Aug 23, 2019

Prince Harry’s Shaming Is Bad News for Private Jets

, Bloomberg News

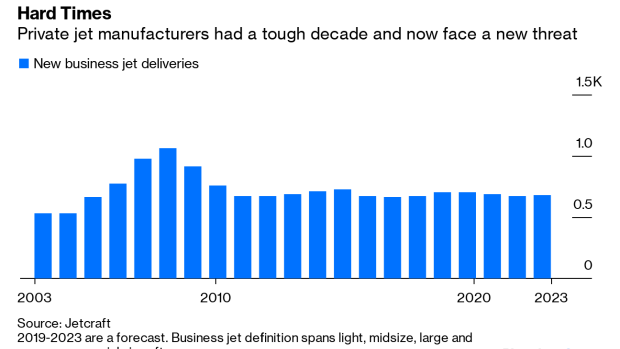

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Given the swelling ranks of the world’s billionaires, you’d have thought the past 10 years would have been fabulous for private jet suppliers.

In reality, the period since the great recession has been a “lost decade” for the industry’s manufacturers, analysts say. A glut of second-hand aircraft sapped demand for new models, while shared ownership and renting became popular alternatives to buying a plane outright. Meanwhile, large corporations that once thought nothing of jetting their execs around in comfort started scrutinizing budgets and worrying about conspicuous excess. In 2017 General Electric Co. said it would sell its fleet after unflattering reports about its former boss, Jeff “two planes” Immelt.

The industry seemed to have turned a corner recently thanks to the U.S. economic recovery, a fresh lineup of bigger models, plus tax giveaways from President Donald Trump that made it much cheaper to purchase a plane. North America is expected to account for more than half the global market for private jets in the next five years, according to Honeywell International Inc.

Yet suppliers face another looming threat: Our rapidly heating planet might make boarding a fuel-guzzling jet seem unconscionable. In Sweden there’s even a word for this new aversion to flying: flygskam or “flight shame.” Are the super-wealthy 1% susceptible too?

It’s not just climate campaigners who think the industry has an image problem. Warren East, chief executive of the jet engine-maker Rolls-Royce Holdings Plc, said recently that aviation as a whole “is built on setting fire to hydrocarbons” and needs to wean itself off that “quite quickly.” Bombardier Inc., owner of the Learjet brand, warned in its annual report that “the impact to us and our industry from legislation and increased regulation regarding climate change is likely to be adverse and could be significant.”

The globe-trotting business elite and A-list celebrities who once made private jets such desirable status symbols certainly aren’t helping the industry’s image problem, with the media increasingly taking issue with those who preach the environmentalist faith while turning up at events in their Gulfstreams.

The British royal Prince Harry has been dubbed the “Carbon Footprince” by his country’s press after taking several private flights to the Mediterranean this summer, despite his outspokenness on ecological issues. It’s doubly ironic that one of those journeys was to Alphabet Inc.’s four-day climate change summit in Sicily, where an epic queue of private jets rather undermined the well-intended activism.

You can see what the critics are getting at from a “do as I say, not what I do” perspective. Travelling by private jet produces several times more carbon dioxide than purchasing an economy seat on a commercial flight (precisely how much depends on how many people are on board and whether the jet flies home empty). The average American is responsible for about 16 tons of CO2 emissions per year. That’s already three times the global average, but it’s only a fraction of what private jets produce in a typical year.

As such, the tax advantages for private jets are very hard to justify. Nor is it helpful that many operators will be exempt from the aviation industry’s commitment – known as Corsia – to cap net emissions at 2020 levels and to halve these by 2050.(1)

Banning private jets, as some have suggested, wouldn’t do much to curb climate change as there are only about 20,000 of them operating today. The aviation industry accounts for about 2%-3% of global emissions and private jets perhaps pump out as little as 0.04% of the total, according to industry groups.

But symbolism matters in the climate debate. If private jet users aren’t seen to be doing their bit, they can’t reasonably expect poorer folk to make sacrifices either. While the purchase of carbon offsets to make up for the impact is worthy and rational, intellectual justifications are a hard sell on this topic.

Of course, private jets aren’t just frivolous toys, they have their uses too as a time-saving device for executives. As such, their users and makers will be eager to combat any burgeoning environmental backlash through the development of cleaner technologies. Carbon efficiency will no doubt become as important as time efficiency in selling planes.

Startups such as Eviation, as well as incumbent manufacturers and suppliers, are already plowing money into hybrid and electric aircraft. The industry is also trying to encourage operators to use non-petroleum fuels, although they’re expensive and hard to get hold of.

Because of the limited energy density of batteries, it’s probable that smaller aircraft will be the first to go electric. In the meantime, my guess is that rich folk will think twice before posting a shot of their plush planes on Instagram. The Swedes have a word for that too: smygflyga – or “flying in secret.”

(1) Planes with a maximum takeoff weight of below 5700kg and operatorswith fewerthan 10,000 tonnes of annual carbon emissions are excluded. The private jet industry says it will pursue voluntarily the same goals anyway.

To contact the author of this story: Chris Bryant at cbryant32@bloomberg.net

To contact the editor responsible for this story: James Boxell at jboxell@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Chris Bryant is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering industrial companies. He previously worked for the Financial Times.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.