Aug 16, 2022

No Negative Rates, Less Need for Cash: Euros Return to the ECB

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- Sign up for the New Economy Daily newsletter, follow us @economics and subscribe to our podcast.

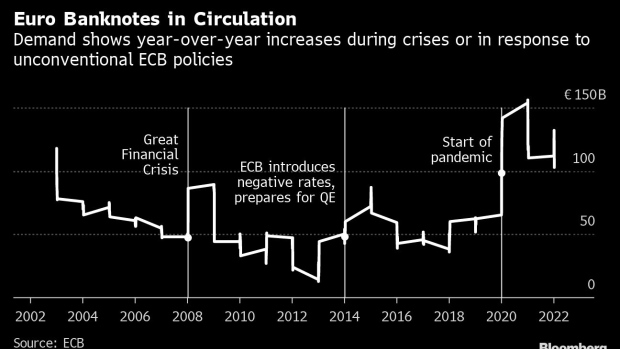

Demand for euro banknotes has dwindled after the European Central Bank concluded an eight-year experiment with negative interest rates, suggesting households, businesses and banks are dissolving cash piles created to circumvent deposit charges.

Banknotes in circulation started falling in the week through July 22, when policy makers raised rates. Since then, notes worth 16.8 billion euros ($17.1 billion) have left the system -- the biggest drop since early 2020.

While the ECB’s weekly financial statements show that declines in January are common after demand surges ahead of the Christmas holidays, they’re rare in the middle of the year. Banking associations in Germany, Europe’s largest economy, say the end of the ECB’s negative-rate policy may be one reason -- though there’s no conclusive explanation for the trend.

“There has been an approximately 1% decline of euro banknotes in circulation (in value) during the past 30 days,” an ECB spokesperson said. “This can be attributed to banks returning higher denomination notes -- mainly euro 500 and 200 -- from the vaults to their central-bank accounts.”

The value of 500-euro notes in circulation fell by the most in three years in July, recording its third-largest drop since the ECB stopped production at the end of 2018 to prevent and rein in its use for criminal activities. The decline in 200-euro notes last month was the biggest on record.

Some 1.6 trillion euros are currently circulating, though only about a fifth is used for transactions within the 19-nation euro zone, according to ECB research last year. As much as 50% is physically stored by households, companies and banks, with the rest held outside the currency bloc.

When the ECB first introduced negative rates in 2014, banks initially absorbed the costs before attempting to circumvent or pass on the charge. More than 580 German lenders collected deposit fees from their customers as of May, according to consumer portal Biallo. That number dropped to 35 as of last week and should reach zero by October at the latest, it said.

That shift in policy may be tempting some consumers and businesses to run down the cash savings they’ve accumulated over the past years. Financial institutions that stocked up on banknotes might be doing the same: German reinsurer Munich Re experimented with storing euros in vaults in 2016, though the trend didn’t quite catch on.

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.