Dec 12, 2018

MoneyTalk: Grandparents and RESPs - Hope (and help) for the future

Presented by:

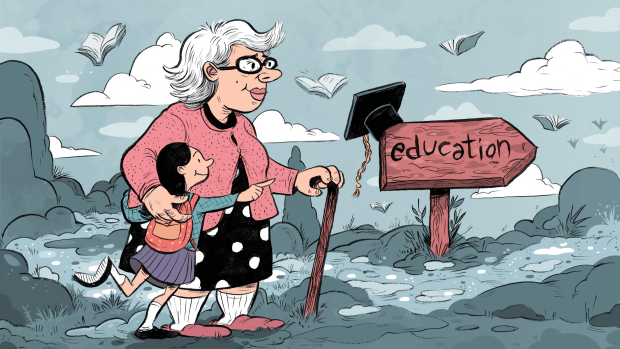

Grandparents naturally want to help their grandchildren get a good education; is opening a separate RESP really the best option?

A new child in the family is a joyful time but also a period of hopes, plans and reflections. Grandparents, a step removed from immediate new-baby chaos and lack of sleep, may consider a thoughtful contribution to the household during the celebrations, the gift of higher education.

It's a consideration as important as any other large financial goal. Statistics Canada reports that the average tuition for full-time students in 2017-18 was $6,571 with living expenses on top of that. One estimate is that, for children attending university in 2036, the cost of four years in school could top $138,400. What if they wish to pursue law or medicine?

With this in mind, the more enthusiastic grandparents, days after birth, often march into their bank, the infant’s freshly issued SIN in hand, to open a Registered Education Savings Plan (RESP).

RESPs are the go-to savings plan for parents saving for their child’s education, as they provide a means for accessing government grants and may allow investment income or gains to accumulate on a tax-deferred basis. Starting early allows a plan to maximize the potential for compound growth — from the time a child is born until the time they cram their gear in the van and drive off to university or college.

$6,571

- Statistics Canada reports that the average tuition for full time students in 2017-18 was $6,571 with living expenses on top of that.

However, while grandparents have the best intentions, should they actually be the ones overseeing a grandchild’s educational savings plan, especially if there is already an existing plan managed by the parents? Are multiple plans per student necessarily better than a single plan?

Ian Lebane, VP, Tax and Estate Planner, TD Wealth, explains that, due to contribution and withdrawal limits and other rules, one plan per student, in some cases, may be easier from an administrative point of view for all concerned. For instance, with an RESP, the federal government’s Canada Education Savings Grant (CESG) provides 20 cents on every dollar contributed up to a maximum of $500 every year for each student up to a lifetime maximum of $7,200. While a student may be the beneficiary of multiple plans, the grants and maximum contribution limits apply on a per student basis.

Therefore, just giving money to the parents of the student for the RESP may eliminate potential difficulties with multiple contributors and coordinating multiple RESP accounts, and also makes the mechanics of withdrawing funds more efficient.

Having parallel plans in place for one child can run the risk of not contributing enough. The individual who enters into an RESP contract with the financial institution, (usually, but necessarily, a parent of the student) is called the subscriber. Having different subscribers on different plans can give rise to coordination issues that could prevent a child from getting the full benefits from the grant if not enough money is contributed in any given year. As well, there could be over-contribution problems if the subscribers don’t co-ordinate. The lifetime limit for contributions is $50,000 and a tax (1% per month) will be imposed on contributions above the maximum on the subscriber.

While sometimes our kitchen tables act as accountants’ offices, synchronizing contributions from various grandparents, parents, and perhaps others, may be a job in itself.

Lebane also makes the point that, if the grandchild decides not to pursue post-secondary education or decides not to finish a degree after a few years of study, there may be adverse tax consequences for the grandparent as a subscriber upon withdrawing any growth earned within the plan.

Starting early allows a plan to maximize the potential for compound growth — from the time a child is born until the time they cram their gear in the van and drive off to university or college.

Any income growth (or investment gains) generated on invested funds may face an additional 20% penalty, (in addition to being regarded as income) if it is withdrawn by the subscriber instead of being used by the beneficiary for education purposes. The grant money that has been accumulating, but not paid to the child for education purposes, can’t be withdrawn by the subscriber; any grant funds remaining in the account must be repaid to the government if the account is being closed.

These restrictions and penalties apply to any RESP subscriber, not just grandparents. If a subscriber withdraws accumulated income from the RESP, they could potentially defer tax by rolling the funds into their own RSP. Since grandparents have likely been saving for retirement for a longer period of time, they may have already used up all their RSP contribution room, whereas a parent may have more flexibility to effect this rollover.

Even if a student leaves a program without completing it, the subscriber may choose to leave the funds in the plan since RESPs can stay open for 35 years, and the student could still decide to return to school at some point.

Lebane says that another consideration is that grandparents may pass away during the life of the RESP plan before the child starts university or college. This may create a problem if the RESP is not addressed appropriately in the deceased grandparent’s will. In certain circumstances, the funds may become subject to the provincial probate tax and be regarded as part of the larger estate.

If grandparents (and parents) are concerned about how the RESP would be treated in conjunction with their will, they should consult their lawyer or financial advisor about naming a successor subscriber.

Just giving money to the parents of the student for the RESP may eliminate potential difficulties with multiple contributors and coordinating multiple RESP accounts.

While grandparents may be enthusiastic about contributing to education when a child is first born, managing RESPs is not a sprint but a marathon. To receive the full benefit of grant money available, people should contribute the maximum amount to receive the full federal grant every single year until the $7,200 grant lifetime maximum has been reached.

And not surprisingly, sometimes a grandparent’s zeal can wane, particularly if the number of grandchildren with RESPs grows from one to two to many more over the years.

It’s because of these potential complications that Lebane believes that an alternative course of action may be for grandparents to make a gift of money to the parents and let the parents act as the subscribers to the plan. In this way, coordination issues and complications described above may be avoided. In fact, if the funds within the plan are actively invested and the grandparent has more investment experience than the parent, the grandparent could be appointed under a Power of Attorney or granted trading authority to manage the investment aspects of the plan although the parents remain the subscribers.

Grandparents may be worried they may lose control of the money reserved for their grandchild’s education if they simply hand it over to a parent. This could be a concern if their adult child is divorced and resides with a son or daughter-in-law who may be estranged from the grandparent. If the grandparent has the account number of the plan and written permission from the subscriber (the parent), they can make a contribution directly to the plan.

Lebane emphasizes that everyone — not just grandparents — who open RESP accounts should address the RESPs appropriately in their wills. Everyone’s situation is different and Lebane adds if you need help sorting out how you should manage your RESP, the expenses, and what make sense for your family situation, check in with your financial planner, investment advisor or lawyer and see what they can suggest.