Dec 9, 2021

RBA’s Harper Sees Economy Running Hot Without Runaway Inflation

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- Australia’s economy can run hot while dodging the runaway inflation that’s plaguing much of the world, said Reserve Bank board member Ian Harper, signaling monetary policy will stay ultra-loose for some time yet.

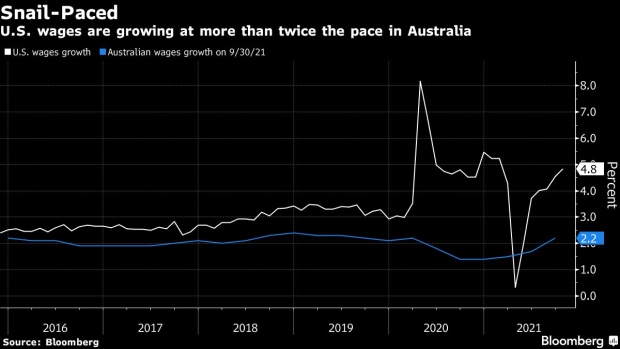

Harper cited Australia’s relatively resilient workforce participation during the pandemic, in contrast with trends seen overseas such as mass resignations and people quitting the labor force. He said that was a key reason why Australian unemployment will take time to fall to levels needed to spark strong wages growth and subsequent price pressures.

“With a strong recovery in labor force participation, the likelihood of there being a breakout in wages is very low,” Harper, who’s also dean of the Melbourne Business School, said in an interview. “What’s been amazing is that even with the borders closed we can run this economy quite strongly without producing inflation.”

While Harper wasn’t speaking on behalf of the RBA, his views chime with those of Governor Philip Lowe, who has repeatedly said wages growth of “3 point something” is needed to push inflation sustainably within the bank’s 2-3% target band from 2.1% now. The RBA has maintained its dovish stance on inflation despite data showing a strong economic rebound is underway following harsh lockdowns this year along the country’s east coast.

Similar growth surges have been seen in major economies, but often accompanied by soaring inflation as lockdowns eased and rampant consumer demand blindsided producers of goods and services. While the RBA’s preferred measure is underlying inflation, the consumer price index grew 3% in the third quarter, far lower than the U.K.’s 4.2% in October and U.S. annual rate of 6.2%.

The RBA has left interest rates at a record low 0.1% since November 2020 and Lowe has pledged not to tighten policy until actual, not forecast, inflation is well within range. The bank doesn’t see that happening until late 2023, a doggedly dovish outlook compared to financial markets which are pricing in three rate increases next year.

In explaining why inflation was unlikely to run hot in Australia, Harper cited the example of Western Australia. The state has closed its domestic and international borders in a bid to keep Covid-19 from its shores, and is still not seeing signs of strong wages growth. Unemployment there is at 3.9% compared with the national rate of 5.2%.

“So we have a natural experiment that looks like the Australian economy is running with much lower levels of unemployment than people had experienced before, without actually producing a burst of wages growth and leading onto a burst of inflation,” Harper said.

“That is something that really does distinguish us from experiences elsewhere. And it’s another reason why various people, myself included, don’t think that we are on the cusp of runaway inflation.”

In Australia, labor force participation has hovered around 65-66%, largely driven by government support payments that allowed businesses to keep staff on their books even during lockdowns. That compares with 61.8% in the U.S., from a high of 63.4% before the pandemic, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Stronger-than-expected economic growth contributed to the RBA abruptly dropping its yield target last month. At its next board meeting in February, the central bank will review its A$4 billion ($2.9 billion) per week bond-buying plan. Economists expect it to further taper or drop the program altogether.

Harper didn’t comment on the path of monetary policy, but said there were reasons to believe that wages growth will pick up sooner rather than later. He was optimistic on Australia’s economic growth, citing an upbeat outlook for the corporate sector with both business investment and credit on the rise.

The latest official estimate of business investment and intentions showed firms upgraded their capex plans for the current financial year to the best since the mining investment boom ended in 2012. Crucially, non-mining spending is seen rising by 16% from a year ago, the strongest gain since 2000, led by a surge in demand and services.

“That’s very encouraging,” Harper said. “It looks like the business community is working through the impact of the pandemic.”

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.