Jul 14, 2022

Renewable Energy Provides Relief From Rising Power Prices

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- The summer of 2022 has not been a stable season for global energy. Fossil fuel supplies are short, demand is skyrocketing thanks to heat waves, and the worst may be yet to come, the International Energy Agency said this week. Some events may be localized, but global supply and demand brings challenges –potentially crises – to the entire world.

Renewable power is not exempt from global trends that are pressuring prices upwards. Thanks to inflation and supply-chain challenges, the cost of building new onshore wind farms has risen 7% in the past year. Solar costs have risen twice as much; battery storage costs have risen more than 8%. The resulting price of power from a new wind or solar project built today has risen to 2019 levels, a reversal in a decade-long trend of decreasing costs of electricity from wind and solar power.

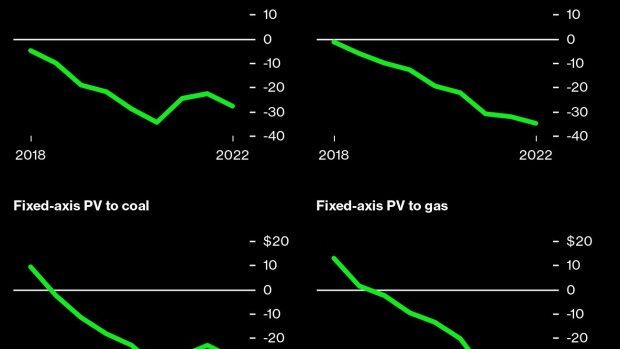

But at the same time, renewable power could provide some relief from rising power prices. Absolute cost figures are important, but perhaps more important are the details of the power markets in which new wind and solar projects operate. Onshore wind and solar costs have risen year on year At the same time, the cost of power from coal and gas have risen even more. The result is that the gap in between wind and solar (generally the lowest-cost options in most developed grids) and coal and gas has widened, not closed. The gaps between wind and solar, and coal-fired power, are greater than a year ago but still not as big as in 2020. The gaps between wind and solar, and gas-fired power, have never been greater.

While onshore wind and solar levelized costs have risen, the cost of offshore wind has fallen. In 2014, the benchmark cost of offshore wind power was more than double the cost of gas-fired power. Today, it is just 7% higher. Electricity system planners and power utility executives, if they expect fuel prices to be high in the future, may look at this narrow differential and plan in favor of the technology without any fuel costs (more on that in a bit).

Supply chain pressures are still very real, and companies feel them acutely, but one key indicator at least is much less acute than it was earlier this year. The cost of shipping one container from Shanghai to Rotterdam, a proxy for Asia-to-Europe routes that a great deal of power equipment would take en route to projects, has dropped from almost $15,000 to less than $10,000 since October 2021. Those rates, however, are still four times where they were pre-pandemic!

Inflation is certainly running hot, with the June Consumer Price Index rising 9.1% from a year earlier, a rate not seen since 1981. Inflation expectations, however, have softened significantly. The US five-year breakeven inflation rate, which indicates the inflation rate that market participants expect in five years’ time, has dropped by more than a percent since April. That does not mean that inflation is disappearing right now, but rather that the market does not expect today’s levels to persist in the future.

There is the theory of what a global energy cost modeling exercise indicates, and there is the practice of what energy market participants have committed to do. The UK’s latest renewable energy auction, in which developers of renewable energy projects offer their lowest feasible prices for selling power in the future, is the clearest indication we have that the industry expects lower costs.

The auction was the biggest ever, awarding 10.8 gigawatts of contracts, with more than half of the total volume going to offshore wind. Offshore wind also came in at the lowest bid prices for the first time, below onshore wind and solar. Offshore wind’s low price of £37.35 ($44.61) per megawatt-hour is about one-quarter the current UK day-ahead power price, when adjusted for inflation.

The big utility and project development companies, which won the UK auction with these record prices, did so thanks to several factors. Large scale is one — the average project size, 1.4 gigawatts, is bigger than the world’s biggest offshore wind project currently under construction. With scale comes greater purchasing power for equipment, and greater operational efficiency. Time is another factor. Developers have until 2027 to bring these projects online.

Finally, the UK auction results also indicate that offshore wind developers see opportunity even in very volatile markets. Historically, offshore wind projects would sell all of their power via a fixed 15-year contract. This time around, a few UK developers secured only part of their power purchases on a fixed 15-year contract, opting to sell the rest via private contracts directly with large customers, or directly to the wholesale power market. These strategies serve three purposes.

First, they help the country hedge against high wholesale prices for fifteen years. Second, they can soften the blow of high (and volatile) prices for large customers capable of locking in long-term fixed wind power prices. Lastly, they allow developers some upside too, where they are willing to take risks on the shape of the power market in the future.

Today’s markets are fraught with challenges and risks, and consumers worldwide are feeling the impacts of rising energy prices in overall inflation. Renewable power prices are rising along with all energy prices, while still being the lowest-price option in most markets, with the ability to lock in those prices for years. Locked-in low costs, with no carbon dioxide emissions, could be a spot of economic relief.

Nat Bullard is a senior contributor to BloombergNEF and Bloomberg Green. He is a venture partner at Voyager, an early stage climate technology investor.

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.