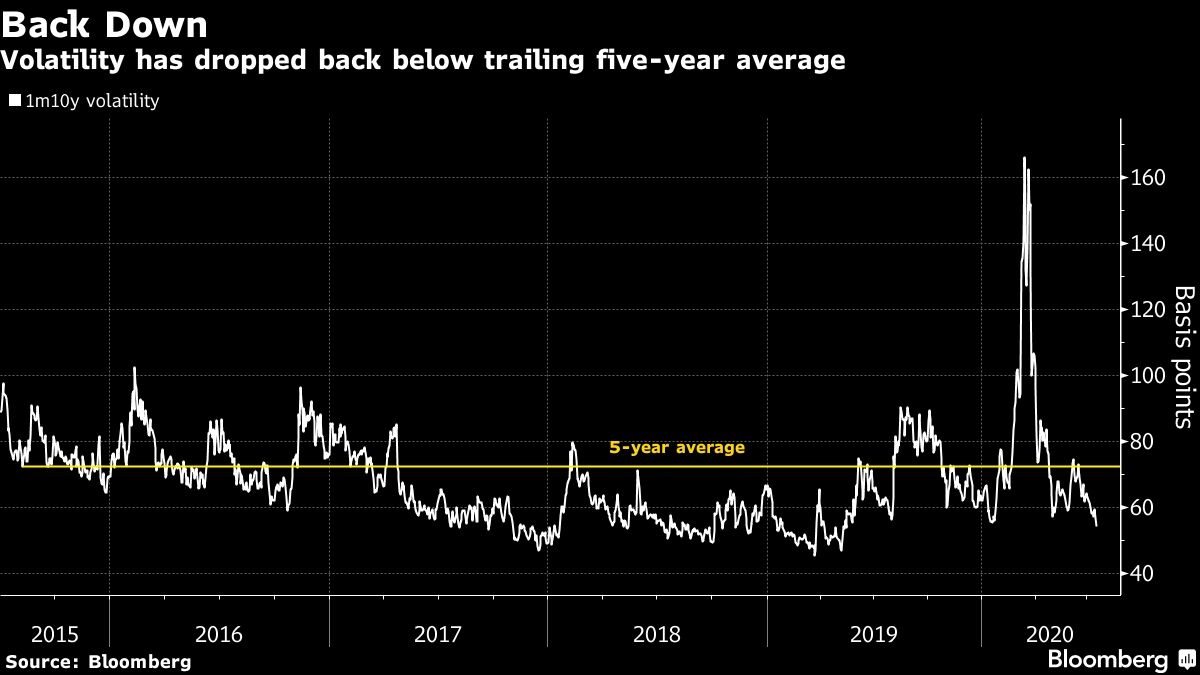

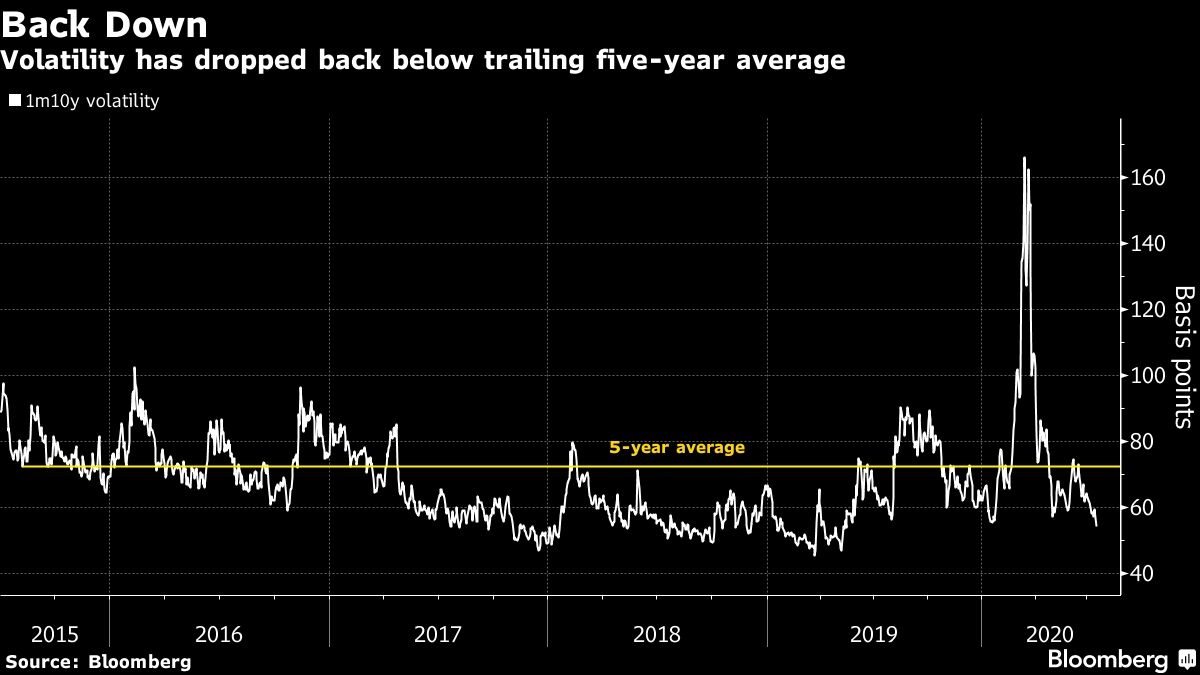

For now, volatility can be scrubbed from the list of worries that keep mortgage-bond investors up at night.

Volatility has plunged 67 per cent from its decade-plus high seen before quantitative easing resumed March 16, and is now well below its trailing five-year average. That benefits MBS investors as the chance of a borrower having an incentive to refinance is in part a function of interest rate volatility over the life of the loan.

Homeowners refinancing mortgages give money back to MBS investors earlier than expected and at par. The higher volatility is, the greater the chance that homeowners are willing and able to do so. And with all 30-year MBS trading above par in the to-be-announced market, this would invariably hurt returns.

Much of the heavy lifting to accomplish this decline was performed by the Federal Reserve via its massive stimulus program that’s seen it purchase US$833 billion mortgage bonds in just the last four months. As with the current round of QE, during the first four months of QE1 (November 2008 to March 2009) and QE3 (September 2012 to January 2013) volatility fell 42 per cent and 20 per cent, respectively, according to data compiled by Bloomberg News.

This low volatility regime may continue to have legs as the central bank looks set to add another US$40 billion per month to its holdings of MBS through year end. If that comes to fruition, mortgage investors may enjoy continued muted volatility.

Christopher Maloney is a market strategist and former portfolio manager who writes for Bloomberg. The observations he makes are his own and are not intended as investment advice