Jan 19, 2022

‘Responsibly Sourced' Gas Finds a Niche, But Some Cry Greenwashing

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- From organic chicken to fair-trade coffee, buyers have increasingly shown they’re prepared to pay more for products that meet higher environmental and social standards. The U.S. natural gas sector is wagering its customers will do the same.

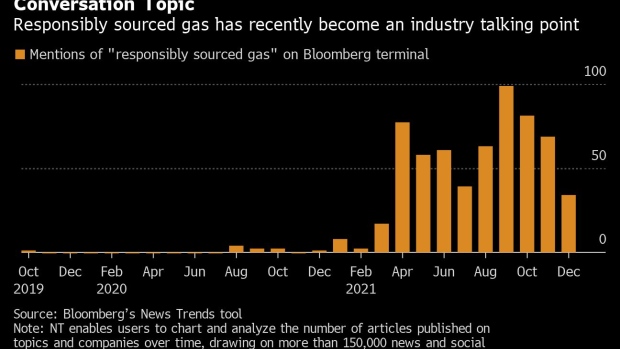

A growing list of companies is getting behind the concept of “responsibly sourced gas,” or RSG. The pitch: Some sources of gas are dirtier than others in terms of the methane emissions associated with production. Utilities under investor pressure to get greener might pay up for the ostensibly cleaner fuel, the thinking goes, making the certification worth the time and money. The idea is rapidly gaining traction among gas evangelists, with one pipeline company estimating operators producing more than a third of U.S. supplies are racing to certify at least some of their output as RSG.

It’s also raising hackles among environmentalists who worry that gas producers are seeking to profit by giving their fuel a green sheen without the energy sector doing the hard work of actually moving to cleaner alternatives such as wind or solar. RSG critics also question the role of the third parties offering certifications and warn that rewarding operators for plugging leaks or improving water use—while undeniably positive—sidesteps the fact that gas is still a carbon-intensive fossil fuel that shouldn’t have a place in longer-term U.S. energy goals.

“We should be doing all of those things and not asking for extra credit and a gold star,” said Cara Bottorff, a senior analyst at Sierra Club in Washington. “We definitely feel that it is a lot of greenwashing.”

Buyers, though, are becoming believers. Although RSG has only been part of the conversation for a couple of years, major utilities like Xcel Energy Inc. and Duke Energy Corp. are already calling low-methane gas a key tool for reaching net-zero methane emissions by 2030. And big-oil producers, shale drillers and pipeline operators alike—from Exxon Mobil Corp. to EQT Corp. to Kinder Morgan Inc.—can’t wait to offer it to them. Recent deals for certified gas have garnered a premium of 3 to 7 cents per million British thermal unit, or 1% to 2% over commoditized gas prices.

RSG taps into the huge interest among corporations and investors in figuring out how to improve their performance of environmental, social and governmental metrics and meet emissions-reductions goals. While many people would rather see the end of natural gas altogether, it’s almost certainly going to be around for decades to come, especially after taking on new relevance during the current energy crisis. In that case, advocates of certification argue, why not make what’s often called the cleanest fossil fuel even cleaner along the way?

“Getting rid of methane emissions would solidify natural gas and the critical role it could play in this energy transition that’s occurring over the next several decades,” said Rob Thummel, a portfolio manager at Tortoise. “The key to all of it is ensuring that there’s legitimacy in the process.”

The push to differentiate lower-emission fuel is in many ways a last-ditch effort by a sector trying to fend off an environmental backlash that’s been quickly gathering pace. French utility Engie SA scrapped a $7 billion deal to import U.S. liquefied natural gas in late 2020 due to concerns about emissions. Fierce opposition from climate activists has killed a series of major pipeline projects and led dozens of U.S. cities from San Francisco to New York to curb gas use in buildings. If the gas industry can “green-tag their commodity,” said Eugene Kim, a director at consulting firm Wood Mackenzie Ltd., “definitely that would be preparing for and also protecting them against environmental public backlash about burning fossil fuels.”

Related: NYC Poised to Ban Gas in New Buildings in Bid to Go Green

One of the industry’s biggest challenges will be deciding what counts as RSG—and setting thresholds high enough that customers take it seriously. Unlike the label “organic” used in the U.S. food industry, there are no government-established standards defining what can be called responsibly sourced natural gas. Since certifying organizations each have their own metrics, critics warn the industry can essentially just set its own low bar and meet it, setting it up for a concerning lack of transparency and potential conflicts of interest.

“This is all private; this is not government. There is no agreement on what the heck responsibly sourced gas means,” said Sierra Club’s Bottorff. “It’s just the companies saying ‘trust us.’”

But for a fossil-fuel industry that tends to support light-touch regulation, most would rather skip the Washington oversight and let independent certifiers play that role, much like credit rating firms Fitch Ratings Inc. or Moody’s Corp. do in the bond markets.

“The problem with regulation is that it usually lags behind what best practices are,” said Soledad Mills, chief executive officer of Equitable Origin, a Houston-based nonprofit funded by donations and fees that certifies energy companies in areas like human rights and fair labor conditions. “What voluntary standards can do is actually try to raise the bar for those producers who are investing in best practices and help them differentiate themselves. Because otherwise, if you’re a company, what incentive do you have to perform better than the minimum regulation?”

Chris Romer, 63, is one entrepreneur trying to turn his for-profit gas-certifying company, Project Canary, into the industry’s preferred standard. Companies that pay to have their operations rated are granted a silver, gold or platinum grade based on their relative performance on a number of metrics, from water stewardship to community needs to, of course, methane emissions. Those emissions are tracked via continuous-monitoring sensors installed at the wells being certified in addition to frequent inspections. Founded in 2019, Project Canary sells its own monitoring tech, the so-called “canary,” a solar-powered device that can detect even small leaks. (Romer notes producers can also use rival technologies instead of paying for Project Canary’s eponymous tech.) More than 700 canaries have been installed in the U.S.

“Uncertified gas will become a smaller and smaller percentage of the market,” said Romer, a former Colorado politician who describes himself as “the last Democrat for fracking.” He wagers customers will eventually refuse to buy fuel from suppliers that can’t stand up their green claims, ultimately putting them out of business. “That same thing that happened with blood diamonds is going to happen in the energy industry.” The company has started pilot programs or cut deals with more than 40 shale explorers, emerging as one of the front-runners in the nascent market.

But under a voluntary standard such as Project Canary’s, companies can hand-pick their best gas fields for certification, advertise them as responsibly sourced in the market and never disclose the carbon footprint for the rest of their wells, Bottorff said. She also questions private firms’ ability to work as independent auditors without oversight from a larger governing body. “They get paid by being able to say, ‘Yes, this is responsibly sourced stuff.’ So it causes, in my opinion, a questionable relationship between client and company.”

Romer strongly disagrees with the criticism. Project Canary “overtly discourages” cherry-picking, he said, and “multiple customers” have pursued certification for 100% of their producing assets, instead of a choice few. Above all, he said, this emerging business model only works if the certifiers maintain high levels of integrity: No one would pay for a label no one trusts.

Project Canary—which has an investment by Quantum Energy Partners LLC, one of the pre-eminent private equity firms in U.S. oil and gas—isn’t the only one trying to carve out a foothold in the growing gas-certification space. Its chief rival is MiQ, a nonprofit focused exclusively on methane emissions. Since MiQ’s framework doesn’t take into account any social or governance issues, some companies seeking its validation also pursue certification for responsible energy development provided by Equitable Origin. MiQ, which doesn't require the use of continuous monitoring equipment at a well level, has signed deals to certify gas assets, including some owned by majors Exxon and BP Plc, covering about 11% of the U.S.’s total output, said senior advisor and former commodities trader Georges Tijbosch.

Generally, natural gas produced in basins such as Marcellus and Haynesville is cleaner than that found in association with oil in the Permian, giving frackers such as EQT and Southwestern Energy Co. an advantage when it comes to snagging certifications. In fact, a large portion of U.S. shale operations already sport emissions rates below industry-established goals used as reference—but certification advocates say companies may opt to further improve operations if the financial incentive is there.

“Once you have the transparency,” Tijbosch said, “the markets will do the rest of the work.”

An MiQ certification costs thousands of dollars in fees, based on the size of the facility. Project Canary accounts for “less than a penny” per million cubic feet of gas, Romer said, without giving a total figure. It’s a price a growing number of gas companies are willing to pay, especially if it keeps their product—their lifeblood—relevant during the green-energy transition. Standardized or not, no one wants to miss out on the chance to break the gas industry’s long-held association with oil and coal.

“Responsibly sourced gas will ultimately lead to enhanced margins and improved economics from greater access to global markets,” Southwestern CEO Bill Way said on a November conference call. Williams Cos., which moves about a third of U.S. natural gas through more than 30,000 miles (about 48,000 kilometers) of pipelines, is working to develop a platform where buyers can set up gas deliveries based not only on the producer’s location but also on the fuel’s verifiable emission profile. Kinder Morgan is asking the federal energy regulator to let it use Project Canary or MiQ ratings to determine which gas can be traded as “responsibly sourced” at its Tennessee Gas Pipeline, a 11,760-mile conduit that transports fuel from the Northeast to consuming regions from New York to Texas Gulf Coast.

And more RSG deals get announced every week.

“This isn’t going away anytime soon,” Wood Mackenzie’s Kim said, adding that within the next couple of years, the vast majority of U.S. gas will be cleaner. “If you’re a producer and you’re not on the bandwagon, you need to hurry up to get on that bandwagon because it seems like every day, we see a producer make an RSG announcement.”

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.