Jul 18, 2019

One of the World’s Most Stubborn Central Banks Gives In

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Asia’s most stubborn central bank just reversed course.

With the Federal Reserve all but certain to renew its easing cycle at the end of the month, the Bank of Korea preemptively cut its benchmark interest rate to 1.5% from 1.75%, in a decision that surprised roughly half of the economists polled by Bloomberg.

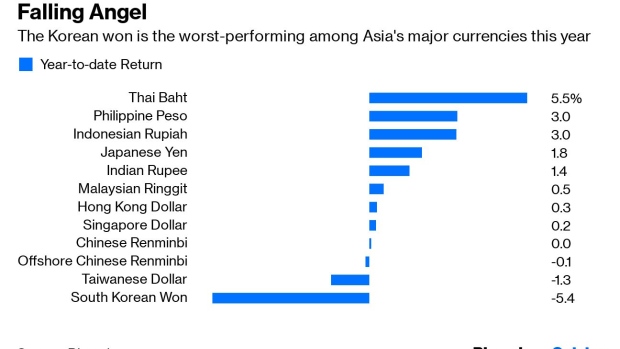

The central bank aimed to calm markets: Once an Asian Tiger, South Korea is now in the doghouse. The Korean won has tumbled 5.4% this year, while its stock market is the region’s second worst-performing after Pakistan, on a dollar basis.

Markets were unimpressed. Bond traders had prepared for this, and the benchmark Kospi Index abruptly declined, falling 0.5% immediately after the rate decision. Kicking off a new easing cycle won’t lift Korea out of its slump.

South Korea is now caught in the crossfire of two trade wars. More than 3% of the nation’s GDP are goods exported to China, which get assembled, repackaged and resold to the U.S. The country’s recent spat with Japan doesn’t help either. In June, semiconductor exports slumped 24.3% from a year earlier.

But the country’s problem runs much deeper than external factors. In the past two years, President Moon Jae-in’s socialist experiments have sapped the animal spirits from this once-vibrant economy. During his rein, consumer confidence fell to a decade low. Some citizens have moved to Vietnam, alongside conglomerates such as Samsung Electronics Co. and Lotte Corp. Even stock investors have preferred to place their bets with the Southeast Asian country.

The most pernicious of President Moon’s policies is a sharp hike in the minimum wage. The government has raised the threshold by 10.9% this year, following a 16.4% boost in 2018. In theory, higher incomes spur consumption, but that hasn’t played out in reality. Last year, job growth tumbled to an eight-year low, as smaller enterprises struggled with expensive staff and conglomerates such as Samsung sped up its relocation to emerging economies. In the fourth quarter, household income in the bottom quintile plunged 17.7%.

Faced with an economic backlash, the Moon administration is now backtracking. The government said this month that it will raise the minimum wage by 2.9% next year, to 8,590 won ($7.29) per hour, well short of the president’s ambitious 10,000-won target for 2020. As a result, labor strikes are picking up, a problem that could have been avoided with more realistic goals.

It may be too late to avoid a capital exodus. Last year, Koreans were the third-biggest buyers of Ho Chi Minh City’s luxury condos, comprising 22% of sales after Vietnamese and Chinese purchasers. President Moon’s property tightening in the capital city of Seoul was seen as heavy-handed.

Meanwhile, the Bank of Korea’s hands are tied. Take a look at how Asian currencies are performing this year. Upending textbook economics, deficit countries such as Indonesia and India are doing just fine, while current-account surplus economies such as China, South Korea and Taiwan are on the back foot.

And just like China, the surplus that Korea has long enjoyed is rapidly disappearing. This gives the Bank of Korea limited room to cut rates further. To avoid a foreign-capital exodus, the central bank has the unenviable task of keeping its rate relatively high.

While rate cuts sound jazzy, they’re no longer an effective tool in South Korea. Rather, a re-thinking of socialist policies is in order.

To contact the author of this story: Shuli Ren at sren38@bloomberg.net

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Rachel Rosenthal at rrosenthal21@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Shuli Ren is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering Asian markets. She previously wrote on markets for Barron's, following a career as an investment banker, and is a CFA charterholder.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.