Nov 9, 2021

Pandemic Blows Up Old Business Habits, Opening Path to a Boom

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- Jon-Michial Carter was the biggest skeptic of remote work when one of his managers suggested they test the idea in 2019.

“We had a 100,000 square-foot facility full of clinicians delivering remote virtual care,” said the founder and chief executive of ChartSpan, a chronic-care provider based in Greenville, South Carolina. “It seemed inconceivable that we could send them home.” When Covid-19 arrived in 2020, that’s what the firm did. As a direct result, it’s making more money. Employees say they’re happier, and the numbers say they’re more productive.

Similar, potentially seismic shifts could be under way across the business world.

The pandemic has killed more than 750,000 Americans and left millions more out of work. But something else has been happening too. The shock forced managers everywhere to try doing things differently, accelerating innovation.

It “opens the door to this radical newness in the way businesses are configured,” said Jason Thomas, head of global research at Carlyle Group.

Like other economic indicators, U.S. productivity -- a measure of output per hour that’s central to long-run prosperity for companies and workers -- has been volatile in the pandemic. Millions of Americans have moved into new jobs that they’ll need time to master.

Productivity sank in the third quarter, as the delta variant of Covid-19 held back growth right after a summer wave of hiring. Earlier in the year it had been growing at a pace well above the past decade’s average. It’s too early to call the long-run trend.

‘The Entire U.S.’

Still, plenty of data and anecdotes point to a deepening use of technology across a range of businesses, allowing them to scale up without much added cost.

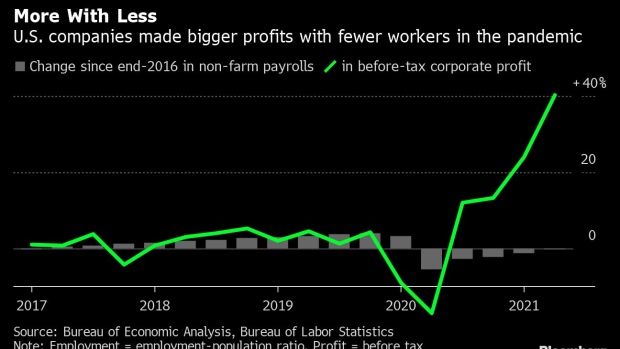

That’s reflected in corporate profits, which rose 10.5% in the second quarter to a record $2.8 trillion. Strikingly, that was achieved with fewer people working: Non-farm payrolls in June were still down by some 6.6 million from pre-pandemic levels.

How productivity happens, and how to measure it, are big questions to which economists don’t have good answers. It’s an elusive gauge of how labor and capital combine to produce more. When they manage that, it means economies can grow at a decent clip even when populations are steady -- and employment and pay can rise without triggering inflation.

New equipment is one route to achieving this goal, enabling workers to lift their output. But new forms of corporate organization can achieve the same effect.

‘Numbers Like That’

That’s what happened at ChartSpan, whose downtown location in Greenville was a landmark of the city’s strong start-up culture. It had an open-floor layout, and when a nurse was needed to get on the phone with a patient, caregivers signaled with a raised hand.

When the pandemic hit, the company had little choice but to work from home, building off a small remote-work pilot program. The early returns astounded managers. Employees were doing more, with greater efficiency and flexibility, while the company’s bottom line was growing. “We had never seen numbers like that in our history,” Carter said. “Our workforce went from Greenville, South Carolina, to the entire U.S.”

There’s more to pandemic productivity gains than just work-from-home. It’s happening as companies find new ways to match their staff, the demand from their customers, and technologies that may have been around a while before businesses settle on the best ways to use them.

Target Corp., for example, has been investing in digital business since 2017, to adapt to stores that would also serve as distribution hubs for pickup or delivery. When the pandemic hit, spiraling demand led to big gains in productivity. Target expects sales to reach $100 billion this year, up 35% from 2016 with a 20% increase in headcount. “The choice doesn’t have to be about people or technology,” Chief Operating Officer John Mulligan said on an earnings call in August. “We can invest in both people and their productivity.”

‘Path Dependency’

Target is passing some of the gains to its labor force, raising its starting wage to $15 an hour last year and offering help with educational expenses. Since worker pay across the U.S. has lagged productivity growth for decades, there are likely battles ahead about how the fruits of productivity are shared out.

That’s if recent increases can be sustained. Michael Feroli, chief U.S. economist at JPMorgan Chase & Co., is skeptical. “The good numbers over the past six quarters are not enough to declare a new paradigm,” he said. Productivity always picks up after slumps, he said, and corporate profits are tied to the economic cycle and are currently getting a boost from strong consumer demand.

Still, company after company is finding ways to innovate. Carlyle’s Thomas calls it breaking “path dependency” -- the tendency to do things a certain way because they’ve always been done that way.

Thomas gets a firsthand look at this by peering into the 267 companies in the private equity firm’s portfolio. Revenue per worker has increased more than 12% and operating margins are up 24% from before the pandemic, he said.

‘Whole New Level’

Along with labor shortages, much of the innovation, especially in service industries, stemmed from the need to meet the demands of customers while protecting them from infection risk. Think of the yoga studio that went mostly virtual. It required investment in technology -- software, cameras, microphones and large screens. Once all of that was in place, the number of people who could drop in for a class was no longer limited by the studio’s size. Or take Kyocera SGS Tech Hub, a maker of sophisticated cutting tools in Danville, Virginia. Workers there have adjusted shifts to reduce contact. But the biggest change, said Jason Wells, its president, is the way the pandemic increased communication -- putting employees in closer contact with each other and with suppliers, which helped them solve problems faster. “This situation added a whole new level of communication, connection, and honestly, efficiency to our organization that did not exist prior to the pandemic,” said Wells. “I am not saying we may not have gotten there eventually. But necessity is the mother of all great invention.”

‘Every Intention’

Technological adaptation is never instant or smooth, which is why the question of whether the pandemic boosted productivity won’t be answered for a long while.

At ChartSpan, the remote-work pilot program failed initially to deliver the expected “major lift” in productivity and client satisfaction, said Meredith Oh, vice president of operations. Some of the problems were unexpected -- the biggest one, early on, was dogs barking during calls with patients -- and there were broader shortfalls in technology and training, which were addressed when ChartSpan staff had to abandon their office cubicles as the pandemic escalated. “We went remote with every intention of coming back,” said Oh. But as costs plunged, employee satisfaction rose, and output increased, they never did. Instead they began to ask themselves why they were all sitting in cubicles in Greenville in the first place. “I’m amused by all the folks who say we are going to return to normal,” Carter said. “This is the new normal. This is how we are going to work.”

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.