May 26, 2021

MoneyTalk: Can I help my kid with their first mortgage?

Presented by:

Getting into the house market these days is hard. Here are four ways parents can help their adult children and some things to think about before they hand the money over.

Home-buying math can be hard for parents and their adult children and can lead to some difficult discussions across the kitchen table. For many Canadians, no matter how you crunch the numbers, it’s tough to buy your first home.

Fortunately, mom and dad may have the key to helping out their kids, through their savings or their own home equity. Without that financial boost from them, owning a home could be out of reach for many.

If you’ve been thinking about how to help your kids in this situation, you’ve probably done the calculations. The average home price in Canada, as of March 2021, was more than $600,000, higher in Canada’s urban areas.1 First-time homebuyers must come up with a 5% minimum for the first $500,00, plus 10% on the portion of the purchase price above that, which works out to an average down payment of $35,000. However, in Canada’s largest urban centres, where house prices are higher and markets more competitive, it’s not uncommon for first-time homebuyers to be on-the-hook for down payments of up to $50,000.

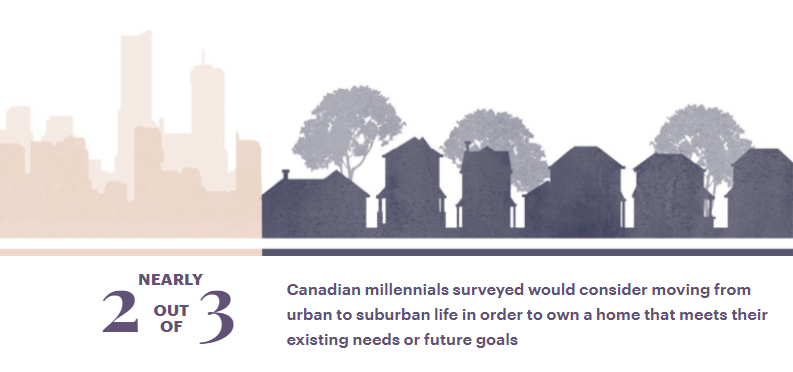

At such prices, even millennials with established careers and great educations may find the door to the housing market locked and bolted. Government agencies have provided programs to help the young get into the market, including the Home Buyers Plan, which allows RRSP holders to borrow from their savings for a down payment. However, constantly rising house prices seem to outstrip the effectiveness of these efforts.

Unfortunately, these programs won’t stop young adults turning to their parents for help, says Laima Alberings, Tax and Estate Planner at TD Wealth.

Helping your kids enter the home market is one way you can give them a financial leg up in an increasingly expensive world. But how parents give kids money for homes could be as important as how much they give, says Alberings. You want to choose a method that makes sense for you and doesn’t endanger your own financial future. Once the decision is made to give funds to your kids — a decision both parents and kids must ponder carefully — parents must navigate a bundle of ownership, legal, financial, and even relationship issues.

For instance, one top-of-mind question for parents is, how can you protect the $50,000 they are thinking of passing over the kitchen table from becoming part of a divorce settlement or being lost to creditors? According to family law legislation in various provinces, the equity of a family home is generally divided between spouses in case of a marital breakdown. If the son or daughter is in a relationship, mom and dad may want to hope for the best when transferring money but plan for the worst possible outcome.

Here are four options parents can consider before picking up the cheque book.

1. A loan from the bank of Mom and Dad

Typically, a “loan” could be as simple as an informal agreement mulled over the kitchen table where payback expectations may be discussed but there’s no paperwork. Alberings cautions that family members should be wary about these forms of loans even when they have the best family relations because, if it is not legally documented, it may not be regarded as loan in a court no matter what promises were made in the kitchen.

The benefits of having a documented, secured loan is that everyone is aware of what is expected. The loan can protect your contribution money in the case of a marital breakdown or if your child has creditors, but it may also raise some uncomfortable questions about what to do if your kid defaults on the repayment.

Parents who wish to draw up a loan for their children should get advice from a lawyer. Their loan contract should include details on the interest rate, the schedule of interest payments and the payback date. It should also be secured against the property, says Alberings. However, if you don’t honestly expect the money to be paid back or deliberately want the terms to be vague, it may be best to call the money what it is — a gift.

2. A gift, with or without strings attached

The most informal method of transferring money to your kid is a simple gift. Money can be given over with no strings attached but the lack of any legal structure over the handover of funds can create complications. Once money is given to a child, a parent loses control over the funds. They can’t ask for the money back or suddenly create retroactive conditions, says Alberings.

Depending on the relationship between the parents and their child, this may be fine. But if there is an understanding that the funds should be used a certain way — for example, to pay for a semi-detached home, not a condo and a trip to Europe — the relationship may become damaged. As well, gift money that is used to purchase a home is not easily protected from marital breakdown, even if it’s a formal gift that is documented in a Deed of Gift.

3. A guarantor or a co-signer to the mortgage

If a child has a poor credit history or doesn’t have the funds for a down payment, a parent can volunteer to be a guarantor to the mortgage or co-signer to the property. What’s the difference? A guarantor guarantees payment of the mortgage while a co-signer’s name goes on the title of the property and they become a co-owner.

But Alberings says that while helping out a kid this way may get them into their first home, risks and responsibilities are now shared with the parent. For instance, if the child were to default on their mortgage, the co-signer or the guarantor would be required to make mortgage payments and legal action could be brought against the parent.

But a much more practical problem is that a parent who legally commits to their child’s home purchase may find themselves financially overextended, says Alberings. Should mom and dad wish to make a large purchase or require a loan of their own in the future, they could be seen as a risk in the eyes of a financial institution and be turned down.

4. Set up a discretionary trust

This option may be helpful, firstly, if people have the means to own additional properties and secondly, if the parents are concerned the house may be at risk because of their child’s creditors or due to a potential breakdown in marriage. The benefits of using a trust to purchase a home are that the trustees (the parents) get to keep complete control over the property and don’t have to transfer the property to the beneficiary (the adult child) until they want to. If the trust is set up properly, the parents may decide which beneficiaries shall be able to use the property or to which beneficiary the property shall ultimately be transferred.

Alberings says that while there is a tax advantage to using a trust compared to the parents owning this property personally, this option may be costly and isn’t for everyone. In addition, it does not improve the credit-worthiness of the child the way a traditional mortgage would, and it prevents the principal residence exemption from being used while the property is held in the trust. A discretionary trust may not get your child a first mortgage, but it does get your child a home.

Think carefully before committing

Ultimately, while helping kids out financially may seem like a natural extension of the care and support parents have always given, the risks involved with parting with large sums of money should always give people pause, says Alberings. She says parents should also consider balancing the wishes and dreams of one kid versus their other children. Can they afford to help two kids out with mortgages? How might they weigh a down payment for one child against start-up money for another child’s new business?

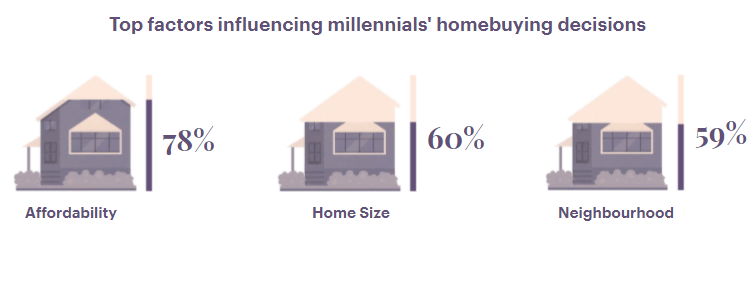

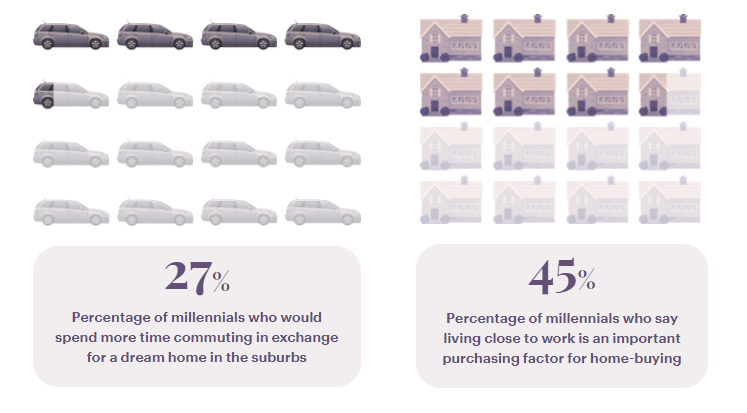

Alberings reminds people that in many areas, the affordability of the housing market has changed abruptly in a short period of time. Buying property was once accessible to many people who were employed full-time. Now, she says, many markets are such that everyone — parents and their home-buying children — must adjust their expectations of what is affordable and possible, and not according to any white-picket-fence dreams. These days, a great first home might come with a long commute or simply be a smaller unit in a new condo development. Helping a child buy a home comes with financial and legal risks that everyone must be aware of no matter how well-intentioned parents and their kids are. A planner or financial advisor can help establish financial priorities and estimate how much home can be purchased and the best way to do it with a parent’s help.

About the survey: TD Bank Group commissioned the TD Spring Homebuying Survey which included 761 millennials, aged 25-34, from across the country, between February 22 and March 4, 2019.↩