Aug 1, 2020

Putin Challenged by Rising in the East That Kremlin Won’t Quell

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- Just a month after sealing a referendum victory that allows him to remain as Russia’s president until 2036, Vladimir Putin is suddenly facing the biggest protests against the government in years. So far, the Kremlin’s allowing them to happen.

Residents of the Far East city of Khabarovsk have taken to the streets in daily rallies sparked by the arrest of their popular local governor, Sergey Furgal, with numbers swelling into tens of thousands at weekends. They plan to march again on Saturday amid signs their anger is evolving into broader demands for Putin to step down.

“Nobody spoke about Putin” at first, said Kristina, 35, a manager in Khabarovsk who’s taken part in the protests and declined to give her last name. “Now as the demonstrations have grown, it’s ‘freedom for Furgal and goodbye Putin’. It gets bolder every Saturday.”

Still, despite concern in Moscow, the authorities have no plans to crush the demonstrations, said two officials involved in Kremlin efforts to defuse the situation. The use of force against tens of thousands of people could provoke an even bigger political crisis, one of them said.

The Khabarovsk rallies are the largest sustained anti-government demonstrations since 2011-2012 protests in Moscow that ended with a harsh Kremlin crackdown. The challenge to Putin’s authority thousands of miles from the capital comes after he claimed overwhelming approval in the July 1 referendum for constitutional changes that give him the right to seek two more six-year terms after his present one expires in 2024.

Kremlin spokesman Dmitry Peskov didn’t immediately respond to a request to comment. “The situation will calm down” as the new leadership in Khabarovsk gets down to work, he told reporters on a July 29 conference call. “We hope so.”

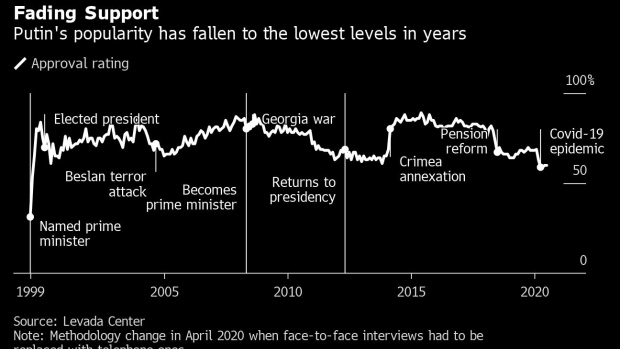

In power since 2000, Putin, 67, has seen his popularity tumble to a record low amid an economic slump sparked by the coronavirus pandemic and a plunge in the price of oil, Russia’s main export earner.

With the protests attracting up to 60,000 or more in a city of 600,000, “the authorities can’t round up one in ten people,” said Natalya Zubarevich, head of regional studies at Moscow’s Independent Institute for Social Policy. “People across the country are watching with interest because Khabarovsk is an example of how to stand up for your rights.”

The show of defiance has spread to other parts of the Russian Far East including the Pacific port city of Vladivostok, where protesters have declared support for the Khabarovsk marchers.

There’s evidence of wider sympathy too. A July 24-25 survey of 1,617 Russians by the independent Levada Center found that 45% viewed the protests favorably and 29% said they were willing to join similar actions in their own regions.

Though discontent is widespread in Russia, Furgal isn’t a figure who’s attracted much support nationally and there’s no sign of any groundswell in his favor. State television has given little coverage to the protests and has played down the numbers in attendance.

While riot police routinely break up unauthorized protests in Moscow, officials in Khabarovsk have refrained from any crackdown on the rallies so far. Police were even seen handing out masks to participants as protection from Covid-19.

Investigators detained Furgal on July 9 and flew him to Moscow over allegations he organized several murders in 2004-2005. He denies the accusations.Furgal, who’s from the nationalist Liberal Democratic Party, won a shock victory against the ruling United Russia candidate in 2018 amid a voter backlash over an unpopular pension reform advocated by Putin. He also earned local support for his moves to limit officials’ privileges and bolster social assistance.In Khabarovsk and much of Russia’s Far East, there’s particular unhappiness at a lack of investment and job support that’s seen as a reflection of Moscow ignoring the region’s interests, said Zubarevich.

State-run gas company Gazprom employs cheap migrant labor on major projects rather than local workers, for example, while the managers employed by headquarters earn international wages, according to Valentina Kupriyanova, a political expert in Khabarovsk.

Strong Tradition

There’s a strong tradition of protest in Khabarovsk and other areas near the border with China because people feel far away from Moscow and have an independent frontier mentality, she said.

Furgal was unusual for a Russian governor because he behaved like a genuine politician rather than a bureacrat, said Alexei Makarkin, deputy director of the Center for Political Technologies in Moscow. The Kremlin’s appointment of a temporary replacement, Mikhail Degtyarev, who’s from the same party as Furgal but has no local roots, only poured fuel on the flames.“The authorities assumed at first people would stop protesting, but they’re still on the streets.” Makarkin said. Police “aren’t dispersing them because their own relatives are there on the square,” while the Kremlin risks sparking clashes with local law enforcement if it sends in riot troops from Moscow, he said.

“Khabarovsk is a problem,” Gleb Pavlovsky, an ex-Kremlin adviser, told Echo Moskvy radio. “There’s a new level of distrust toward Moscow, toward Putin, toward the central government, and all this has fused into one.”

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.