Jul 12, 2019

Panic Sales Rekindle Debate Over ETF Liquidity in Next Crisis

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- A couple of prominent investment funds are currently living through a portfolio manager’s worst nightmare: So many customers are demanding their money back that withdrawals need to be frozen.

Amit Deshpande, a former longtime risk manager, sees it as a wake-up call. In particular, he’s watching the growing ranks of asset managers who rely on ETFs to act as cash equivalents. He wonders whether the funds can be sold off to pay fleeing clients in times of stress as seamlessly as the stewards of the $4 trillion market would like.

In other words, are exchange-traded funds the ATMs many managers believe them to be? Or will they fail to sell quickly enough and at sufficient prices during a crunch to fulfill customer demands?

“We’ve taken a bunch of semi-liquid securities, put that into an equity wrapper, said now you’re an equity and now you’re liquid,’’ said Deshpande, currently head of fixed income quantitative investments and research at T. Rowe Price Group Inc. “It doesn’t always work that way.’’

Client Withdrawals

Skeptics have long questioned how easily ETFs can be turned into cash during a sell-off. But most of the focus has been on the funds facing their own client withdrawals, not money managers holding ETFs to pay off investors in other kinds of funds.

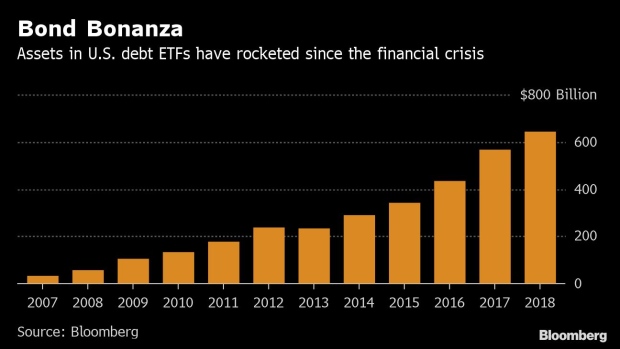

The growing concern comes as active managers such as U.K. stock picker Neil Woodford, Switzerland’s GAM Holding AG and London-based H20 Asset Management grapple with redemptions. Bond ETFs in particular are eliciting alarms. They account for less than 1% of the fixed-income market, but assets have grown quickly to $1 trillion and they’re increasingly popular as cash substitutes.

About half the institutions that own bond ETFs are using them for cash management, according to a survey by Greenwich Associates. Eaton Vance Corp. uses a loan ETF to avoid cash drag in its short-duration strategic income fund, for example.

Fund Liquidity

Much depends on the mismatch between the liquidity of the funds, which trade every second, and that of the securities they own. Proponents argue that this means ETFs better reflect the value of their holdings than slower-to-react mutual funds. But concerns linger that any breakdown in the relationship between the prices of the funds and their securities, particularly in fixed income, could imperil owners.

The European Systemic Risk Board recently warned that price decoupling could raise systemic risk by destabilizing institutions that rely on ETFs for quick cash. The U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission didn’t respond to requests for comment.

Boosters say that ETFs are ideal cash replacements thanks to a unique structure that makes them more liquid than other types of funds. While ETFs expand and contract as money flows in and out, they also trade on exchanges like stocks.

Secondary Trades

Secondary trading means there always should be a market. When an ETF’s price falls below the value of its holdings, sophisticated traders step in to buy the discounted ETF shares and swap them for the underlying securities. The traders can then sell those securities at the higher price, earning an arbitrage and bringing the price of the ETF back in line with its value.

The world’s largest junk-bond ETF, the iShares iBoxx High Yield Corporate Bond ETF, sees about six shares trade in the secondary market for every share that’s created or redeemed on an average day, according to Bloomberg Intelligence. In times of market stress, that ratio can spike as high as 20 to 1.

ETFs “absorb market activity as underlying bond trading recedes,” BlackRock Inc., the world’s largest issuer of ETFs, said in a paper last month.

Flash Crash

Not all U.S. bond ETFs are created equal, however. Though three of them trade more than $1 billion shares a day, half see turnover of less than $1 million. While ETFs are designed to meet redemptions with securities, funds that own leveraged loans or overseas debt usually hand out cash, tempering the arbitrage opportunities that keep fund values in line with their holdings.

“When someone wants to look at an ETF very specifically for liquidity-management purposes, of course they should look at how actively traded that particular ETF is within that sector,” said Stephen Laipply, head of fixed-income strategy for BlackRock’s U.S. ETF business.

Even the structure itself isn’t bulletproof. During the flash crash of Aug. 24, 2015, market makers on the exchanges found themselves unable to price ETFs as futures contracts went dark, and hundreds of ETFs temporarily stopped trading after the resulting volatility triggered exchange limits. In June 2013, Citigroup Inc. stopped redeeming ETF shares for clients after hitting its internal risk limits. Last year, two banks stepped away from a cannabis ETF after it changed custodians.

Tighter balance sheets in the wake of the financial crisis have also encouraged some banks to scale back ETF trading. Electronic brokers have stepped in, but fears remain that they could back away in a volatile market, leaving funds to trade at a discount. Investors would still be able to sell, just not at the price they might like.

“To say this is a foolproof mechanism,” Deshpande said, “let me just say, it needs to be tested.”

To contact the reporters on this story: Rachel Evans in New York at revans43@bloomberg.net;Emily Barrett in New York at ebarrett25@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Jeremy Herron at jherron8@bloomberg.net, Bob Ivry, Larry Reibstein

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.