May 20, 2022

Recycling Isn’t Going to Solve Plastic Waste. Enter Windex

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- SC Johnson developed what seemed like an easy way to cut back on plastic waste when it released a concentrated Windex more than a decade ago.

Shoppers just had to pour the blue liquid from a pouch into a spray bottle, add water and go wipe down their bathroom mirror. Turning the popular glass cleaner into a concentrate meant using 90% less plastic. It also cut production costs and emissions from shipping a product mostly composed of water.

But shoppers and retailers ignored it. The closely held consumer goods giant attempted to sell it on its own website, but that didn’t work either.

“We tried a lot of different ways to make that successful,” SC Johnson Chief Executive Officer Fisk Johnson said of the company his great-great-grandfather founded in 1886. “We could never make a go of it.”

A decade later, the term “single-use plastic” has gone mainstream. Governments are banning plastic bags and straws. Startups are pressuring the industry by winning over consumers with refillable shampoos. Investors are increasing calls for companies to improve their environmental records.

And a revamped version of concentrated Windex released last month is at Target and Amazon.

“We’re at a real inflection point,” said Johnson, who also oversaw the debut of refill options for two other top brands, Scrubbing Bubbles and Fantastik. “The plastic waste crisis has become much more top of mind.”

For this to become more than an inflection point, a lot still needs to happen, though.

The industry must convince shoppers that adding water to a concentrate or bringing empty bottles to a refill station is worth it. That could be difficult because most options don’t offer big savings yet. And the pitch on helping the planet is muddied by the widespread belief that recycling is the answer to plastic waste — it’s not.

The recycling boom of the past twenty years — mostly funded by the plastics industry — created a false impression that consumption wasn’t a problem. However, only 9% of global plastic packaging is recycled, according to a report by the OECD. Meanwhile, annual production has doubled this century to almost half a billion tons.

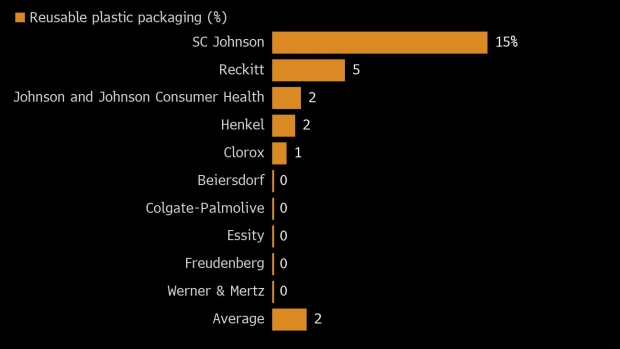

Companies are giving the issue more attention, but change has been slow. About a dozen large household and personal care manufacturers joined a pact created by the Ellen MacArthur Foundation to cut back on waste. Yet on average, only 2% of their total plastic packaging was designed for reuse. (SC Johnson led the group at 15%.) The upfront cost of reconfiguring products and factories is a hurdle. Another worry is that removing the ease of single-use options will depress sales.

Reusable packaging was once prevalent in the U.S. Take milk, which used to come in glass bottles that were later picked up, cleaned and refilled. But that model faded as cheap plastics gained ground.

However, refillables are staging a comeback as awareness about pollution and global warming increases. About three-fourths of plastic production between 1950 and 2017 became waste, according to the United Nations. Oceans and landfills are awash with the stuff, and even human blood shows traces of it. The carbon footprint of manufacturing plastics also generates emissions, accounting for 4.5% of global greenhouse gases in 2015.

Now more governments are taking action. France passed a law mandating a 20% reduction in single-use plastics by 2025 that requires at least half of the goal to be met with reuse. Maine and Oregon adopted regulation imposing levies on companies based on how much plastic they employ, with the money earmarked for funding recycling programs.

In March, 175 countries began talks at the United Nations to create a legally-binding treaty to end plastic pollution in what could lead to the most important green deal since the landmark Paris Agreement.

“Government regulation is going to be critical to solving this,” said Johnson, who supports laws like the ones passed by Maine and Oregon.

Companies are responding as the business case becomes more attractive. Selling concentrates and offering refills can reduce packaging and shipping costs. That’s especially compelling with the price of plastic and other inputs surging during the pandemic.

Launches of beauty and personal care products claiming to be reusable increased 35% from June 2020 to May 2021, according to researcher Mintel. Big brands are trying several models to see what sticks with consumers. In the US, Clorox offers tiny bottles of concentrate for its multi-purpose cleaner. Unilever sells refills for its OMO laundry detergent in South America. In Brazil, a third of consumers who normally bought the 3-liter single-use option have switched to the concentrate, the company said.

Target debuted a program in March to spotlight brands that cut back on packaging waste. On a recent visit to a Manhattan store, a display featured two dozen products touted as less wasteful, including a deodorant sold in a recyclable paper tube. In a different section, SC Johnson’s concentrates advertised a 94% reduction in plastic.

“Compared to three, four years ago, there’s definitely way more attention going into reuse as part of the solution,” said Sander Defruyt, the leader of the MacArthur Foundation’s plastics initiative.

The marketing approaches from many big brands have so far focused on selling the same product while helping the planet. Unilever pitches a body wash it turned into a concentrate as the “moisturizing Dove care you love,” while making it easy to reduce plastic waste.

But is that enough? History shows that green alternatives usually struggle to reach beyond the eco-conscious. The bar is even higher with refillable bottles because consumers are being asked to do more work. Blueland, a New York-based startup that’s raised $35 million, also goes after price, highlighting that its concentrated toilet cleaner cost about a buck.

SC Johnson doesn’t market its concentrates as money savers because it’s not yet a compelling case. A look at retail prices shows that a dissolvable pod is cheaper by less than 2 cents per ounce than the original in the plastic bottle.

“It’s going to take scale and economies of scale to get the cost in a situation where we can offer a refill at significantly lower cost to the consumer,” Johnson said. That “will help a lot.”

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.