Oct 4, 2018

USMCA China clause latest blow to Trudeau's Asia ambitions

, Bloomberg News

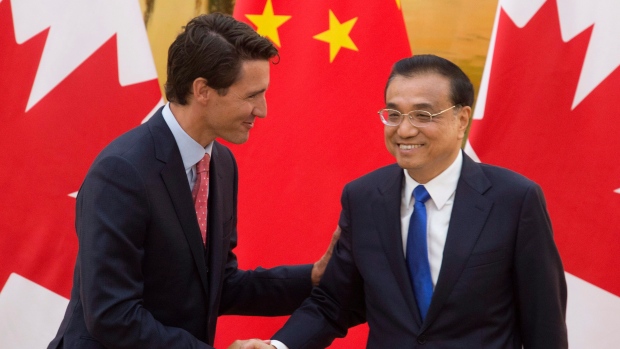

Justin Trudeau dreams of closer Canadian ties with China. The deal he just made with Donald Trump makes it harder for that to happen.

The new trade agreement between the U.S., Canada and Mexico includes a provision that requires one member to notify the others if it launches trade talks with a non-market economy. If those talks lead to a deal, the signatory could potentially be frozen out of the North American pact.

It’s essentially a China clause, with the Trump administration gearing up for trade war with Beijing. It’s also partially symbolic. But for Trudeau, it’s either a concession or an admission that his aspirations for a free-trade deal China have fallen flat.

The Canadian prime minister’s visit to China fizzled last year, and he rejected a major takeover this spring. But in a cabinet shuffle this summer -- when the fate of the North American Free Trade Agreement was still unclear -- he added “diversification” to his new trade minister’s title. And now he’s effectively siding with the U.S. against the Asian powerhouse.

“The U.S. is going to get all its partners to gang up on China, but it’s clear that Canada did this because there was a gun to its head,” said Mary Lovely, an economics professor at Syracuse University who studies trade issues. “Now Canada has its hands tied.”

Article 32.10

The U.S. and Canada reached their deal late Sunday, shortly before a deadline, and published the legal text that would allow it to be signed by the end of November. The U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement, as the new Nafta is known, still needs to be ratified by the U.S. Congress and other legislatures before coming into force.

Article 32.10 requires any USMCA nation to notify the other two members three months before launching free trade talks with a non-market economy. The other countries can review any deal before it’s signed and, once a new pact between a USMCA member and a non-market economy takes effect, the other two members can terminate the trilateral North American agreement and strike a bilateral one.

“They can basically pull the chute and kick you out by virtue of what they feel violates that clause,” said Peter MacKay, who served as foreign minister under Trudeau’s predecessor and is now a partner at law firm Baker & McKenzie LLP. “The government doesn’t seem to be very forthcoming as to why they would want to become supplicant to the United States in a trade war with China.”

Others argue the change is more symbolic. “While I understand why people see this provision as a bit of an infringement on Canadian sovereignty, that’s not typical of an FTA,” said Matthew Kronby, a Toronto-based trade lawyer at Borden Ladner Gervais LLP. “At a practical level, it has far less significance than some people are suggesting it does.”

Both Trudeau and his foreign minister, Chrystia Freeland, have downplayed the significance of the clause. Freeland told reporters in Ottawa Monday that countries are already able to quit the new Nafta, regardless of the China clause.

Trudeau also signaled he’s still interested in wooing Beijing. “China is a significant, growing player on global trade and we as always will look for ways to engage, deepen and improve our trading relationship with them,” he said Tuesday at a press conference in Vancouver.

But the Trump administration is targeting China and views trade negotiations with other nations as a way to set the stage. The U.S. is in talks with the European Union and Japan, and is moving toward a “trade coalition of the willing to confront China,” White House economic adviser Larry Kudlow told the Economic Club of Washington on Thursday.

Lovely, the Syracuse University professor, worries that joining such a coalition undercuts Canadian and Mexican sovereignty on trade issues. “The U.S. is setting itself up as the rule-writer, judge and jury,” she said.

Beyond China

While Article 32.10 doesn’t specifically name China, “they will very much take notice and they will do what they think is pragmatic,” according to Stewart Beck, a former diplomat who now heads the Vancouver-based Asia Pacific Foundation of Canada. The effects of the clause could extend beyond Beijing, he added, potentially preventing Canada from striking a deal with the Association of Southeast Asian Nations, whose members include Vietnam.

Canada probably agreed to the clause -- and other changes in the USMCA -- rather than risk a major rift with the U.S., which is a much bigger trading partner, several observers said. The northern nation exported $411 billion of goods to the U.S. in 2017, according to Statistics Canada, compared with $25 billion to China.

“This was the lesser of evils to accept what the United States had basically thrust upon us,” MacKay said. “I don’t think the gun was necessarily to our head -- it was in our mouth, with the trigger cocked and a full chamber.”

Article 32.10 is already a source of debate domestically. The government of Ontario wrote to Freeland this week asking how the clause will “affect future trade deals between Canada and other nations.” Trudeau’s foreign minister defended the deal in her response. “Nothing in this agreement infringes on Canada’s sovereign right to develop commercial relations with any country of its choosing,” she wrote.