Mar 22, 2021

Popeyes plots to become global power

, Bloomberg News

Some 18 months after its chicken sandwich went viral, fast-food chain Popeyes is on a mission to take over the world.

It may not work, of course. Its parent, Restaurant Brands International Inc., has a spotty overseas record, at best. But the ambition alone underscores just how startling a transformation the once-sleepy brand has undergone since the summer of 2019, when the launch of a seemingly ordinary sandwich—a piece of fried meat with pickles and mayo—ignited a frenzy that sparked long lines, sellouts and even fisticuffs all across America.

Whatever the reasons are that it took off like it did—and it's not clear that anyone truly knows—Restaurant Brands is aggressively seeking to cash in. Popeyes will debut in the U.K. this year, the company is expected to announce this week. That will expand its budding empire to about 30 countries, and Australia is also likely on the docket. Last week, it said a franchise partner would add hundreds of locations in Mexico.

The biggest prize, though, is China, where KFC is a cultural fixture as the country’s largest chain with more than 7,000 locations and three decades of experience. Popeyes opened its first restaurant there in May with a franchise partner and wants to reach 1,500 in a decade, which by itself would boost the chain’s locations by about 50 per cent.

“Customers love chicken in that part of the world,” Restaurant Brands Chief Executive Officer Jose Cil said in a recent interview. “We think there’s a huge opportunity for us by providing an alternative” to “the biggest chicken player in the world.”

The stakes are high for Cil. The company’s other brands, Burger King and Tim Hortons, have tried all kinds of strategies to ignite sales over the past few years and little has worked. Those brands have also struggled in the U.S. during the pandemic. By contrast, Popeyes, which Restaurant Brands acquired in 2017, grew 15 per cent last year.

Popeyes still has plenty of room to expand. Its 3,400 locations worldwide (KFC has seven times as many) generated US$556 million in sales last year, just 11 per cent of the company’s total revenue. And only a quarter of those eateries are outside America. Restaurant Brands mostly uses a franchise model that speeds up openings because it relies on finding partners, instead of building a local team. Since the chicken sandwich, Popeyes continues to be inundated by potential franchisees from “across the globe” said Cil, who got the CEO job in January 2019 after running Burger King for four years.

In today’s social-media age, consumer products regularly get caught up in memes and viral moments. Bernie Sanders’s coat, made by Burton Snowboards, grabbed attention at January’s presidential inauguration. Back in 2016, the “Damn, Daniel” craze boosted sales of white loafers from Vans, a brand owned by VF Corp.

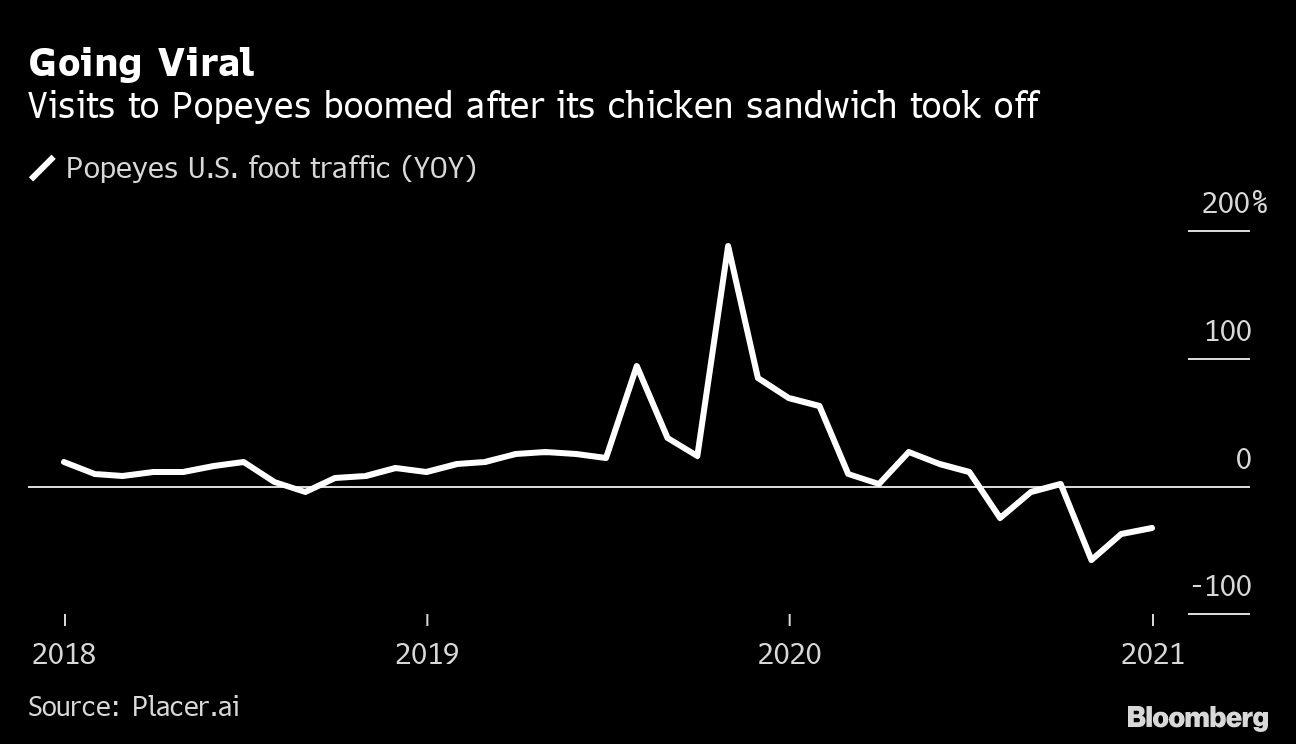

But those sales gains were fleeting in many cases. Restaurant Brands is making the bet that the sandwich marks a permanent change in the trajectory of Popeyes. And it’s easy to see why. In the year after the sandwich debuted, the average Popeyes franchise in the U.S. saw sales increase by US$400,000 to a total of US$1.8 million—almost a 30 per cent gain. That’s well above KFC, but not even half of what the average Chick-fil-A does, according to QSR Magazine, a trade publication. Foot traffic to Popeyes locations jumped by almost half in 2019 and then rose another 29 per cent in the first half of 2020 despite the COVID-19 pandemic, according to Placer.ai.

Then add the chicken boom. Worldwide, people are eating more poultry than ever. Global per capita consumption has increased more than threefold since the mid 1960s, according to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

Looking back, many have credited what has to be one of the world’s most valuable social media posts for starting this. In August 2019, Popeyes debuted the sandwich to rave reviews. About a week later, Chick-fil-A touted its version on Twitter as the original. A simple “y’all good?” reply from Popeyes ignited what the media soon dubbed the “chicken sandwich wars.”

Popeyes locations got quickly overwhelmed, and sold out in two weeks. It restocked, and the frenzy returned. All the while, news stories on those long lines kept America interested for months.

The summer of 2019 proved to be a crossover moment for Popeyes, pushing a brand with a big following in the Black community into new parts of America. The craze birthed stories in no less than the New Yorker and hundreds, if not thousands, of YouTube chefs tried making their own version of the sandwich.

Popeyes, founded in New Orleans in 1972, is taking this unexpected gift and expanding—from the Philippines to Spain. Cil rattled off a list of locales, like South Africa, that he wants to go after next.

Taking on KFC in China won’t be easy. Owner Yum China Holdings Inc., which licenses the brand from U.S.-based Yum! Brands, added 600 KFC locations in the country just last year. Knocking off such an entrenched market leader will take a lot of advertising, according to John Gordon, principal at Pacific Management Consulting Group, a restaurant consultancy.

“It’s always more difficult to come in and take market share away from the incumbent,” Gordon said.

KFC was also the first U.S. fast-food chain to enter China, arriving in 1987, and over the years has loaded its menu with local favorites, like shrimp burgers and congee. It’s evolved into much more of a sit-down experience that many Chinese consumers have viewed as a premium offering.

Sami Siddiqui, president of Popeyes in the Americas, points out that the chain’s debut in Shanghai brought a line of 2,000 people. It’s mostly a digital restaurant with six kiosks. And to cater to local tastes, the company added roasted chicken and more wings to the menu. It also tweaked the sandwich, swapping out breast meat for thighs, which are preferred in China.

“The chicken sandwich changed the game for us,” Siddiqui said in an interview. “We want to take that success to the rest of the world.”