Sep 30, 2022

Mongolian Banks Curb Dollar Flows to Fight Worsening Cash Crunch

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- Mongolia is facing a worsening foreign currency crunch following Russia’s war with Ukraine and a slump in China’s economy, forcing local banks to restrict the amount of dollars customers can buy.

Khan Bank, the country’s largest bank measured by total assets, limited the daily amount of cash that can be converted into foreign currencies to 1 million tugrik ($300) from this month, Vice President of Wholesale Banking Uuganbayar Terbish said in an interview on Thursday. That’s down from as much as 300 million tugrik under normal banking conditions and 100 million tugrik in June, he said.

Multiple bank customers who’ve tried to transfer funds at four different commercial banks in recent weeks confirmed they were limited to a daily foreign exchange amount of 1 million tugrik.

“These are not capital controls, but market liquidity issues,” said Uuganbayar, adding that the restrictions were a response to the increased demand for dollars and to guard against speculation. He said the bank wasn’t limiting payments for the import of goods such as food and fuel, and exceptions could be made with approval from the treasury department.

Golomt Bank, Xacbank and Trade and Development Bank of Mongolia didn’t respond to requests for comment.

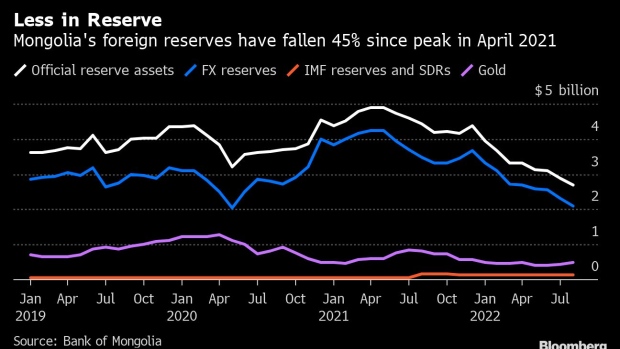

Mongolia is facing an increasingly serious foreign currency crunch, with foreign exchange reserves down 40% in August from a year earlier to $2.7 billion and the current account deficit ballooning. In addition, the tugrik has taken a beating due to interest rate hikes overseas, losing 16% of its value against the dollar this year. The central bank has repeatedly hiked interest rates this year in an attempt to rein in high inflation and curb the currency outflows.

The nation’s economic problems stem in part from its two huge neighbors: Russia and China. Beijing’s Covid Zero policies have disrupted trade across the border, while the war in Ukraine has not only driven up the price of imported fuel and goods but also blocked access to some Russian banks, which had been an important part of the nation’s financial system.

The situation is somewhat reminiscent of the crisis in 2016, when a slump in global commodity markets forced Mongolian banks to ration foreign currency and the country eventually had to ask the International Monetary Fund for a bailout.

“There’s always risk” of the country needing another bailout from the IMF, according to Adrienne Lui, an economist at Citigroup Inc. in Hong Kong, although there are many more positives now. Commodity prices are still high, and the government is stable, she said.

While Lui said she didn’t think the situation in Mongolia was comparable to the crises in Pakistan or Sri Lanka, the tugrik’s “depreciation will continue as long as balance of payments stress remains,” she said.

The Asian Development Bank approved a $100 million emergency loan for the country in August to “help it weather the impacts of severe economic shocks.” The Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank on September 29 approved another $100 million financing in cooperation with the ADB in a program to assist government financing, provide aid to the vulnerable, and counteract imported inflationary pressures.

Dollar bonds issued by Mongolia and due in 2023 and 2024 fell about 4 cents Friday, according to prices compiled by Bloomberg, on pace for their biggest declines since March 2020. The tugrik also weakened and was trading at 3,337.7 to the dollar at 4:30 local time.

Rising costs combined with stagnant wages drove young people to protest outside the parliament house in April, although inflation has since moderated after hitting a high of 16.1% in June.

Currency Weakens

The central bank hasn’t instructed lenders to restrict foreign currency transactions, according to Tumentsengel Baterdene, a spokesman for the Bank of Mongolia. Pressure on the local currency wasn’t unique to Mongolia, given the turmoil in foreign exchange markets after the US Federal Reserve’s aggressive interest rate hikes, he said.

Risks could rise toward the end of the year when almost $140 million in sovereign debt will mature in early December and need to be repaid, according to data compiled by Bloomberg. That’s followed by more than $1.2 billion in debt which is due next year.

The war has also damaged the country’s access to the international financial system, with sanctions on Russian banks after the invasion of Ukraine disrupting payments and blocking access to the foreign exchange trading platforms they host, according to Javkhlantugs Ganbaatar, the policy and advocacy director at the American Chamber of Commerce in Mongolia.

Current Account Deficit

Mongolia posted a $2.2 billion current account deficit so far this year, partly due to some state-owned companies taking payment for exports before they’d actually shipped out the coal and other goods. This has meant that even as exports have hit records since May in the customs data, there’s little new foreign currency coming into the economy.

In the spring, coal miners accepted early payments to bolster the nation’s foreign currency reserves, Javkhlantugs said. At the time, the central bank governor “spoke of a mass exit of hard currency” following the invasion of Ukraine, and the outflow of foreign currencies over three months exceeded that of the last three years, Javkhlantugs added.

One example of this is state-owned coal producer Erdenes Tavan Tolgoi, which was told by the government in March to pre-sell coal to help finance an almost $400 million oil pipeline development.

Another factor in the deficit is the jump in freight costs due to the war in Ukraine pushing up petrol prices. Most coal is exported via truck and the deficit in transport services jumped to almost $260 million this year due to the increased cost of foreign fuel.

The cost of transport services should return to pre-pandemic levels by the end of the year “with exports regaining momentum owing to easing of border restrictions and imports increasing due to recovery in domestic demand in the recent months”, he added.

Mongolia recently signed a deal with Russia to cap imported fuel prices and a new rail line from coal mines in the Gobi desert to the border with China is expected to expand export volumes and reduce costs.

How long the dearth of foreign currency lasts will depend on the term-length of the coal deliveries paid for up front as well as any further easing of restriction at the border to China. In addition, as well as the rate cuts announced last week, the central bank announced a loosening of the reserve requirements on banks’ foreign-denominated assets, which should free up some their holdings.

The Asian Development Bank this month lowered its growth forecast for Mongolia this year to 1.7% from the 2.3% it saw in April. The World Bank also cut its forecast for growth and noted that Mongolia was one of the nations in Asia most vulnerable to capital outflows and a falling exchange rate due to inflation abroad.

(Corrects 21st paragraph of story published on Sept. 30 to clarify that Bank of Mongolia was referring to the cost of imports of transport services not the overall current account.)

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.