Jun 20, 2021

Remembrance of Bonds Past: 8% Coupons, Real Inflation and No QE

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- Jim Leaviss is lamenting an unusual loss at work. Not the retirement of a colleague, but a bond that’s tracked his career through booms and recessions, economic upheavals and a paradigm shift in government debt markets.

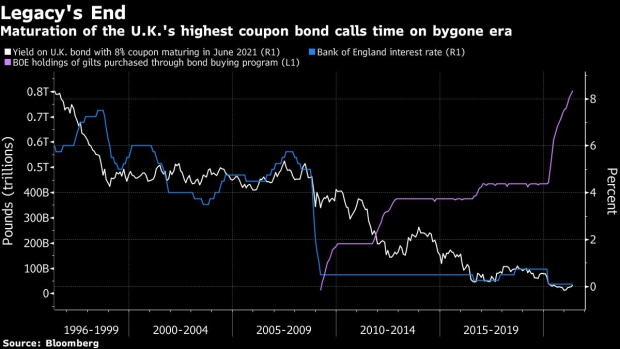

The U.K. gilt -- which matured this month -- was issued in 1996 with an 8% semi-annual coupon. Leaviss worked at the Bank of England at the time, and departed to manage bond funds for M&G Investments in 1997, going straight from the institution issuing the gilt to one buying it.

Its demise has got him feeling Proustian, he says, throwing him back to 1990s bond markets, where double-digit yields were normal and inflation was seen as more than just transitory.

It’s not just a U.K. phenomenon; legacy bonds from the 20th century are nearing their retirement elsewhere, too. In the U.S., the Treasury with the highest coupon -- 8.125% -- expires in August. Nowadays, some countries sell 0% coupon debt, with nominal yields in negative territory. Once you factor in inflation, fixed-income investors generally expect to lose money by holding developed-market government bonds to maturity.

“There aren’t many emerging-markets that give you 8% yield nowadays,” said Leaviss, who is now M&G’s chief investment officer of public fixed income. “If you’re under 30, this low-rates regime has effectively been your entire life.”

Since the 8% gilt was issued, it’s been a witness to monumental changes in how investing and government financing works.

The bond was barely a year old when the BOE was granted monetary policy independence. Its early teens coincided with the global financial crisis, putting British finances under tremendous strain, leading to years of austerity and cementing a low-rates environment. And in its later years, there was Brexit and the ensuing market swings, followed by a global pandemic.

The bond has barely traded in recent years, with 70% of the outstanding stock owned by the BOE since 2011 under its quantitative easing asset-purchase program.

Even more telling is the price at which the bond traded toward the end. It started off with a yield-to-maturity above 8%, yet began last year with a negative yield -- a once-alien concept that has now become almost a standard feature in developed government bond markets.

“Where we have held the bond in benchmark weight I would always try to avoid selling it or going underweight, such is the difficulty getting it back in the open market,” said Aaron Rock, a fund manager at Aberdeen Standard, who was in school when the bond was first issued. “It’s the end of an era to see a gilt with an 8% coupon disappear.”

Reflation Trade

Inflation concerns have crept back into the market this year as economies reopen and commodities boom, and one bond market measure is at its highest since 2008.

But many investors, as well as major central bank chiefs, ultimately see the current price pressures as transitory, derived in part from pent-up demand. That’s reflected in yields that, from a historical perspective, are still around rock-bottom levels. U.S. 10-year yields are about 1.5%, a quarter of their 1990s average, and the U.K. equivalent is below 1%.

And the 8% bond is a reminder that economies have changed dramatically this century.

“The historic experience of inflation over the last twenty years has been very different indeed from the start of my career,” said David Parkinson, sterling rates product manager at RBC Capital Markets, who sees inflation remaining under control. “The market has been conditioned over a considerable period of time that low and stable inflation is the norm.”

Beyond the dramatic change in rates, market veterans also remember a more disorderly trading scene. The U.K.’s Debt Management Office -- the institution created to issue debt after the BOE became independent -- currently runs a well-flagged schedule. But before its creation there was no pre-announced calendar, and Parkinson recalls the BOE selling gilts in the middle of the night as the 1992 election results came in.

There was also a swathe of different bond structures, from convertible gilts that could be transformed into a longer maturity at a predetermined price, to dual-date issues which could be redeemed between two specified dates.

Some had affectionate nicknames, such as the “Maggie Mays,” inflation-linked securities that could be converted to conventional gilts -- an option taken by investors after Margaret Thatcher won the 1983 election as she was seen as being more capable of getting inflation under control.

For many now, the biggest issue is the outsize impact of central banks on bond trading.

“As QE has gone on and more of the market has been owned by the BOE, that’s detracted from active management,” said Russ Oxley, a former money manager who bought bonds for Ignis and Old Mutual Global Investors over a two-decade career.

For RBC’s Parkinson, who started his career in 1988, the bond’s expiry offered a welcome trip down memory lane, though ultimately he thinks the current set-up is superior. It may be a more sanitized trading experience, but any loss of color is outweighed by the societal benefits of a better-functioning market.

“The gilt market now has the depth and flexibility that allows the U.K. to fund very substantial spending,” he said, pointing to funds needed to finance the pandemic furlough program. “It’s less quirky and unpredictable but there’s still never a dull moment and the changes I’ve seen generally have been positive.”

Next Week

- The main policy event is Thursday’s Bank of England rate decision, and investors will be seeking clues on the outlook for interest rates after the Fed’s hawkish pivot

- European government bond supply will see Germany, Italy and the Netherlands sell about 10 billion euros of debt ($11.9 billion), according to Citigroup Inc.

- The U.K. will sell 400 million pounds of inflation-linked notes maturing in 2065

- ECB President Christine Lagarde appears at the European Parliament on Monday; Olli Rehn, Luis de Guindos, Fabio Panetta, Isabel Schnabel and Pablo Hernandez de Cos all speak later in the week

- Data is focused on manufacturing and services PMI from the euro area, Germany, France and the U.K. on Wednesday; Germany releases Ifo numbers on Thursday

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.