Jun 18, 2021

Oh, yeah, taper: Fed's stronger liftoff signal causes confusion

, Bloomberg News

Policy divergence between BoC and Fed could be less than expected: Macquarie's David Doyle

The Federal Reserve made some big headlines this week, but for a lot of observers they buried the news.

Investors have wondered for months when it would begin scaling back its massive asset purchases. When Chair Jerome Powell disclosed Wednesday the taper debate was getting underway, the announcement was overshadowed by the surprise that officials had pulled forward their expected timing and pace of interest-rate increases.

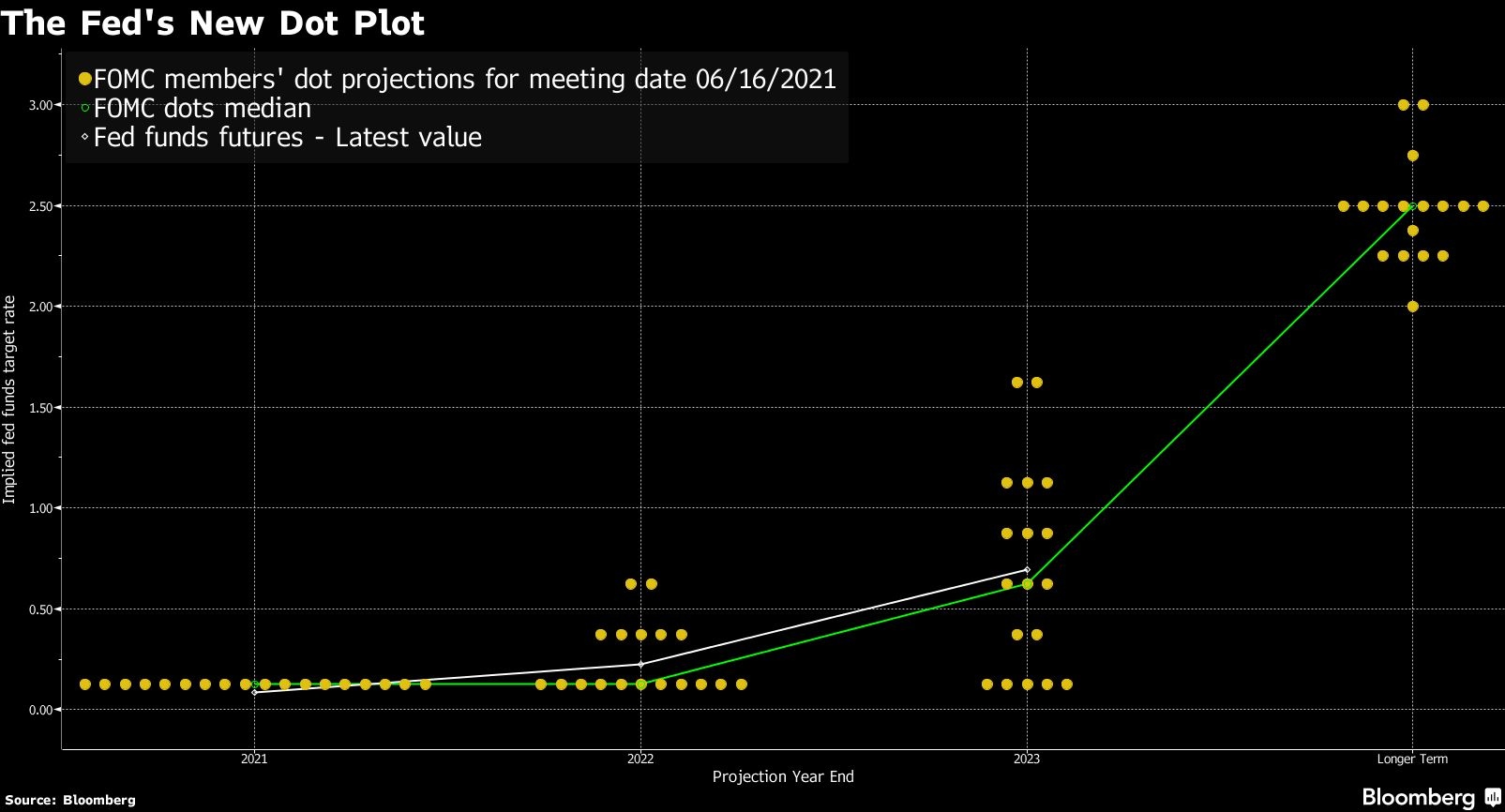

Attention a day later turned back to the timing of tapering, alongside confusion over why the Fed’s dot plot -- a quarterly display of its rate forecasts -- was the tool that signaled it was ready to start ending its emergency pandemic stimulus.

“If you’re worried about inflation, I would have thought that the first thing you do is you pull the tapering lever and not the rate hike lever,” said Roberto Perli, a former Fed economist who is now a partner at Cornerstone Macro LLC in Washington. “The whole thing was a little bit strange.”

Powell, speaking at his post-Fed meeting press conference, went out of his way to avoid saying when the Fed would start the process of scaling back bond buying. Analysts predict a signal in August -- at the Fed’s annual retreat in Jackson Hole, Wyoming -- or September that a move is coming, with the actual announcement later this year. That’s in line with what they expected before this week’s policy meeting.

The Fed chief also played down the signal from the dot plot, urging it be taken with a “big grain of salt” after it delivered a hawkish surprise by showing officials now see two rate hikes in 2023, from none three months ago.

The quarterly projections showed 13 of 18 officials favored at least one rate increase by the end of 2023, versus seven in March. Eleven officials saw at least two hikes by the end of that year. In addition, seven of them saw a move as early as 2022, up from four.

“We did not actually have a discussion of whether lift off is appropriate at any particular year because discussing lift off now would be -- would be highly premature,” Powell told reporters.

There’s no guarantee that he’ll still be in the job when the time comes to hike. His term as chair expires in February and President Joe Biden must decide whether to offer him another four years or pick someone else.

The more hawkish outlook on rates could impact the timing of tapering, as the Fed is expected to follow its playbook from the last time it scaled back bond buying by completing the process before raising rates. But the picture wasn’t clear.

Michael Gapen, chief U.S. economist at Barclays Plc in New York, said it was odd that the committee communicated it had seen enough progress on their goals to forecast a tightening in 2023, “but then say I can’t tell you whether tapering is coming or not or whether we are close to that decision.”

The Fed has been purchasing US$80 billion of Treasuries and US$40 billion of mortgage-backed securities every month to support the economy during the pandemic. On Wednesday, officials repeated they would maintain that pace until “substantial further progress” was made on employment and inflation.

Powell said officials will assess that progress at coming meetings and give financial markets plenty of warning that an announcement to start paring back the buying was coming.

The realization that the Fed has set the stage for taper discussions at future meetings was being digested by investors. Yields on shorter-term Treasuries rose Thursday, while longer-dated bonds rallied as investors decided the Fed was ready to wage war on inflation if necessary.

After the meeting, Goldman Sachs Group Inc. and Deutsche Bank AG both kept their taper timeline forecasts intact, with a signal likely at Jackson Hole or a few weeks later, followed by a formal announcement several months later. Economists at Barclays speed up their taper timeline: they now see a start in November versus January.

Powell has said several times that the central bank will give markets notice of tapering well in advance of the actual start.

Taper, of course, is the precursor to liftoff. Following the 2008 financial crisis, the Fed announced plans to start reducing its purchases in December of 2013 and started doing so the following month. The process ended in October of 2014. Fourteen months later, in December of 2015, liftoff began.

If the Fed were to follow a similar timeline, it could mean liftoff in the first quarter of 2023.

'BIGGER ISSUE'

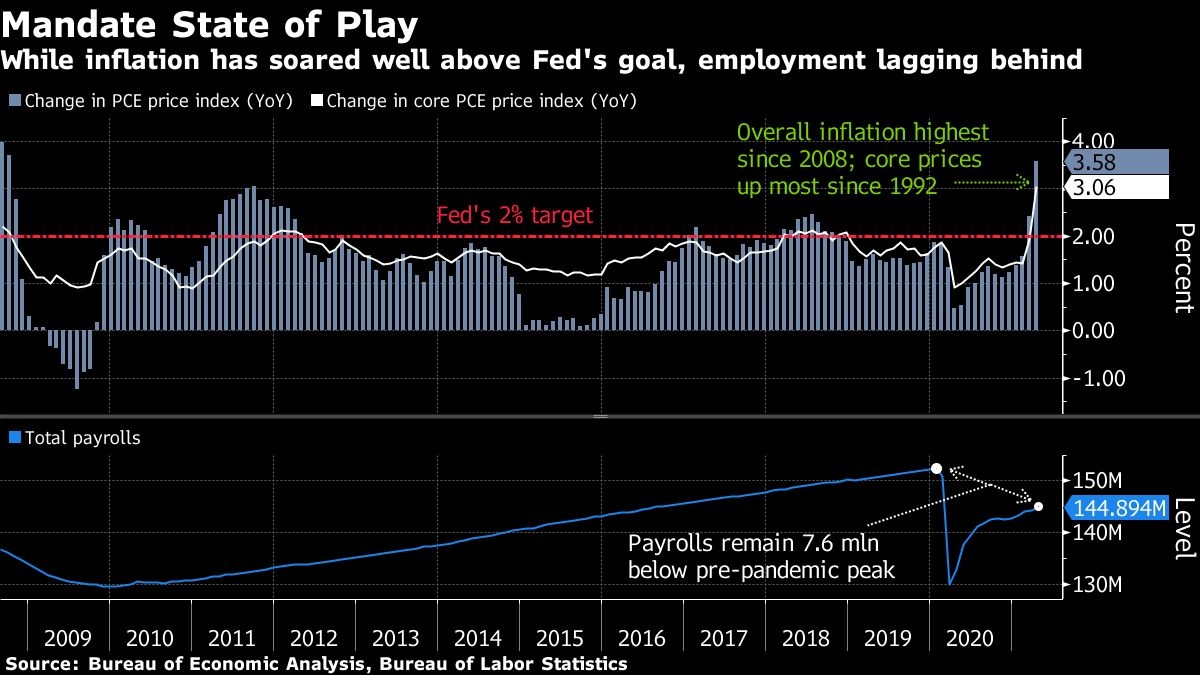

Wednesday’s policy meeting and press conference has also caused some economists to question the Fed’s commitment to its new policy framework, which states that the central bank won’t lift rates until inflation averages 2 per cent over time and it achieves maximum employment, which it’s redefined to be more inclusive.

“The bigger issue is that we were led to believe that the Fed had changed its framework and it was really going to wait a very long time regardless of inflation to see if the labor force healed,” said Erik Weisman, chief economist at MFS Investment Management. “Yesterday, what they did calls that entirely in question. That is a huge policy mistake if they didn’t mean for that to be the takeaway.”

To be sure, there are a lot of unknowns about this recovery, which Powell alluded to when defending the Fed’s commitment to its new strategy.

“All of our discussions and all of our thinking and planning are taking place in the context of our new framework.” he said. “We’re certainly committed to it. We think it’s well suited to our goals, including in this unique time.”