Dec 8, 2022

Net Zero Will Radically Change How We Use and Generate Electricity

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) --

I have some news that many Bloomberg Green readers will not find surprising: It is exceedingly unlikely that the world will keep global temperatures within 1.5C of pre-industrial levels. But there is still a path to staying under 2C of warming and aligned with the Paris Agreement — a path that requires the global economy to reach net zero emissions by 2050.BloombergNEF, a clean energy research firm, outlines this scenario in its latest New Energy Outlook report.

If we want to get to net zero by 2050, we’ll need much more of every clean technology. That means billions of electric vehicles, trillions of solar panels and a complete transformation of emissions-intensive industrial processes which, to date, have not been meaningfully addressed.

Here I’ll focus on one sector in particular: electricity. Reaching net zero emissions by mid-century will require step-change growth in power generation, a massive rotation in the global stock of existing power plants and, finally, a major change in how that electricity is used.

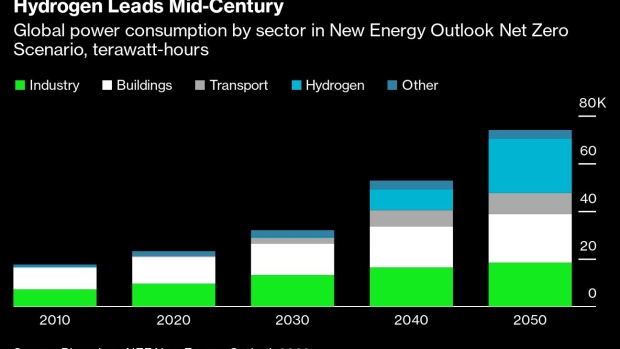

In BloombergNEF’s baseline scenario, the Economic Transition Scenario, power consumption grows by about two-thirds between 2020 and 2050. The Net Zero Scenario, however, has consumption increasing more than threefold compared to 2020.

Driving that consumption on the path to net zero is a new industrial priority: the production of hydrogen. Hydrogen is essential for net zero efforts because it substitutes for fuels in otherwise high-emitting industrial processes. In BloombergNEF’s projection, hydrogen-related power demand grows so much, in fact, that it becomes the main source of demand by 2050, topping both the buildings sector and industry.

The amount of electricity used by the transport sector will rise significantly due to the project of electrifying almost all road transportation. That will require new infrastructure worldwide, and even in its early stages is remaking one of the world’s biggest manufacturing industries. But in energy terms, the electrification of transport is not nearly as significant as hydrogen. Hydrogen of the scale needed for net zero will be a prime mover of global infrastructure.

When it comes to power generation, wind and solar power will grow a lot, of course. On a net zero track, wind installations will need to peak at six times today’s annual rate of installations in only a decade. Solar installations will need to reach more than three times today’s annual rate, but will not peak until 2050.

As these variable technologies become highly prevalent in the global power mix, they also create the need for so-called “firm power” — generators that are always available and reliable during periods when wind and solar are less available. Some of that firm power is needed in short intervals; some of it could be needed for months, or even longer. Firm power will not leave the net zero grid. Far from it.

Firm power will, however, change greatly in composition. Today’s three firm capacity technologies are coal-fired, gas-fired and nuclear power. In capacity terms, coal is currently the biggest, though it is just about at its global peak right now. Gas is not far behind and will also peak in installed capacity. Nuclear power, on the other hand, will expand quite a bit, about one and a half times between today and mid-century.

Coal without any technological fixes to capture emissions effectively vanishes from the global grid by 2050. Gas without carbon capture diminishes somewhat, but not nearly to the same degree as coal.

However, both fuels, with carbon capture and storage, will be key components of global power generation starting in the 2030s. Fitted with CCS, coal and gas will still be able to operate in a net zero emissions world. So, too, will hydrogen, serving much the same purpose on the grid as natural gas.

There is a wrinkle, though, for any company or government planning its fossil fuel power fleet in a net zero world. Given the prevalence of wind and solar generation, and their lowest-cost price position in nearly every power market, fossil fuel generators will no longer play a volume game in the grid of the future. Coal power plant load factors will drop to barely 10% in the 2040s, meaning they will only run one hour out of every 10 in order to support the grid. Gas load factors will drop close to zero. Fossil fuel plants with CCS will fare slightly better, but in a net zero 2050, no fossil fuel-fired power will run anywhere close to all the time.

Nuclear power, on the other hand, will not only expand in installed capacity but operate more often. Nuclear load factors are expected to increase from today’s 80% to almost 90% by 2030, and remain there through mid-century.

A radically different electricity sector is only part of the planet-scale transformation needed for net zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050. But it is the key to new ways of producing essential materials, and for green hydrogen, the input for an entirely new global industry.

Nat Bullard is a senior contributor to BloombergNEF and Bloomberg Green. He is a venture partner at Voyager, an early-stage climate technology investor.

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.