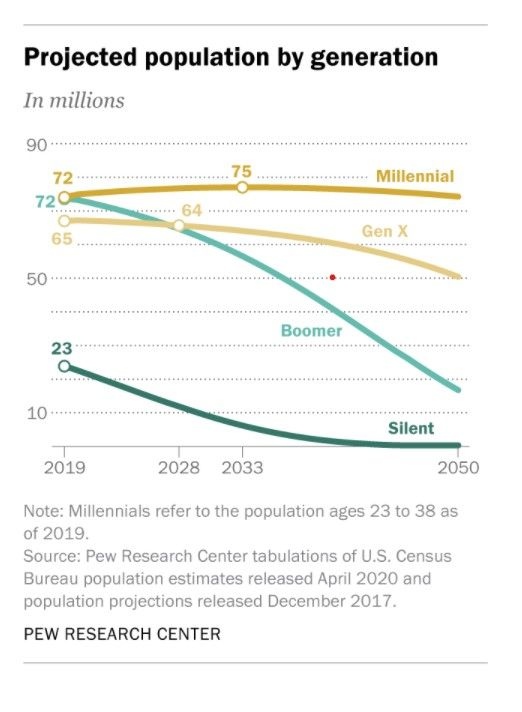

The key factor that could affect inflation isn’t just demand but the size of the millennial population, which outpaced baby boomers in 2019 to become the largest U.S. generation. For years, the dominant macroeconomic themes have been deflationary: aging, fewer babies and automation. Those forces aren’t going away, but we could see a multiyear spurt of spending driven by millennials.

Indeed, the consumer categories with the fastest pace of price increases in November included big-ticket items like new vehicles (11.1 per cent) and used cars and trucks (31.4 per cent), while shelter rose 3.9 per cent. In 2019, millennials put a larger share of their total spending toward housing and transportation than older generations.

The cost of major expenditures is rising outside the U.S., too. In China, a surge in property prices is particularly worrying to the government, whose “common prosperity” doctrine aims to close income-inequality gaps. In Singapore, millennials’ frustration over high housing prices could become an election issue, while anger over high housing costs has become a hot-button topic in countries from Germany and Canada to South Korea and Australia.

One question may be whether millennials really have more money to spend, or whether they simply feel wealthier after two years of spectacular paper gains. “People who have money feel wealthy even though it’s not realized wealth,” said Dan Ariely, a professor of psychology and behavioral economics at Duke University. “That’s adding to the willingness to spend on all kinds of things.”

Millennials’ spending spree won’t last forever. In a decade, when the first wave turns 50, increased savings will help push interest rates lower, said Linda Nazareth, an economist and host of the podcast “Work and the Future.” By that point, the oldest Gen Zers will be in their prime homebuying years. Given the severity of the COVID downturn, their entry into financial adulthood could be just as delayed as the generation before them.