Apr 20, 2018

'Over my dead body': Meet the man standing in the way of a Trans Mountain alternative

Andrew Weaver wants to know why Canada is so focused on the Trans Mountain expansion while the British Columbia Green Party leader considers another pipeline a much more viable way of moving diluted Alberta bitumen to the coast.

“Why haven’t we talked about the Eagle Spirit project?,” Weaver asked in a BNN interview earlier this week, referring to a $16-billion proposal to build a million-barrel-per-day oil sands pipeline through northern B.C. “The one up in Prince Rupert with 100 per cent support by First Nations, why aren’t we talking about that?”

This is why:

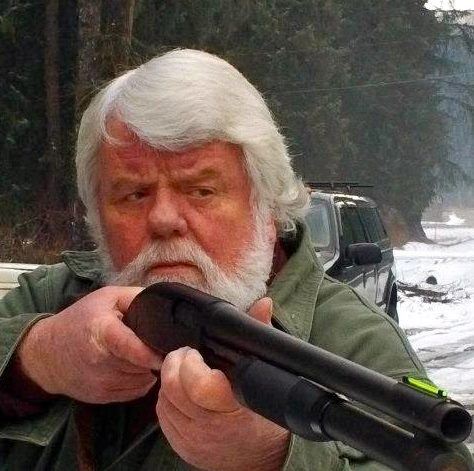

“No, that ain’t happening, it’s just ridiculous,” Wes Loe, mayor of the remote Alaskan border village named Hyder – where Eagle Spirit now plans to end its 1,600-kilometre pipeline – told BNN via telephone from the General Store he runs in the town of about 90 permanent residents.

“That is about as likely as a space ship launch pad being built here.”

When it was first proposed in 2012 as an alternative to Northern Gateway, Eagle Spirit was lauded both for its First Nations credentials – company president Calvin Helin is a member of the Lax Kw’alaams and is guided by a Chief’s Council – and for its more environmentally palatable siting strategy – it would be constructed along a utility corridor that would also house gas pipelines, hydro lines and fiber optic cable.

Then, in 2016, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau announced a moratorium on crude oil tanker traffic in Northern B.C. coastal waters. While Eagle Spirit’s backers have pledged to fight the proposed ban – though a GoFundMe page to cover legal costs has raised less than half of its $100,000 goal over the past four months – the company was forced to develop a backup plan, moving its proposed endpoint 400 kilometres north of Prince Rupert to Hyder, Alaska.

“The reason [Hyder] is viable is because if you just go across the American border, we can legally ship Canadian crude out under the American flag,” Helin told BNN in an interview Friday, adding he will be meeting with British Columbia Premier John Horgan later in the day. “I can tell you without any reservation at all at the highest levels of government in Alaska we have been told we’ll be welcomed with open arms.”

Eagle Spirit might think moving the terminal just slightly outside of Canadian jurisdiction makes sense, but Loe argues otherwise.

“I don’t want oil tankers coming up this canal,” he said, referring to the 210-kilometre fjord known as the Portland Canal that forms a portion of the Canada-U.S. border that runs past Hyder, “I don’t think anyone else who lives out here would.”

“Who the hell would want to come here and ruin all the genuine potpourri of wildlife we have here?” Loe said. “Over my dead body.”

Hyder lies just three kilometres down the road from Stewart, British Columbia – a larger settlement of about 500. The Americans in Hyder rely on their Canadian neighbours for everything from electricity to police services. They are the only Americans with a Canadian area code (250) and their children attend Canadian schools.

- Trans Mountain dispute shows Canada has 'trouble getting our act together': David Dodge

- Ottawa needs to use 'point of leverage' in Trans Mountain dispute: Brad Wall

- From calls to 'stand down' to job losses, B.C. groups debate Trans Mountain

MORE ON PIPELINE POLITICS

Stewart mayor Galina Durant is also skeptical of the Eagle Spirit pipeline plan.

“I don’t see how it would be feasible labour-wise, construction-wise or even space-wise,” Durant told BNN via telephone Thursday evening. “Never mind all the environmental approvals. There really isn’t enough space, Hyder is a small place.”

“A more feasible option would be an LNG [liquefied natural gas] terminal in our area,” Durant said, “but crude oil? I don’t see that in my lifetime.”

Down the road and across the international boundary, in Hyder, Loe is standing firmly against a project he believes could literally destroy his community.

“You’d have to clear out everybody’s home in Hyder in order to fit in all the fuel tanks and storage facilities,” he said. “The state of Alaska would never allow that.”