Mar 16, 2023

Recession Fears Soar as Credit Suisse Woes Threaten Loan Crunch

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- An escalating crisis of confidence in Credit Suisse Group AG, a giant lender deeply enmeshed in the global financial system, is raising the risk of a bank-lending crunch that could tip economies into recession.

Coming days after the failure of three US banks, the latest bout of market turmoil threatens to rewrite the global outlook. The risk is that lenders will now be far more concerned with shoring up their own finances than providing the loans that enable economies to grow — even without a system-threatening bank collapse.

Before the past week’s dramatic shift, the big question was whether the Federal Reserve and other central banks could pull off a “soft landing” — where high interest rates manage to cool inflation without stalling growth — and the general view was that tighter money hadn’t actually hurt economies all that much. But the prospect of a banking crisis has upended that narrative.

‘Financial Accident’

“A financial accident has happened, and we are going from no landing to a hard landing driven by tighter credit conditions,” said Torsten Slok, Apollo Global Management’s chief economist, in a note to clients Wednesday.

Goldman Sachs Group Inc. economists led by Jan Hatzius have boosted their estimate of the odds of a US recession to 35% over the next 12 months in response to increased uncertainty over the economic impact of bank stress.

One measure of the pivot: investors have been abandoning bets on more inflation-busting rate hikes by central banks — and now expect them to be deploying the recession-fighting tool of rate cuts before long.

There was some reprieve in Asian trading Thursday. European and US equity futures advanced, Asian stocks pared losses and Treasuries fell after Credit Suisse said it would borrow money from Switzerland’s central bank and seek to repurchase debt.

Credit Suisse Taps Central Bank for $54 Billion to Stem Crisis

The unwinding of bets on central bank tightening isn’t because inflation has faded: it clocked 6% in the US last month, and has been running even higher in Europe. Even so, interest-rate futures suggest a diminishing chance of the Fed raising its benchmark by a quarter point next week, and point to cuts as early as this summer.

The European Central Bank is also seen scaling back rate hikes at its meeting Thursday.

“While letting inflation run might be bad, presiding over a credit crunch would be worse,” wrote economists at Pictet Wealth Management.

But the latter could happen anyway, whatever the central banks now do, some analysts are warning.

‘Cracks Form’

The Fed and its peers already raised rates at the steepest pace in decades to curb the post-Covid wave of inflation, but there were various forces limiting the immediate impact on economies. In the US, for example, households built up more than $1 trillion of extra savings in the pandemic, and they benefited from low fixed interest rates on mortgages and other debt. Pent-up demand for services and continuing labor shortages have propelled wage pressures.

Now, “you’re seeing cracks form, you’re seeing the liquidity and perhaps solvency of the banking system come under a lot of pressure,” said Bob Michele, chief investment officer at JPM Asset Management, on Bloomberg Television. “That’s going to cause businesses and consumers to pull back,” he said, concluding that a recession is “inevitable.”

“There’s credit tightening going on at every single level,” said Michele, whose career stretches back to the 1980s US savings-and-loan crisis. One potential area of vulnerability he sees is in commercial real estate, where offices have yet to return to full staffing levels after the pandemic— raising questions about property values in central business districts.

What Bloomberg Economics Says...

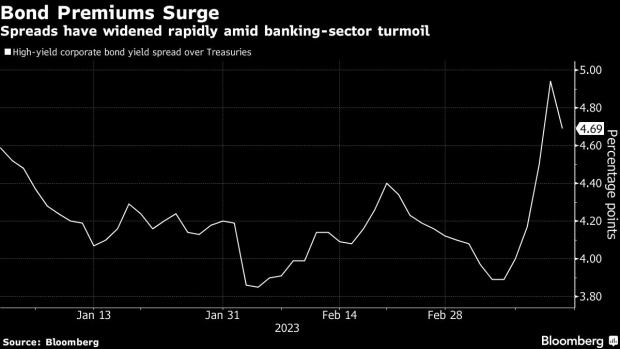

“We are still inclined for 25 basis points” for the March 22 Fed policy move. “One of the most important channels of financial-market distress to the real economy is through credit spreads, and, so far, it has not increased to a degree that would imply a significant slowdown in the economy.”

— Anna Wong, chief US economist.

The ground-shift in the US banking system has seen a flight of cash toward the biggest lenders since the weekend collapse of Silicon Valley Bank. One example: Bank of America Corp. has mopped up more than $15 billion in new deposits in a matter of days.

Read More: BofA Gets More Than $15 Billion in Deposits After SVB Fails

With funds moving away from regional lenders, the risk is that they’ll pull back on lending to their clients.

“Small and medium-sized banks play an important role in the US economy,” Goldman Sachs economists Manuel Abecasis and David Mericle wrote in a note to clients. They estimate that banks with less than $250 billion in assets make up:

- Roughly 50% of US commercial and industrial lending

- Some 60% of residential real estate lending

- 80% of commercial real estate lending

- And 45% of consumer lending

“The incremental tightening in lending standards that we expect from small bank stress would have the same impact on growth as roughly 25-50 basis points of rate hikes would have,” the Goldman duo wrote. They estimate that tighter financial conditions could shave half a percentage point off US growth this year.

JPMorgan Chase & Co. estimates the US economy faces a potential hit to gross domestic product of a half to a full percentage point from diminished credit growth in the aftermath of the latest banking-sector troubles.

Smaller and regional US banks account for a disproportionate share of lending, and if growth in their aggregate portfolio fell to zero — compared with the recent annual pace of $500 billion — that cut to GDP would be realized over about a year, JPMorgan economist Michael Feroli wrote Wednesday.

‘Canary in the Coal Mine’

The worst outcome for economies would be a giant bank failure: a lender as big as Credit Suisse serves as a counterparty to other banks on countless financial instruments. The US Treasury is actively reviewing the US financial sector’s exposure to the bank, Bloomberg reported Wednesday.

Policymakers at the US Treasury and elsewhere, who are closely monitoring the Swiss lender’s fate, have argued that regulatory changes since then have made the banking system much stronger.

The collapsed US lenders, like SVB and Signature, didn’t fall into the “systemically important” category, and they had idiosyncratic problems — investment in lower-yielding long-term bonds and in crypto assets, respectively. Even so, their failures have prompted a dramatic reassessment of the entire financial sector that’s likely to have effects reaching deep into the economy.

“This bank failure is a ‘canary in the coal mine,’” Bridgewater Associates founder Ray Dalio wrote in a newsletter on Tuesday, referring to SVB. It’s an “early-sign dynamic that will have knock-on effects in the venture world and well beyond it.”

--With assistance from Jonathan Ferro.

(Updates with Goldman’s view on recession risks in fifth paragraph, Asian trading in seventh paragraph and JPMorgan estimates lower down.)

©2023 Bloomberg L.P.