Dec 1, 2022

Net-Zero Goals Face a New Threat: Government Spending Cuts

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- With US and European governments under pressure to cut spending and narrow deficits, clean energy investments -- and countries’ green goals -- are in new jeopardy, strategists and economists say.

Political pressure to cut spending is rising. The UK is planning tax hikes and budget cuts to stabilize its public finances. In the US, a narrow Republican majority in the House of Representatives portends a showdown over spending. Even Brazil, which just elected the relatively climate-friendly Lula, is keen to signal fiscal rectitude.

Renewable energy can look like an easy place to trim. Solar, wind and hydropower projects, though they lower the cost of energy in the long run, require big upfront costs. Even privately funded developments often rely on public commitments. And wealthy countries’ financial pledges to support clean energy in the developing world becomes a harder political sell when voters are dealing with inflation at home.

“When you are constrained for investment resources, renewables are at a disadvantage,” said Erik Berglöf, chief economist at the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank. “There will be a struggle.”

In recent weeks, financing for the world’s energy transition seemed to gather momentum, with new agreements reached at COP27 in Egypt and at the G20 summit in Bali. Whether others will follow may hinge on how much rich countries are willing to look past near-term inflation, tighter monetary policy and currency turmoils.

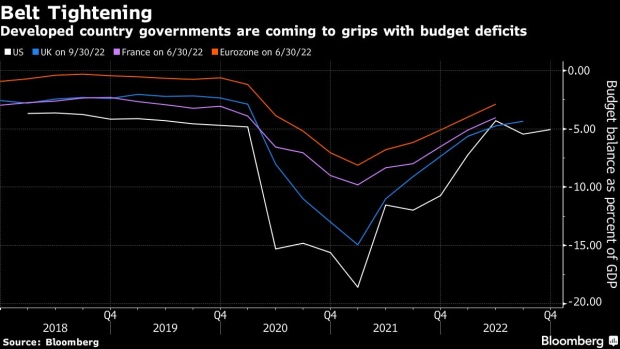

“With some developed markets struggling to balance their government budgets, fiscal woes could add to tighter monetary policy as funding costs rise, slowing down much required green investments,” strategists at Bank of America Securities led by Francisco Blanch wrote in a note.

Sustainable debt issuance has fallen more than 30% this year compared with 2021, according to Bloomberg NEF data. A more unforgiving financial and economic climate won’t make it better: The world economy is forecast to grow just 1.2% next year, a weakness roughly on par with 2009, when the world was still digging out of the global financial crisis, according to the Institute of International Finance.

At the same time, surging energy bills this year may actually spur greater commitment to the energy transition in the long-term, said Grant Mitchell, partner for strategy and transactions at EY.

“CEOs experiencing energy inflation can do a lot of reflection on what energy systems and markets they want to be exposed to in 10 years time,” he said. “Focus on the energy transition could actually increase in this period.”

Moving away from climate-warming fossil fuels and building resilience to the effects of climate change will take more money, not less. The United Nations has said it will take $125 trillion to meet the 2050 targets set by the Paris Agreement. Swiss Re estimates it’s more like $270 trillion.

In a November report, Citi pointed out how important public support is to attract private capital, arguing for guarantees, low-rate loans and other kinds of assurances for outside investors. If the public sector cuts its support for renewable energy projects at home or climate aid abroad, it will discourage private funding as well.

There are some projects which are “very heavily dependent on government policy,” Noel Quinn, HSBC CEO, said at Bloomberg New Economy Forum in Singapore on Nov 16. “Is there an off-take agreement, is it sustainable, will it survive administration change? Those sorts of projects, particularly in the developing markets, need a combination of public sector and private sector finance. They can’t survive alone.”

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.