Nov 14, 2022

Natural Gas Flaring Is Set to Rebound in Permian Basin

, Bloomberg News

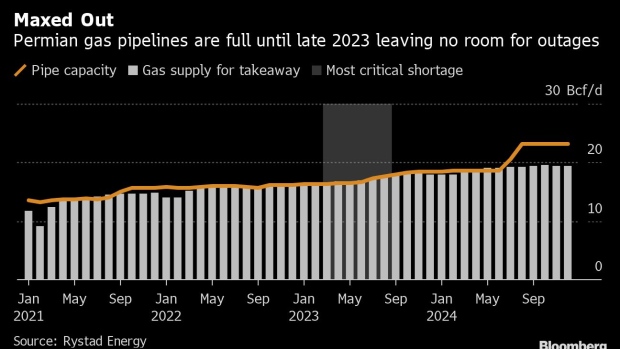

(Bloomberg) -- Operators in America’s biggest shale oil basin are set to significantly increase the amount of natural gas they burn into the atmosphere because of a lack of pipeline capacity to ship it elsewhere, according to Rystad Energy.

Permian Basin gas production has rebounded more quickly than oil since the pandemic, leaving pipelines effectively maxed out. It will be the latter half of next year before several major pipeline expansions come online to ease the shortage.

Producers that haven’t yet secured space on existing pipes face a stark choice: throttle back gas and halt more valuable oil production, or continue to pump crude and burn off the excess gas. Going for the latter would threaten to undo much of the progress achieved in the last few years to address the industry’s flaring problem, which hasn’t just attracted the ire of climate-change activists but also that of ESG-minded investors.

“It’s inevitable that some produced gas will just be flared,” said Alexandre Ramos-Peon, head of shale research at Rystad. Flared volumes could triple to 3% of total production, driven by private operators with less stringent emissions targets, he said.

Burning off gas when many countries are struggling to contain crippling energy costs due to Russia cutting off supplies may seem like a puzzling choice. However, the fuel is mostly a byproduct of more valuable oil in the Permian. Choking back gas production would mean losing out on oil prices of around $90 a barrel, double most operators’ breakeven costs.

As a result, for many companies it makes more economic sense to flare off the gas, especially since permits are easy to receive from the Texas Railroad Commission, the state’s oil and gas regulator. While wellhead flaring is less than half the peak of more than 600 million cubic feet per day reached in 2019, scrutiny from civil society groups and the environmental, social and governance investing movement has grown markedly since then.

Pipeline companies like Energy Transfer LP or Kinder Morgan Inc. typically prefer to build or expand pipelines only when they are confident there will be enough oil or gas to fill them. Build a pipeline too early and there’s a risk of not securing enough flows to repay the high upfront cost, but build them too late and transportation shortages can occur resulting in the need to flare.

It appears the latter is happening in the Permian. The basin’s gas production has increased by more than 30% since the pandemic compared to a rise in oil output of just 12%. Meanwhile the price of gas at Waha, a sales hub in the Permian, has plunged relative to the benchmark Henry Hub, even trading negative last month, indicating a bottleneck in the basin.

“We think our gas takeaway is going to be tight really for most of next year and probably well into 2024 until we get some of the major pipes on,” Diamondback Energy Inc. Chief Executive Officer Travis Stice said Nov. 8.

There’s evidence to suggest that operators may already be stepping up flaring. With pipelines effectively full, any unscheduled outages mean gas has nowhere to go.

“Excess effective capacity is so thin that any kind of upset in maintenance, we’re seeing an instant rise in flaring in the Permian,” said Dzenana Tiganj, a senior analyst at Rystad.

The impact of localized outages can be severe.

In May, problems with a gas-gathering system in Howard County, Texas, meant that private operators connected to it flared 40% of the gas they produced, more than ten times higher than usual levels, Tiganj said.

Flaring levels reduced over the subsequent months as the problem was fixed, Tiganj said, but in October there were signs of more problems in Howard County, with operators’ asking the Texas Railroad Commission for permission to flare even higher volumes than in May.

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.