Sep 15, 2021

Mystery of Missing German Inflation Hysteria Hangs Over Election

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- Sign up for the New Economy Daily newsletter, follow us @economics and subscribe to our podcast.

Germany’s sudden spike in pandemic-induced inflation is prompting a noticeably less hysterical response than the country is used to.

Against the backdrop of the most pivotal election in a generation -- bringing the chancellorship of Angela Merkel to a close -- climate-change policies, infrastructure, high rents and taxes are the most significant economic issues. The fastest consumer-price jump since 2008 isn’t so prominent, even though media have highlighted the surge.

That marks a shift from traditional fears of lax southern European-style economics, infused with worries of 1920s Weimar-Republic hyperinflation, that caused alarm during the euro-zone debt crisis in the previous decade, according to academics including Ferdinand Fichtner of Berlin’s University of Applied Sciences.

“It’s surprisingly quiet compared to what you would have expected 10 years ago,” he said. “The outcry could have been louder. As far as the election is concerned, the topic may even be over because there’ll be no new inflation numbers.”

If the less emotive tone persists, it will be a relief for the European Central Bank, which has long been a political football in Germany over its crisis policies and negative interest rates. In 2012, its then chief, Mario Draghi, was given a Prussian helmet by tabloid Bild Zeitung as a reminder of his duty to adhere to the country’s inflation discipline.

In evidence of more sanguine politics, a televised debate on Sunday between candidates vying to replace Merkel after the Sept. 26 vote didn’t even mention inflation specifically. Strike action by railway workers demanding a raise hasn’t featured much rhetoric about rising prices either.

Populist Stance

The populist AfD has also failed to capitalize on attempts to draw attention to inflation, a phenomenon that senior official Alice Weidel described as “the most antisocial form of redistribution.” The party remains in fifth place with support around 11% in opinion polls.

Politicians have cited inflation more after it accelerated to 3.4% in Aug. 30 data. Friedrich Merz, economics spokesman for Merkel’s conservative CDU, warned in a newspaper interview at the weekend of the danger to prices under Social Democrat front-runner Olaf Scholz. Scholz himself said last week that inflation must be monitored closely, though he and the rival Greens have focused more on spiraling rents.

The lack of intensity there reflects citizens’ priorities, not least in the first election for voters born since the advent of the euro. When asked about the biggest problems facing Germany, 43% of respondents cited climate and the environment, 30% the pandemic and only 6% the economic situation, according to a ZDF poll that closed on Sept. 10.

That’s all the more remarkable because media have frequently headlined consumer prices, which are rising faster now than in 2011, when public alarm was pronounced.

“Some newspapers like to campaign against high inflation rates and awaken old spirits, but the discourse has also changed,” said Philipp Heimberger, an economist at the Vienna Institute for International Economic Studies. “The public debate on economic policy and inflation is different.”

People still worry about consumer prices, but not as much as they used to. In a poll finished in July entitled “Fears of the Germans” by insurance company R+V Versicherung AG, 50% were concerned about rising living costs, down from 76% in 2008.

Inflation concerns are understandable, said Peter Bofinger, professor at the University of Wuerzburg and a former member of the country’s council of economic experts. Germans are vulnerable to low interest rates and rising prices because so few are homeowners, he observed.

“If you didn’t buy a house, it can be frustrating to think you missed out, now inflation is accelerating,” Bofinger said. “There’s a rational core to the idea that you have to fear inflation more in Germany than in Spain.”

Heimberger credits the appointment of Isabel Schnabel, one of a new generation of German economists, to the ECB Executive Board since early 2020 as helping change the tone.

It’s “important to offer a factual explanation for the recent price increases and an assessment of future risks, especially in Germany, where many supposed experts and the media are again rousing people’s fears,” she told business people on Monday in the south west. “Persistently excessive inflation, as feared by some, remains highly unlikely.”

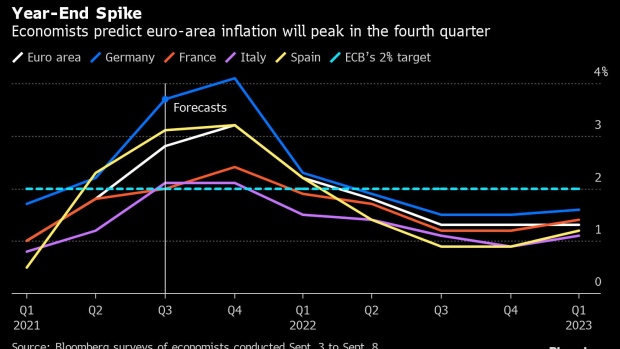

The temperature of debate could still rise. Germany’s Bundesbank reckons inflation may reach as high as 5% later this year. Even sooner, with less than two weeks until the vote, there’s time for consumer-price angst to flare up.

“Before an election, topics tend to get sensationalized,” said Florian Kern, director of Dezernat Zukunft, a Berlin think tank promoting new thinking on economic issues. Still, “I do believe that it’s possible to calm the debate with education.”

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.