Sep 18, 2019

Powell the ‘Artful Dodger’ Declines to Signal What Comes Next

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell doesn’t like to show his hand, either to guide investors or to chart a path for a divided group of policy makers under his leadership.

Powell, speaking after the U.S. central bank on Wednesday lowered interest rates for a second time this year, resisted several invitations during the press conference that followed to signal where he thinks rates should go in the remaining months of 2019. The chair also refused to say where he stands among officials split between those who see a need to cut further, others who are comfortable where rates are now and a group that didn’t favor easing at all.

Again and again he reverted to no-answer answers, saying he and his colleagues would take things “meeting-by-meeting,” that they “made one decision today,” and would “act as appropriate” in response to incoming data to keep the longest U.S. economic expansion on record from stumbling into the ditch.

The reaction in financial markets, where investors anticipate at least one more cut this year, was not severe. The yield on 10-year Treasuries rose about 4 basis points, while U.S. stocks erased earlier losses as equity investors drew confidence from Powell’s emphasis on the favorable U.S. economic outlook.

But Powell, in what’s becoming habit, once again left Fed watchers scratching their heads over what might come next.

“Jay is a no-guidance Fed chair, and from day one has operated on a principle of one decision today,” said Mark Spindel, chief investment officer at Potomac River Capital in Washington.

Grant Thornton’s chief economist Diane Swonk called him “the artful dodger” in a note to clients. “Powell dodged all questions regarding the course of rates going forward and where he sits on the spectrum of views on display” on the Federal Open Market Committee, she wrote.

Balance Sheet

Powell was also circumspect in answering questions on whether turmoil on money markets this week would push the Fed to resume purchasing assets to increase reserves on its balance sheet.

Powell told reporters the Fed officials have tools to relieve funding tightness, and they would be assessing when it will be appropriate to resume “the organic growth of our balance sheet.”

Some analysts are calling the resumption of balance sheet growth “QE-Lite” because it would involve the Fed purchasing bonds. Others warned that was a misnomer because it isn’t a monetary policy easing to bring down long-term interest rates. The Fed has traditionally grown its balance sheet to keep up with demand for currency as the economy expands.

No Obligation

Fed chairs are under no obligation to ease Wall Street’s uncertainties. Indeed, Alan Greenspan, who led the central bank from 1987 to 2006, made an art form of leaving his listeners confused. But the Fed has since embraced clear communication as a tool for effective policy making. Allow investors and the public to know how you’re thinking and they’ll be better equipped to understand your reaction to changing circumstances.

Adding irony to the situation, Powell himself took office pledging “plain English” as the new language of the Fed to the cheers of Wall Street, which had grown weary of former Fed Chair Janet Yellen’s more academic style of communication.

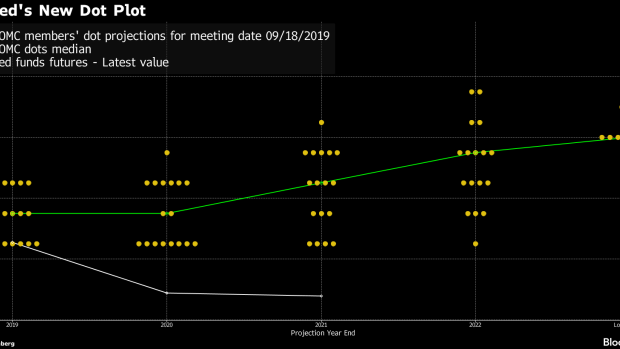

Today’s poker face was especially frustrating given the division among Fed officials. In their projections for where rates should fall at the end of 2019, the so-called “dot-plot” showed seven officials anticipated one more cut, five believed rates should now stay where they are and five felt rates had already dropped too far.

“The FOMC is about as divided as I have ever seen it,” Stephen Stanley, chief economist at Amherst Pierpont Securities, wrote to clients.

That led naturally to questions about where Powell stood, with opinions divided over whether he favored another cut or standing pat.

The committee was similarly divided in June, when Powell appeared to unintentionally reveal that his sympathies lay with a group of seven officials at the dovish end of the dot-plot, then favoring two more cuts this year. Assuming that group remained united, that would suggest Powell favors another quarter-point move down by December.

But other crumbs offered on Wednesday pointed to the chair possibly standing in the middle, waiting for additional data. Policy, he said, “will continue to be data dependent and data includes the evolving risk picture. That’s where I am and that’s where I think where the bulk of the committee is.”

Little Hint

If that was a hint, it wasn’t very strong.

Historically, when the committee is divided, it falls to the chair to signal the way forward. As Michael Gapen, chief U.S. economist at Barclays PLC, said: “There are times the chair has got to say, ‘I need you to get in line.’”

Powell has consistently declined to do this. That’s maddening for the markets but so far has not proved damaging.

“It provides potential for a muddied message and may make for more volatility from time to time,” said Gapen. “But it doesn’t reach the level where it’s a problem for the appropriate setting of policy.”

In Powell’s defense, these are also genuinely uncertain times. It’s no coincidence that officials at the European Central Bank were also sharply divided over its decision last week to cut rates there even further below zero and relaunch large-scale asset purchases.

“I don’t think there was a communication mistake,” said Priya Misra, global head of rates strategy at TD Securities USA. “He doesn’t know. He is non-committal and he is uncertain.”

--With assistance from Rich Miller and Steve Matthews.

To contact the reporters on this story: Christopher Condon in Washington at ccondon4@bloomberg.net;Craig Torres in Washington at ctorres3@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Alister Bull at abull7@bloomberg.net, Sarah McGregor

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.