Dec 6, 2022

Poorest Nations’ Debt-Service Payments Surge 35% to $62 Billion

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- The world’s poorest nations saw their debt-service payments jump by about a third to more than $62 billion in 2022 from a year earlier, and these costs will keep diverting resources from health and education next year as interest on deferred repayments compounds, the World Bank said.

“The increased liquidity pressures in poor countries go hand in hand with solvency challenges, causing a debt overhang that is unsustainable for dozens of countries,” the lender said in its annual debt report published Tuesday.

Public debt reached record levels in rich and poor nations alike during the pandemic, with the global total of external debt climbing 5.6% to $9 trillion by the end of 2021 from a year earlier. For the most fragile countries, high fiscal and debt vulnerabilities have undermined economic stability.

“The debt crisis in the world’s poorest countries is intensifying,” World Bank President David Malpass said, repeating his view that the risk of stagflation - where prices increase and economic growth stalls - is climbing and that there could be a global recession next year. “It’s clear that this is a dire situation.”

The heads of the world’s biggest international finance institutions have long sounded the alarm about record global debt levels, particularly as monetary authorities have had to raise interest rates to quell accelerating inflation.

While the Group of 20 forum of nations allowed 48 poorer countries to defer $8.9 billion in repayments from May 2020 under the so-called Debt Service Suspension Initiative — freeing up funds to counter the effects of the Covid-19 pandemic — that reprieve ended in December last year.

“Payments scheduled for 2023 and 2024 are likely to remain elevated because of high interest rates, maturing principal, and the compounding of interest on Debt Service Suspension Initiative deferrals,” the World Bank said.

During the DSSI reprieve, the 48 countries still paid $99 billion in debt service — equal to about 4% of their combined average gross national income in 2020 and 2021, the bank said.

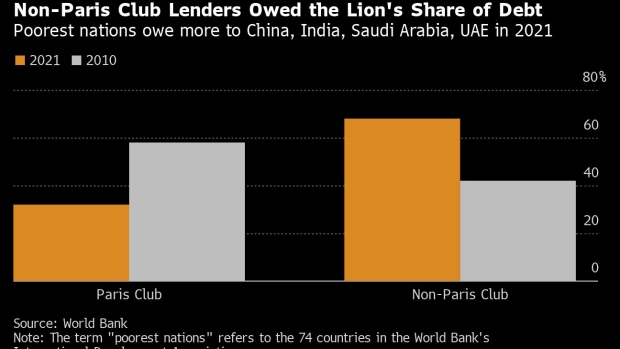

Debt owed by the world’s 74 poorest nations — who form part of the World Bank’s International Development Association — has more than quadrupled since 2010, Malpass said.

The IDA countries owed nations such as China, India, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates about $138.3 billion at the end of 2021. That’s more than double than what was due by them to the Paris Club of traditional rich debtor countries at $64.2 billion, the World Bank said.

China’s share of official bilateral debt stock grew from to 49% in 2021 from 18% in 2010, with debt-service flows to the country estimated at $17 billion in 2022 and accounting for 66% of official bilateral debt service, tha bank said.

Private creditors accounted for 61% of public and publicly guaranteed debt of low- and middle-income nations in 2021, up from 46% in 2010, the bank said.

With poor nations borrowing more from private creditors, the average terms of new-loan commitments have hardened: the average maturity on loans from private creditors during this period was 12 years, compared with 26 years for loans from official creditors, the bank said.

The average interest rate was 5%, or 3 percentage points higher than the average interest rate of 2% on loans from official creditors.

The bank found that highly indebted poor countries were able to diversify financing risks by having a more dispersed creditor base. In times of crisis, however, having more creditors would likely aggravate collective-action problems and burden sharing by creditors, leading to longer and more costly restructuring processes.

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.