Apr 24, 2019

Rates Traders May Be Thinking of a 1998-Style Fed Rate Reduction

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- Bond traders are gaining confidence that the Federal Reserve will see prevention as the best medicine, in an echo of its policy prescriptions from two decades ago.

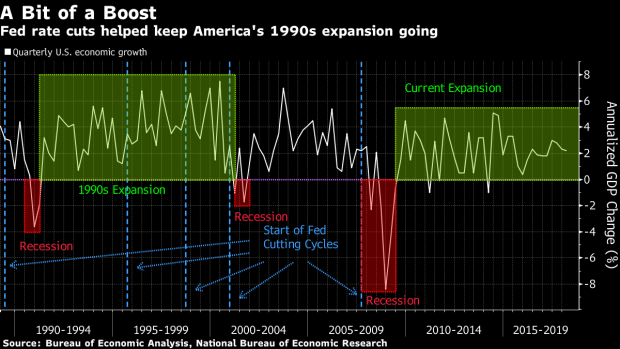

The futures market is moving back toward pricing in a full quarter-point Federal Reserve rate cut this year, even as U.S. and Chinese economic data show signs of improvement and American stocks rally to record highs. Luke Tilley of Wilmington Trust Investment Advisors and strategists at BMO Capital Markets interpret that as a sign the market has 1998 on its mind: That’s when the central bank pre-emptively lowered rates to keep events abroad from pushing the U.S. into recession.

The global economic backdrop was darker back then, given the Asian financial crisis, Russia’s debt default and the near-collapse of hedge fund Long-Term Capital Management. But other aspects of 1998 seem eerily similar to today, say Tilley and BMO’s Jon Hill. The U.S. economy was humming along, inflation was low, and the S&P 500 Index was at or near a record. When the Fed cut rates that year, it kept the longest postwar U.S. expansion going.

“You have to pay respect to what the market is pricing in,” said Brett Wander, who oversees $28.7 billion as chief investment officer for fixed income at Charles Schwab Investment Management. “A rate cut is a scenario that people have got to consider, even if it’s not the most likely scenario.”

Headwinds Abound

Though angst over the world’s two largest economies has eased, other areas of concern remain. The growth outlook is bleak in Europe. Japan remains mired in a deflationary mindset. And Wednesday brought a dovish policy statement from the Bank of Canada and a report of slowing inflation in Australia. Traders boosted rate-cut expectations for both economies.

Meanwhile, inflation in the U.S. has been mostly stuck below the Fed’s 2 percent target for seven years. Low or decelerating inflation could trigger a rate cut because it would be seen as a sign that rates are too high, notwithstanding higher oil prices that could have only a temporary or distorting effect on the data, BMO’s Hill said.

The Fed’s 1998 cuts received renewed attention in March when Fed Vice Chair Richard Clarida and Chicago Fed President Charles Evans mentioned them as examples of how global shocks spurred U.S. policy action.

Challenging Notion

Their remarks were a step toward grasping the “very challenging” idea of why the Fed would lower rates in the absence of a domestic economic downturn, said Tilley, a former Philadelphia Fed adviser who sits on the investment committee of Wilmington Trust, which manages $89.1 billion.

For Wander, stocks may dictate whether the Fed shifts to easing mode. A dive in equities along the lines of the magnitude seen in the fourth quarter would be enough to push policy makers toward a cut, he said. An easing is one possible scenario currently being factored into Schwab’s investment strategy, he said.

To be sure, policy makers have less room to cut rates than in 1998. If the Fed halts the tightening cycle that it began in December 2015, that would leave the target for the benchmark U.S. rate at 2.25 percent to 2.5 percent, compared with 5.5 percent right before the first 1998 rate cut.

Market Signals

But some corners of the bond market are boosting wagers on a Fed rate cut. The closely watched spread between 2- and 10-year Treasury rates is resteepening. And in eurodollars, there’s been a burst of demand this week for hedges against rate cuts as soon as this year.

The possibility of a reduction can’t be dismissed even if the base-case scenario is for the central bank to be on hold all year, according to Wander and BMO’s Hill. Hill sees a small chance of a “fine-tuning” rate reduction or a few successive cuts, a move that he says would be hard to pull off without triggering expectations of a full-on multi-year easing cycle. Gains in stocks may have reduced the likelihood of such a shift, Hill said.

Policy makers delivered three quarter-point cuts from September to November 1998, bringing the fed funds rate down to 4.75 percent. In that episode, the central bank actively re-steepened the yield curve after it had inverted earlier that year, likely buying itself more time and extending the economic cycle, according to Tilley.

A persistently inverted curve, historically seen as a harbinger of recession, is the only condition he sees now that, by itself, could cause the Fed to cut rates. Wilmington Trust’s base case, though, is for the Fed’s next move to be a hike in 2019 or 2020. Wilmington Trust is largely staying put since its portfolios are overweight large-cap U.S. stocks, which Tilley says should do well if the Fed does lower rates.

The U.S. has had only three recessions in the past three decades, giving policy makers “few data points to work with,” and making the experience of 1998 especially relevant, Tilley said. The central bank “has a long institutional memory.”

--With assistance from Edward Bolingbroke and Steve Matthews.

To contact the reporter on this story: Vivien Lou Chen in San Francisco at vchen1@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Benjamin Purvis at bpurvis@bloomberg.net, Mark Tannenbaum, Nick Baker

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.