Oct 11, 2019

Poland Backing Wind in Heart of Coal Country Shows Power Dilemma

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- As he stood outside a coal mine during a campaign stop last month, Poland’s Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki surprisingly touted the project’s green credentials.

“Without investments like this one, we wouldn’t have renewable energy and other industries that we are betting on,” Morawiecki told a crowd of miners in Silesia, the country’s coal heartland.

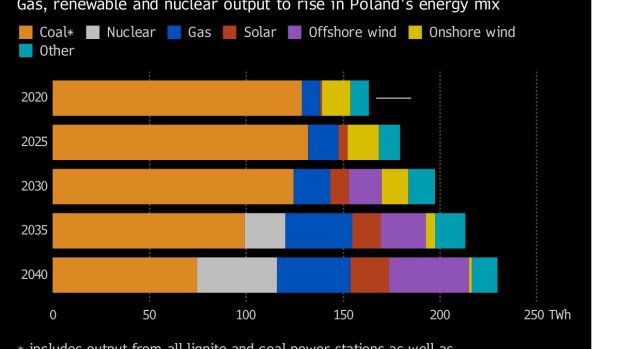

The mention of renewable energy at all, in the weeks leading up to an election on Sunday, marks a change of tone in the country, which gets most of its power from coal and has previously stifled renewable investments. With wind and solar costs plummeting and an increasing public backlash against some of the dirtiest air in the region, the government is changing its rhetoric on energy and looking to the European Union to help finance the transition.

In fact, the new mine that Morawiecki praised won’t even supply any power plants. Instead JSW SA’s Bzie Debina project, which the EU’s largest metallurgical coal producer plans to complete in 2022, would feed steel production that could be used for windmill parts at a time when Poland wants to build most of the supply chain for offshore farms, the prime minister said.

Morawiecki’s Law & Justice party came to power in 2015 thanks in part to support from miners. In its first year, the government nearly halted the fast-developing onshore wind industry with restrictive laws. At the same time, it revived a 1 gigawatt coal-fired power plant project in Ostroleka -- whose backers now struggle to find financing.

A tripling in the price of emission permits last year also hit Polish coal hard, with wholesale power prices currently about 25% above levels in neighboring Germany. The government stymied the impact to consumers by freezing household electricity rates and limiting the increase for businesses.

Then last year, the government held an auction for new onshore wind projects. Developers, including state-owned utility PGE SA and international players EDP Renovaveis SA and Innogy SE bid to sell power at prices that were far below what the market had expected.

“That was a big turning point,” said Bart Dujczynski, founder of Proventus Renewables Ltd., which advises on renewable energy projects in Poland. “It made opposition to renewables quite difficult to justify because economically, it was very attractively priced.”

As 2020 approaches, the government’s stance on clean energy is starting to change. Clean air and green energy are two of five main topics that Law & Justice is addressing in its political campaign, while coal is barely mentioned.

Energy Minister Krzysztof Tchorzewski, a major proponent of coal power, has championed a 1 billion-zloty ($255 million) solar subsidy program. Additionally, the government plans to auction a record 3.4 gigawatts of renewable energy this year. The country’s photovoltaic capacity passed the 1 gigawatt mark on Oct. 1, up 158% from a year earlier, as households and enterprises sped up installations of solar panels.

Global investors have taken notice. Aberdeen Standard Investments has been buying up portfolios of Polish solar projects. And Macquarie Bank Ltd.’s Green Investment Group bought an onshore wind farm in the country earlier this year. Good wind resources, future government tenders and a market for corporate power purchase agreements make the country increasingly attractive, according to Mark Dooley, global head of the Green Investment Group.

“Renewables are going to have a rapidly growing presence there,” Dooley said in an interview. “It’s a meaningful opportunity.”

Trailing Targets

Still, Poland is seen as the black sheep of climate policy within the EU. In June, Morawiecki led a group that hindered the bloc’s push for zero net emissions by 2050 and the nation will almost certainly fall short of an EU target to get 15% of its electricity from renewables by 2020.

Arguing its case in the climate talks, the government repeatedly said that communism is to blame for its dependence on coal and maintains that it still needs the fuel to ensure energy security. The negotiation tactic is designed to bring billions of euros in subsidies from the EU, without which Poland won’t be able to speed up the coal exit, according to Tchorzewski, the energy minister.

Reaching zero emissions in the entire economy in 2050 is wishful thinking that would cost the country 900 billion euros ($992 billion), the minister has said.

“We love green energy, but electricity is most expensive when it’s not delivered,” Morawiecki said last month. “We need coal to ensure steady power supplies.”

--With assistance from Ewa Krukowska.

To contact the reporters on this story: Maciej Martewicz in Warsaw at mmartewicz@bloomberg.net;William Mathis in London at wmathis2@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Reed Landberg at landberg@bloomberg.net, Rob Verdonck, Andrew Reierson

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.