Mar 14, 2020

Nightmare on Wall Street Was All About Liquidity

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- Ian Burdette stared at his computer screens on Thursday afternoon in New York and could hardly believe his eyes. Everywhere that the head of term-rates trading at Academy Securities Inc. looked, there were massive anomalies and signs of unprecedented stresses in markets.

Ultra Long Term U.S. Treasury Bond Futures, which moved about 1.3 points per day on average in January, were down more than seven points on the day and off 36 points from Monday’s high. Italian sovereign debt had simply imploded. An index of costs to insure corporate debt with credit-default swaps surged the most since Lehman Brothers collapsed, and the CBOE Volatility Index measuring costs to hedge against losses in U.S. stocks was the highest since November 2008.

In almost every single market, the difference between bid prices from buyers and ask prices from sellers was soaring. The spreads had become, Burdette said, “astonishingly wide.”

“There are so many flashing sirens on my monitors, I don’t know which is the worst,” said Burdette.

As the novel coronavirus continued to spread this week to become a pandemic, financial markets went into a tailspin and rekindled concerns about their ability to function in times of crisis. This is the first major test for the markets since reforms that were introduced after the financial crisis curtailed banks and brokerages from being able to provide liquidity during a turmoil –- in other words, to be a buyer and seller to clients when they need it most.

The market upheaval is exacerbating volatility across assets as investors struggle to determine what they’re actually worth, while the economic outlook grows more dire by the day and uncertainty still surrounds the real impact of the virus.

The evaporation of liquidity was evident across virtually all asset classes, but its absence was most stark in securities which normally serve as havens and see their prices increase during a turmoil. That caused strange, unsettling moves as traders watched long-established cross-market relationships disintegrate.

Treasury 39-year yields unexpectedly rose after their swiftest declines on record, while gold tumbled, even as stocks suffered their sharpest one-day plunge since 1987. The cost to trade Treasuries spiked and order books thinned out to a degree last seen during the 2008 financial crisis.“We were just trying on Monday to trim a long position in the 30-year Treasury because it had moved so far in our favor and we were unable to get bids from several major dealers,” said Mark Holman, chief executive officer at TwentyFourAsset Management in London, who has been working in the business since 1989. “Dealers don’t have the risk appetite and budget they normally have. But I’ve never see that before, the inability to trade a U.S. Treasury. And I’m pretty sure I’m not the only one who experienced this.”

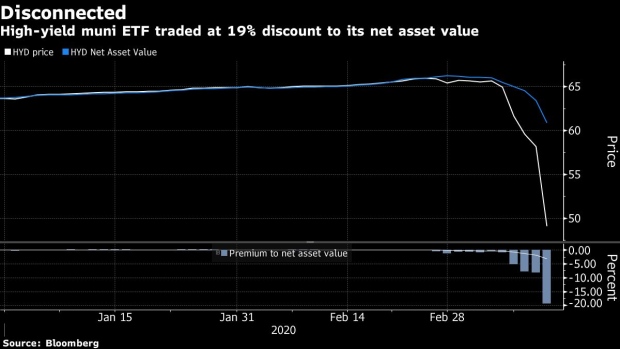

Fixed-income exchange-traded funds became unhinged from the value of the assets they invest in, often at unprecedented rates. The top five largest bond ETFs traded with discounts to their net asset values that were either records or the biggest since 2008. The $23 billion iShares 20+ Year Treasury Bond fund’s price ended Wednesday 5% below the value of its assets. In the almost 18-year history of the product, the average difference between its price and the value of its assets has been 0.03%.

Even the usually quiet world of municipal bonds saw eye-popping volatility. Vanguard mutual funds that invest in municipal bonds from New Jersey and California suffered their worst one-day declines on record, while a New York state muni fund had its worst decline since 1987. The VanEck Vectors High Yield Municipal Index ETF, which holds the debt of hospitals, nursing homes, airports and other borrowers, closed Thursday at a price that was 19% below the value of its assets.

Untangling all of the causes of the various stresses in markets may prove to be difficult, if not impossible. Still, an overwhelming demand for U.S. dollars from corporations and investors is blamed for drying up liquidity. Many companies are being forced to tap emergency credit lines from banks to ensure they have enough cash on hand to continue operating as their revenue streams threaten to dry up.

That is being exacerbated as investor demand for new corporate debt offerings disappears. Funds that invest in U.S. investment-grade corporate bonds suffered their worst outflow on record while investors also retreated from U.S. high-yield and leveraged-loan funds, according to Refinitiv Lipper data. The combined cash withdrawal reached $14.3 billion, exceeding last week’s $12.2 billion record.

“Thursday was a perfect paradigm of the situation we are in,” said Tad Rivelle, chief investment officer for fixed income at asset manager TCW Group Inc. “Basically everything was sold: stocks, all forms of debt, Bitcoin, gold. It looked like a big margin call. You are seeing a large shift in investor preference away from anything besides cash.”

The mad dash for U.S. dollars introduced rarely seen levels of stress into foreign exchange and funding markets. Currency volatility nearly touched levels last seen in 2008 and demand to bet on a rally in the yen over the coming week in the options market hit a record. Rates in cross-currency basis swaps, in which one party borrows in one currency while simultaneously lending the same amount in another currency to a counterparty, are signaling overwhelming demand for dollars. Similar stresses are being seen in swap spreads that exchange fixed rates for floating rates on bonds.

“This is a liquidity squeeze I haven’t seen since the Lehman crisis, not even during the European debt crisis,” said Shinji Kunibe, general manager of global strategies investment department at Sumitomo Mitsui DS Asset Management Co. in Tokyo. “Strategy is for flight-to-cash, flight-to-liquidity.”

Some of the stresses were alleviated Thursday and Friday after the Federal Reserve said it’s prepared to inject a total of more than $5 trillion in cash into funding markets over the next month to ease the cash crunch. It also started to purchase Treasuries across the yield curve.While the Fed’s moves may not prove to be a panacea that cures all of the various markets’ ills, it should at the very least alleviate the need for banks, corporations and investors to hoard dollars.“We don’t think this can turn around risk sentiment; it can’t prevent the upcoming slowdown in consumption and economic activity,” said Elsa Lignos, global head of FX strategy at RBC in London. “But it does mean that financial markets don’t need to hoard liquidity in the way consumers have been hoarding tissue paper and pasta. It shows the Fed has learned the lesson of 2008: pump in liquidity.”

--With assistance from Alyce Andres, Katherine Greifeld, Vassilis Karamanis and Wes Goodman.

To contact the reporters on this story: Emily Barrett in New York at ebarrett25@bloomberg.net;Liz Capo McCormick in New York at emccormick7@bloomberg.net;Chikako Mogi in Tokyo at cmogi@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Jenny Paris at jparis20@bloomberg.net, Michael P. Regan

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.