Nov 5, 2019

OPEC sees market share shrinking for years as shale triumphs

, Bloomberg News

OPEC Forecasts Demand to Fall 7% by 2023

OPEC slashed estimates for the amount of oil it will need to pump in coming years, projecting that its share of world markets will shrink until the middle of the next decade amid a flood of U.S. shale supplies.

The producer group expects that demand for its oil will slide by about 7 per cent over the next four years, slumping to an average of 32.7 million barrels a day in 2023, according to its annual report.

That could compel the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries and its partners -- who have already curbed output this year to prevent a glut -- to reduce supplies even further, or at least compete more fiercely among themselves for a diminishing portion of global markets.

The organization cut forecasts for demand for its oil each year from 2019 through 2023 by an average of about 5 million barrels a day, or roughly 16 per cent, though the numbers have been affected by membership changes. Qatar left the group at the beginning of this year.

OPEC will remain under pressure from rising U.S. oil output. America has become the world’s top oil producer through developing hydraulic fracturing, commonly known as “fracking,” in states such as Texas and North Dakota.

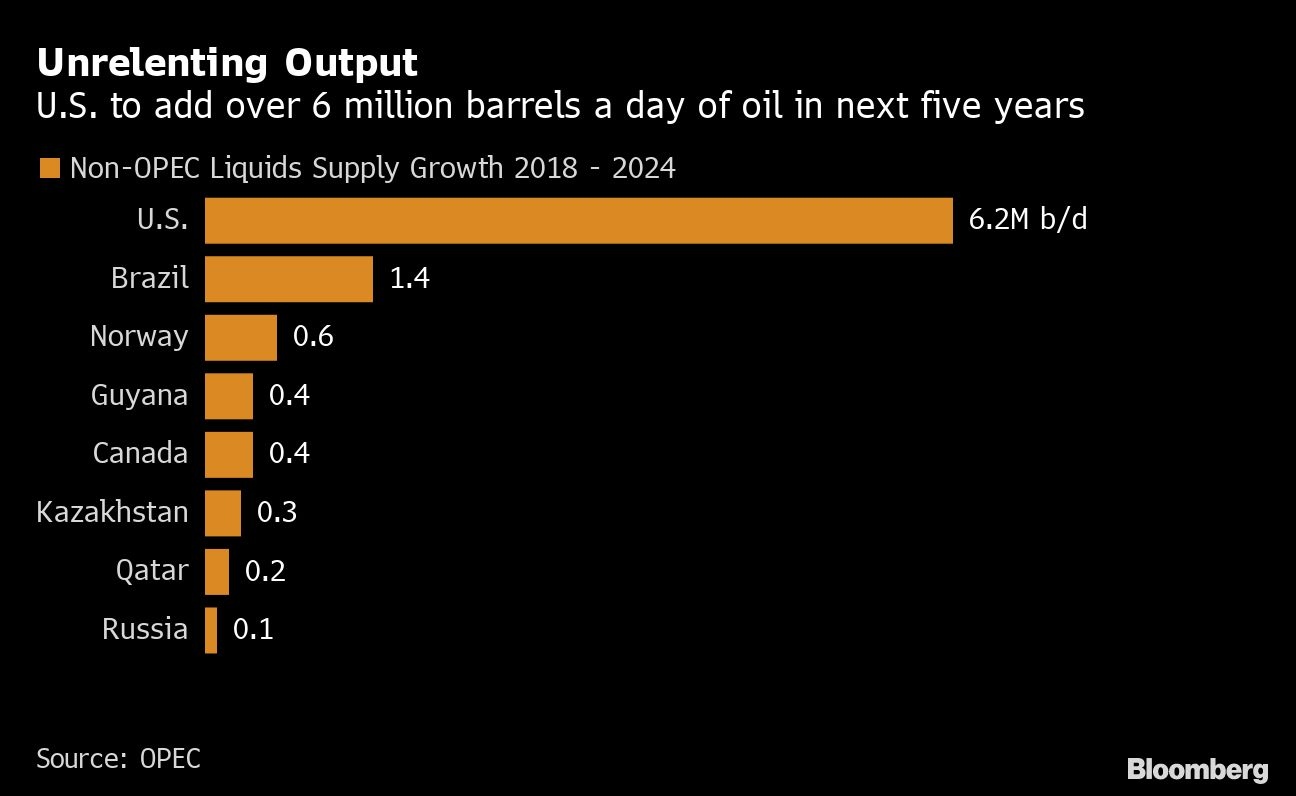

“The main driver of medium-term non-OPEC supply growth remains overwhelmingly U.S. tight oil,” OPEC said in its latest World Oil Outlook, using another term for shale oil.

By 2025, U.S. shale-oil output will climb more than 40% to reach 17 million barrels a day, or 3.1 million a day more than OPEC projected in last year’s report. American oil will account for a fifth of global daily output at that time.

But the U.S. deluge will also be supplemented by supplies from regions which had either seemed in decline or uneconomical in an era of constrained crude prices, such as offshore Norway and Brazil, as well as Canada, Guyana and Kazakhstan.

OPEC and its partners are due to meet next month in Vienna, and will consider whether to deepen their current output cutbacks to avert another glut in 2020, according to the organization’s secretary-general Mohammad Barkindo. Russia, the most important of OPEC’s allies, has been more cautious in signaling what needs to be done.

Some members of OPEC+, including Russia, are still falling short on their pledged cutbacks. But the coalition has considerable incentive to double down on its efforts: oil prices, currently just above $60 a barrel in London, are too low for most OPEC nations to cover government spending, including Saudi Arabia, the group’s biggest member. Riyadh may also need higher prices as it sells part of state-owned oil giant Saudi Aramco, in what may prove to be the world’s biggest-ever initial public offering.

Yet the findings of this latest report could make them consider whether the strategy is backfiring, by propping up investment in U.S. shale drilling and perpetuating an oil oversupply. Many analysts have said the group should have heeded the warning of former Saudi oil minister Ali al-Naimi, who predicted that by making room for shale, OPEC would be trapped in an endless spiral of production cuts.

OPEC’s current share of the global market is about 35 per cent, a level it sees dwindling by 2025 to 32 per cent, according to the report.

At the same time, the report does offer OPEC some solace if it chooses to stay the course. U.S. shale output growth will slow from the middle of the next decade, and then begin to decline from 2029 onward. OPEC’s share of the global market will rebound to 40 per cent by 2040.

Although it sees challenges from rival supplies, OPEC’s outlook shows less concern about demand. The report projects that global crude consumption will continue to grow until at least 2040, rejecting the idea increasingly circulating among investors and oil companies that demand will “peak” as countries move away from fossil fuels to avert catastrophic climate change.

While OPEC did lower demand forecasts, it said the reduction reflects a weaker economic backdrop rather than a shift away from carbon. Global oil demand will increase at a “healthy” rate of 1 million barrels a day until 2024, when it will reach 104.8 million barrels a day, then expand at a slower pace, to hit an average of 110.6 million a day in 2040.