Oct 6, 2022

Nomura Is Teaching Japan High School Kids How to Invest

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- In the world’s third biggest economy, public skepticism toward financial investing has become so entrenched that investment bank Nomura Holdings Inc. is teaching economic basics in high schools to win over the next generation.

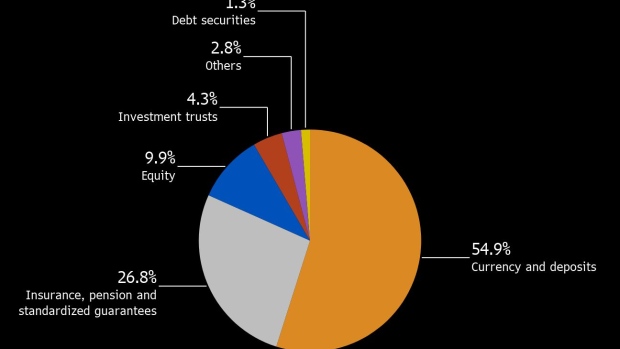

About eight in 10 Japanese have never invested in securities, according to a lobby group for the nation’s brokers. Securities and investments account for only 16% of 2 quadrillion yen in household financial assets, compared with 56% in the US.

An asset-price bubble erased trillions of dollars in wealth in Japan when it burst in the early 1990s, creating a generation of people who believe stocks will only go down. Instead, for decades, most have held the majority of their wealth in cash. That’s left many missing out on a boom in global stocks in the years following the 2008 financial crisis.

Now a goal announced by Prime Minister Fumio Kishida to double Japanese nationals’ income from their assets is set to encourage people to shift more of their savings into investments. Financial education could become a core part of the government’s plan since there is a view that having the right knowledge is necessary for managing assets well.

In April this year, Japan made it mandatory for high schools to teach financial topics - including investments in stocks and bonds - as part of a home economics course.

The financial industry has floated various ideas, with Daiwa Securities Group Inc. Chief Executive Officer Seiji Nakata proposing to make finance part of an entrance exam.

The focus on financial education is set to benefit brokers too. The younger generations including their offspring are increasingly turning to online apps that charge less for trading stocks.

High School

In a class held earlier this summer and taught by Yuki Sato, a Nomura employee, first-grade high school students in the city of Sakai, near Osaka in Southern Japan, filled out a work sheet to calculate how much money is needed to plan their future.

Sato explained the importance of managing income and spending to the 16-year olds. Financially preparing for marriage, child birth, education and other potentially costly events in the future were also covered in the session by the representative from the nation’s biggest brokerage.

There are signs that the younger generation in Japan is more enthusiastic toward investing than their dads and moms. At SBI Securities Inc.’s brokerage unit, the number of accounts opened by 18-year-olds increased by 1,600 in April this year, a sharp rise from the average 130 or so in preceding months. The pace of growth has remained around 1,000 accounts a month since then.

Still, there’s no close collaboration among key players for financial education. Nomura and other private sector companies are individually making efforts, such as sending lecturers to schools. But the Bank of Japan, the Financial Services Agency, the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry and the government office in charge of consumer protection all work separately.

Each can only do so much, while there are no unified standards to ensure the quality of information, said fund manager Haruhiro Nakano, Chief Executive Officer of Saison Asset Management Co.

About seven in 10 Japanese think investing in securities is unnecessary, according to a survey by the Japan Securities Dealers Association. Most recently, there has been a jump in the number of retail investors complaining to the government that financial firms misled them into buying structured bonds, which offer higher returns than regular debt but at significantly higher risk.

Satsuki Katayama, a lawmaker of the ruling Liberal Democratic Party, says she is considering submitting legislation next year to parliament to promote financial education.

Other countries are already ahead. The US set up a Financial Literacy and Education Commission in 2003, in which around 20 government departments and agencies participate.

Katayama thinks it is desirable for “neutral” organizations to spearhead the push, because many banks and brokerages offer advice with an aim to profit themselves. One option would be to establish a third-party organization under the nation’s financial regulator to oversee financial education, and having relevant ministries and agencies check its work as well as set up rules.

“Students are honest, innocent,” said Reiko Komeda, who teaches home economics at the high school. “I think it is important for us to teach them from an unbiased standpoint.”

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.