Dec 6, 2021

One State’s History of Hospital Debt Lawsuits Reveals Racial Gap

, Bloomberg News

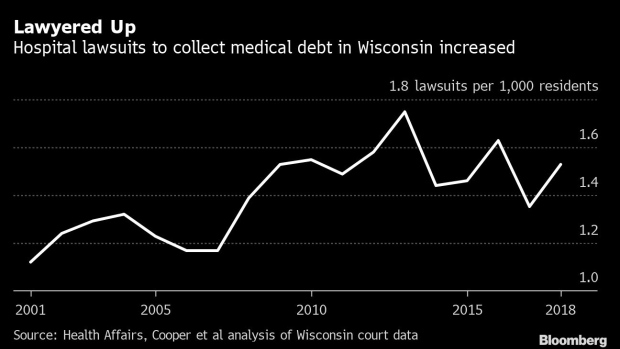

(Bloomberg) -- Hospitals sued patients to collect medical bills at an escalating pace over the past two decades in Wisconsin, according to a new analysis, and the suits disproportionately affected Black people.

The rate of medical debt collection lawsuits in the state increased by more than a third from 2001 to 2018, researchers from Yale University and Stanford University reported in the journal Health Affairs. Lawsuits that led to wage garnishments also rose. The authors called it the first study of long-term trends in such suits by hospitals.

The increase “highlights a fault in our system that we need to think about -- who we want to be bearing these sorts of burdens,” said Zack Cooper, an economist at the Yale School of Public Health who co-authored the paper. “Is that what we signed up for when we started subsidizing these facilities?”

Lawmakers in some states are scrutinizing the methods that health systems use to collect Americans’ estimated $140 billion in past-due medical debt. The analysis found that Wisconsin nonprofit hospitals were more likely to sue than for-profit medical centers.

At the same time, hospital systems often benefit from tax breaks for nonprofit status and additional public funds meant to support treatment for patients who struggle to pay. Under pressure from consumer advocates, several states have passed laws to strengthen protections for patients.

Black Americans are more likely to have medical debt than White, Hispanic, or Asian Americans, Census data show. The Wisconsin analysis found 1.86 lawsuits per 1,000 Black residents in 2018, the highest among demongraphic groups. That compares to a rate of 1.32 per 1,000 White residents, 1.1 for Hispanic residents, and 0.11 for Asian residents.

The analysis wasn’t able to determine whether Black patients are treated differently than others when bills go unpaid, or if the disparity in lawsuits reflects underlying inequities in other factors like wealth or insurance coverage.

Rates of lawsuits directed at poor patients and in rural areas were higher than rates of other groups. Much of the increase in collections lawsuits followed the 2008 financial crisis.

Court Data

The researchers focused on Wisconsin because the data was relatively accessible and the state didn’t expand Medicaid, which could influence results, Cooper said. The team eventually hopes to compile similar data from other states.

Matching cases to hospital names, the researchers culled years of court data from state records. They inferred the race of patients involved through a method that combines geographic data and names, a technique outlined by the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau.

The results aligned with other examinations from advocates in New York and Maryland that show widely varying practices among different hospitals. Not all hospitals sue their patients, and some sue a lot more often than others.

Pursuing collections lawsuits is “clearly a decision that’s being actively made by some institutions,” Cooper said. “This is not something that’s just sort of happening.”

The study was supported with a grant from Arnold Ventures, a philanthropy that often spotlights high health-care costs.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.