May 23, 2018

No One Said GE's Turnaround Was Going to Be Easy

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- If General Electric Co. makes another cut to its dividend in the middle of a breakup, will it still hurt?

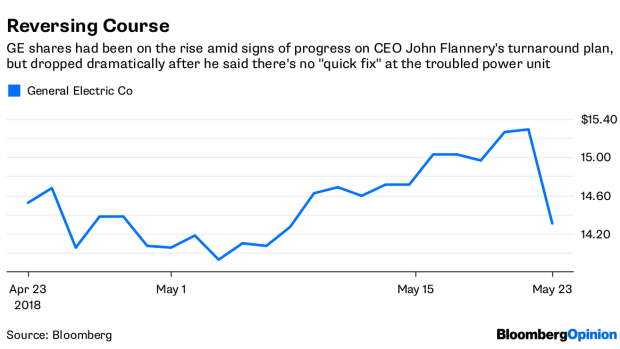

The short-term answer is yes: GE’s stock plunged on Wednesday after CEO John Flannery said the fate of the payout is partly dependent on the steps he takes to unwind the company’s conglomerate structure. Speaking at an annual spring confab for industrial bigwigs, Flannery said he needs to see how the merger of GE's transportation unit with Wabtec Corp. announced this week "plays out". That deal is slated to close in early 2019.

The reaction is logical. It was only six months ago that GE last cut its dividend (for just the second time since the Great Depression, mind you), and that was painful enough. For some, a further reduction would reflect poorly on Flannery's credibility; certainly, it would be proof that the November investor day meant to showcase his turnaround strategy was based on a vision that was far from fully formulated. That said, I think Flannery's approach to the payout and GE's portfolio makes sense. Investors may not have liked it when he said there is no “quick fix”, but they shouldn’t be surprised. I’ve long said the turnaround will be a slow grind.

Flannery’s right to rethink GE's identity and should be contemplating a radical simplification. Inevitably, that's going to mean changes to the dividend. A strategy of making the company smaller but continuing to funnel buckets of cash to investors via buybacks and a plump dividend is a big reason why GE is in this predicament in the first place. Flannery has targeted $20 billion in asset sales, and is about two-thirds of the way there after the Wabtec deal; the $2.6 billion sale of GE's industrial-solutions unit to ABB Ltd.; and a $1 billion deal for a bundle of health-care IT businesses.

The valuation ascribed to the transportation business – a little over $11 billion – is encouraging, and it exceeds what many analysts had been estimating for the unit in their sum-of-the-parts breakdown. This bolsters the idea that breakup math is more of an art than a science, with Excel spreadsheets often underestimating the benefits of a more focused business. In GE's case, there's a clear advantage in freeing businesses from the need to compete with four or five other units for capital, especially in the company's current over-leveraged state.

The problem is that as these GE units go their separate ways, so, too, does their cash flow. Moody's Investors Service pegs the annual cash flow contribution from the transportation unit at $450 million. On the whole, GE has said assets targeted for divestiture excluding industrial solutions represent $1.2 billion of free cash flow. That's a meaningful bite out of the $6 billion to $7 billion GE's targeting for 2018. The dividend costs about $4 billion based on current share count, leaving very little cushion. This unhealthy dynamic is exacerbated by GE's apparent retention of most of the pension liabilities tied to the businesses it divests.

Moody's, which changed its outlook on GE's credit rating to negative last month, took a dim view of the Wabtec merger for these reasons. The firm labeled the deal a credit negative because the complex structure hands most of the value to investors and won’t generate as much cash for debt repayment and pension funding as a straight sale would have. Flannery addressed this on Wednesday, saying he could have sold the transportation unit for cash six months ago if he had wanted to, but would have gotten a lower price and didn't think it was the best outcome.

For the CEO, divestitures are about providing cash for deleveraging and creating value for investors. I get that, but creditors wield power here, given GE's still-heavy reliance on commercial paper. Of concern from Flannery's presentation was a new 10 percent-plus margin target for GE's troubled power unit, compared with an earlier goal in the low-to-mid teens. Flannery says it's a "timing" issue, but Moody's had previously said a perceived inability to get margins in that range could be cause for a downgrade. Absent a material improvement in that business, Flannery will likely have to give something back on the dividend if he wants to do more shareholder-friendly divestitures along the lines of Wabtec. If he can actually pull off a value-creating breakup, maybe that's OK.

To contact the author of this story: Brooke Sutherland at bsutherland7@bloomberg.net

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Beth Williams at bewilliams@bloomberg.net

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.