May 19, 2022

New Mix of ECB Hikes Supported by Fiscal Aid Augurs Bumpy Era

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- Sign up for the New Economy Daily newsletter, follow us @economics and subscribe to our podcast.

Europe’s governments and central bankers are moving toward a mix of economic policies that hasn’t been seen since before the global financial crisis, potentially opening up a new era of fretting about markets.

As the European Central Bank considers raising interest rates as soon as July to quell inflation, capitals are acting to support demand via expansionary budgets.

But while the central bank can rein in stimulus now as governments step in with more support, higher borrowing costs will ultimately strain public finances in countries such as Italy.

How long that mix can be sustained will depend on investor appetite to keep bankrolling debt-burdened governments, the ECB’s resolve to fight inflation, and its ability to keep markets under control.

Economists such as Gilles Moec, chief economist at AXA Investment Managers in London, doubt that the euro zone’s new fiscal and monetary combination can be pushed too far.

“In principle, this frees up space for faster normalization by the ECB, but there are limits,” he said. “The test is what the market is going to accept in terms of fiscal stimulus that’s no longer going to be backed by extraordinary monetary policy.”

Assessing the right monetary and fiscal balance will be a talking point for euro-area finance ministers and central bankers as they meet this week with Group of Seven counterparts in Bonn.

Though the ECB has yet to join in the global tightening already being enacted by peers from the US Federal Reserve to the Bank of England, the stars are aligning in Frankfurt for a rate-hiking cycle to begin in July to fight inflation running at a record for the euro area.

That’s the month increasingly cited by policy makers for their first move, with a signal even coming last week from ECB President Christine Lagarde herself.

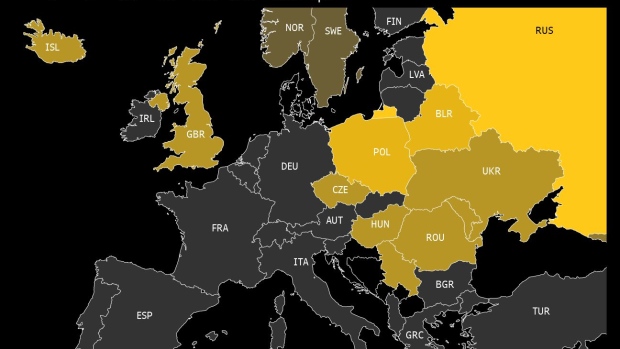

Meanwhile, governments remain firmly in the stimulus mode they first instituted during the pandemic. The euro area posted combined budget deficits of around 7% and 5% in 2020 and 2021 respectively, and while the region had originally planned to conform to lower European Union debt limits as of next year, that’s now unlikely after the outbreak of war in Ukraine.

Apart from alleviating the inflation burden for households and businesses, governments also face greater investment needs to wean themselves off Russian energy and enhance defense capabilities. The costs will total 2% of economic output by the end of next year, with the bulk due in 2022, according to analysis by UBS economists.

Until now, loose monetary policy has supported such largess, keeping government borrowing costs in check both by maintaining ultra-low rates and by buying bonds. That’s now changing, with emergency debt purchases already halted and overall quantitative easing about to cease altogether.

“Up until last year, the ECB was basically buying with the QE program all the net new issuance, and now countries have to place these on financial markets,” said Silvia Ardagna, economist at Barclays in London. “The appetite for investors to absorb larger issuance levels is certainly more price sensitive.”

The market reaction has been a selloff in euro-area bonds, with Germany’s 10-year yield reaching 1% this month for the first time since 2015. The premium over that level that investors demand for holding Italian debt has risen to the highest level since the early months of the pandemic at around 200 basis points.

In case of a blowout in bond yields of weaker euro-zone economies, ECB staff have been working on a crisis tool to deploy that Bloomberg Economics reckons may well be needed in due course.

In any case, emulating a pandemic-era plan to support public finances by pooling borrowing at the EU level might also need to be considered, according to Ardagna at Barclays.

Economists at Morgan Stanley caution that pressure on governments might take time to materialize because the long-term nature of sovereign debt provides some insulation. In a report last week, they stressed that a halt in ECB bond purchases and imminent rate hikes would only impact “over an extended period.”

Moody’s Investors Service said in November that interest payments as a ratio to gross domestic product would average 1.3% in western Europe this year and next, significantly lower than the average in the decade before the pandemic.

Even so, the prospect that higher rates will ultimately put pressure on governments in due course to shore up public finances was raised last week by Bank of France Governor Francois Villeroy de Galhau.

“Our Governing Council will act as much as necessary,” he said. “It’s therefore all the more important that fiscal authorities ensure debt sustainability in a context of rising rates, which has begun and will dominate the coming years.”

The Bank of France estimates that after 10 years, a 1% increase in rates would represent an additional cost of close to 40 billion euros ($42 billion) -- almost the equivalent of the country’s defense budget.

Given the market risks lurking within the euro region, whether the ECB will find itself with much freedom of maneuver to tackle inflation is itself an open question.

“Fiscal is maybe doing a bit more right now and central banks a bit less but we know that the current conditions could turn sour very quickly,” said Ludovic Subran, chief economist at Allianz SE. “It’s hard to imagine a scenario where central banks can really hike how they want.”

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.