Jun 29, 2018

Ottawa’s tariffs target the U.S., but will Canadians bear the brunt of higher prices?

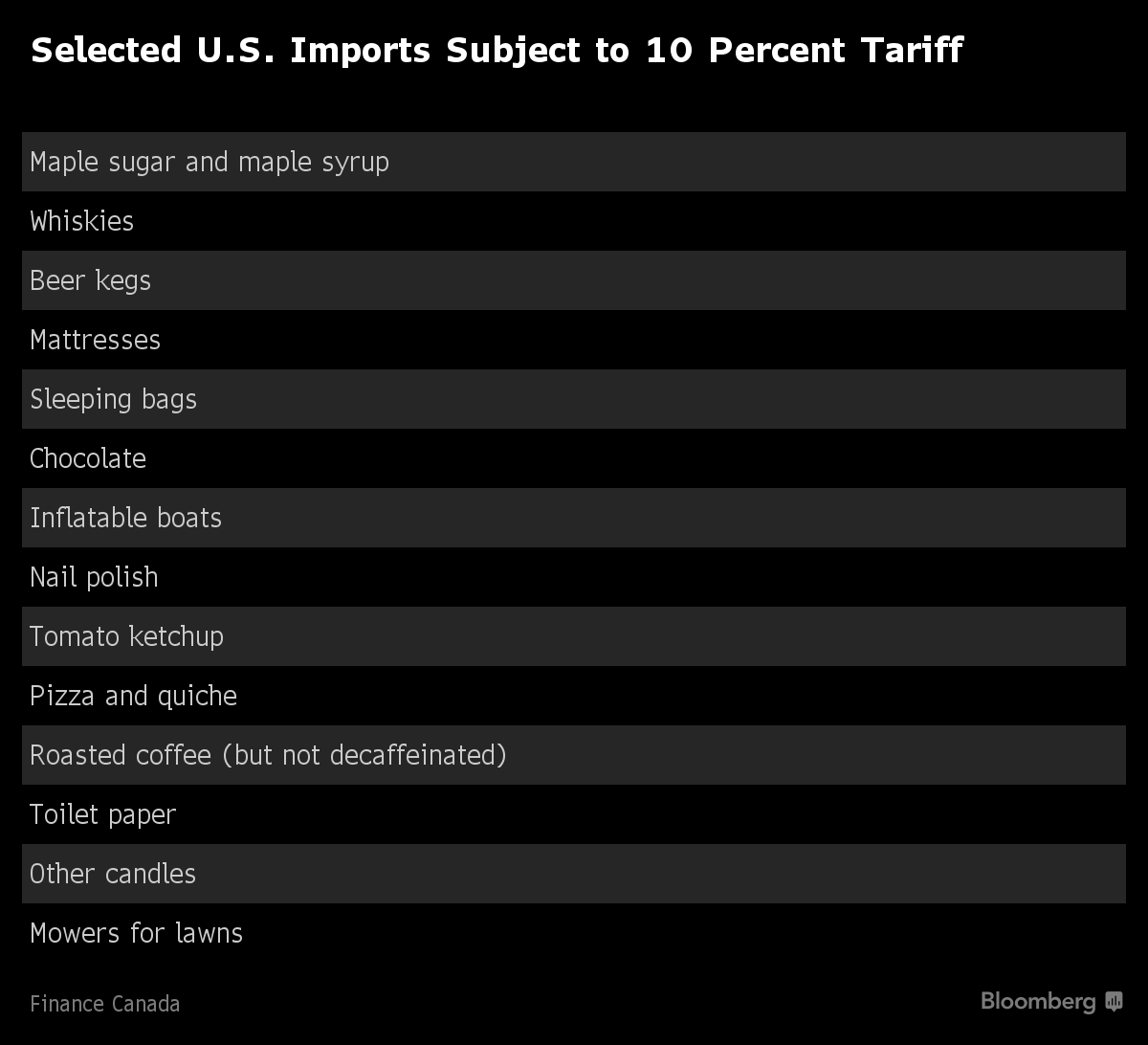

From pickles and plywood to toilet paper, Canada’s retaliatory tariffs on $16.6 billion worth of U.S. goods come into effect July 1.

The federal government’s 25 or 10 per cent surtax on a wide-range of U.S. consumer goods and manufacturing products is meant to hurt businesses and the economy south of the border, but how much will the higher cost of importing such goods drive up prices for Canadians?

Economists tell BNN Bloomberg that Canada’s tariffs will have an immediate impact on consumer prices, although it will be “very small.” But they warn the impact of higher costs on intermediate goods such as steel or aluminum would be more difficult to see.

Douglas Porter, chief economist at BMO Financial Group, said Ottawa’s new measures would add 0.1 to 0.2 percentage points to Canadian inflation.

“Presumably, it would work its way into inflation fairly quickly on some products, but have a bit more of a time delay on others – say where steel and or aluminum are used as an input [in production],” Porter said. “But, we estimate that the full effect would play out within six to nine months for prices.”

The latest data from Statistics Canada showed that the consumer price index (CPI) in May was unchanged from April at 2.2 per cent and fell well below economists’ expectations of a 2.6 per cent rise.

Brian DePratto, senior economist at TD Economics, also estimates a 0.1 percentage point increase to inflation from the tariffs, but was quick to point out that the rise is very small when compared to other drivers such as energy prices or changes in the exchange rate.

“Put simply, the value of the goods affected isn't that large when compared to the overall import pie, or to consumer spending,” DePratto said. “Potential substitution effects (i.e. buying Canadian substitutes) would further mute the impact.”

COSTS ‘EATEN’ BY BUSINESSES

Meanwhile, Royce Mendes, senior economist at CIBC Capital Markets, added the tariffs on consumer goods might not be completely passed on to consumers and could be, at least partially, “eaten by businesses.”

“It’s probably even less than a tick on inflation from the tariffs on consumer goods,” Mendes said.

“Whatever inflation it produces, it isn’t the type that would induce a more aggressive pace to rate hikes from the Bank of Canada,” he added. “Tariff-induced inflation is a one-time change increase in the level of prices.”

But inflation aside, Mendes said that tariffs on intermediate goods could have more adverse effects on economic activity as businesses absorb the higher costs on imported goods.

Companies that eat up the higher costs for products like steel, aluminum, and circuit boards from the U.S. during the production process would make it difficult to assess the impact on inflation, said Mendes.

“It could be difficult to see them, because they would be only one part of a final consumer good,” he said. “They could also go into a capital good (i.e. a piece of machinery), which then wouldn’t show up in CPI unless it raised [the price of] whatever final consumer good it was producing.”

“The tariffs on intermediate goods would be more difficult to see in CPI, but you could see them show up in reduced corporate profits at affected firms,” he added.

Industry associations that use intermediate goods facing tariffs both sides of the border such as auto parts makers have been sounding the alarm about the damage their sectors could face from the higher import costs.

But Mendes also pointed out that some of the products which use these intermediate goods as an input are going to be exported by companies and will not be consumed in Canada.