Oct 7, 2022

Mongolia’s Central Bank Says Debt Management Is ‘No. 1 Task’

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- Mongolia’s central bank governor said keeping debt under control is the main focus right now amid a worsening foreign currency crunch as reserves slide.

“2023 is the most stressful year related to the government’s debt,” Governor Lkhagvasuren Byadran told lawmakers on Thursday. “Debt management in 2023 seems to be the No. 1 task to be done.”

Foreign currency reserves of $2.8 billion were not at a “level of danger,” he said, adding that reserves had increased in September for the first time this year. The government could move to pay down some of its debt if reserves continue to increase, he said.

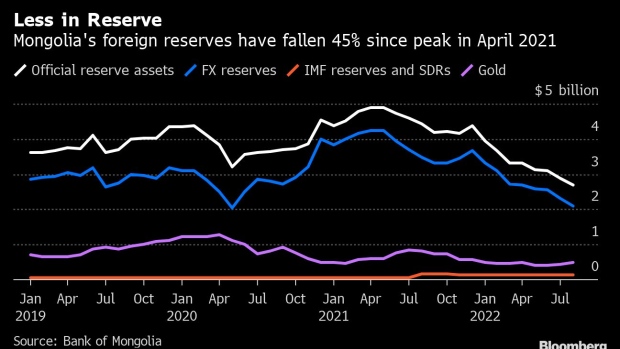

Mongolia’s foreign currency problems are worsening after reserves plunged 45% since its peak in April last year. Khan Bank, the nation’s biggest lender began restricting the amount of foreign currency customers can buy in September, citing “liquidity issues.” Other commercial banks have done the same, according to multiple customers.

Khan Bank said exceptions were made for customers including corporate and small-medium business clients, and that as of Oct. 5, its liquidity ratio on foreign currency was nearly triple what’s required by the Bank of Mogolia.

The currency crunch stems from Mongolia’s current account deficit, the broadest measure of trade in goods and services, which ballooned this year as exports slumped and surging energy prices boosted import costs. Mongolia’s shipments to neighboring China, its biggest trading partner, have been severely disrupted by Beijing’s Covid Zero controls.

The current account deficit was $2.4 billion in the first eight months of the year, 43% bigger than the same period in 2021.

Lkhagvasuren said the country needs to boost its exports to ease pressure on its current account. Reducing transportation costs by eliminating bottlenecks at the border would help alleviate exchange rate pressures and price rises, he said.

Mongolia’s public debt amounted to 70% of gross domestic product, the central bank said in a June report. The World Bank estimates that the overall debt ratio, including off-budget items, amounted to 92% for the full year in 2021.

George Xu, associate director of Asia-Pacific sovereign ratings at Fitch Ratings Ltd., said state-owned companies pose “contingent liability risks to Mongolia’s public finances given large number of SOEs are loss-making.”

He highlighted several drivers that could warrant a negative rating action: failure to reduce the budget deficit or stabilize the government debt-to-GDP ratio, or a “crystallization of large contingent liabilities on the sovereign’s balance sheet.”

The currency, the tugrik, has lost about 15% of its value against the dollar this year, with surging US interest rates helping to drive it weaker. The Bank of Mongolia recently raised interest rates to 12%, which the governor said was to “maintain stability” in the economy.

Mongolia’s sovereign bond due in December is on track to lose 2.9 cents on the dollar this week, matching last week’s losses which were the largest weekly declines since March 2020, according to Bloomberg-compiled prices. But the bond is still trading at 94 cents, suggesting investors are pricing in a low likelihood of default for the near-term payment.

Lkhagvasuren said the swing in prices for bonds would likely be temporary.

(Updates with comment from Khan Bank in fifth paragraph)

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.