Dec 19, 2019

Sweden's rate hike ends subzero experiment in global test case

, Bloomberg News

Riksbank Ends Negative Rates But Remains Expansionary: Ingves

Sweden’s central bank ended half a decade of subzero easing in a move that will provide relief to the finance industry and a test case for global counterparts experimenting with negative borrowing costs.

The Riksbank, once castigated by Nobel laureate Paul Krugman for what he called a “sadomonetarist” policy of tightening, is risking similar controversy again after it raised its key rate by a quarter point despite evidence of a slowing economy.

Governor Stefan Ingves downplayed the growth outlook in the lead-up to the decision with a focus on the harmful effects of negative policy -- in particular, the danger that ultra-low borrowing costs might stoke risky investing. He also insisted that the measure is designed to be temporary.

The Swedish increase on Thursday marks a turning point in the history of a policy pioneered in recent years by three other European economies as well as the Bank of Japan. The Riksbank had flagged the shift so well in advance that not one of the 18 economists surveyed by Bloomberg expected anything else.

“Inflation has been close to the Riksbank’s target of two per cent since the start of 2017, and the Riksbank assesses that conditions are good for inflation to remain close to the target going forward,” the bank said on Thursday. It also said that the repo rate is expected to remain at zero “in the coming years” and kept a goal of purchasing bonds through so-called quantitative easing until the end of 2020.

The krona was initially little changed against the euro, before gaining about 0.2 per cent by 9:42 a.m. in Stockholm, with most market participants expecting the hike.

After Thursday’s hike, the market is unlikely to get much more excitement from the Riksbank, according to Johan Javeus, chief strategist at SEB in Stockholm. He tweeted that people should “expect highly expansive and highly boring Swedish monetary policy in the coming years!”

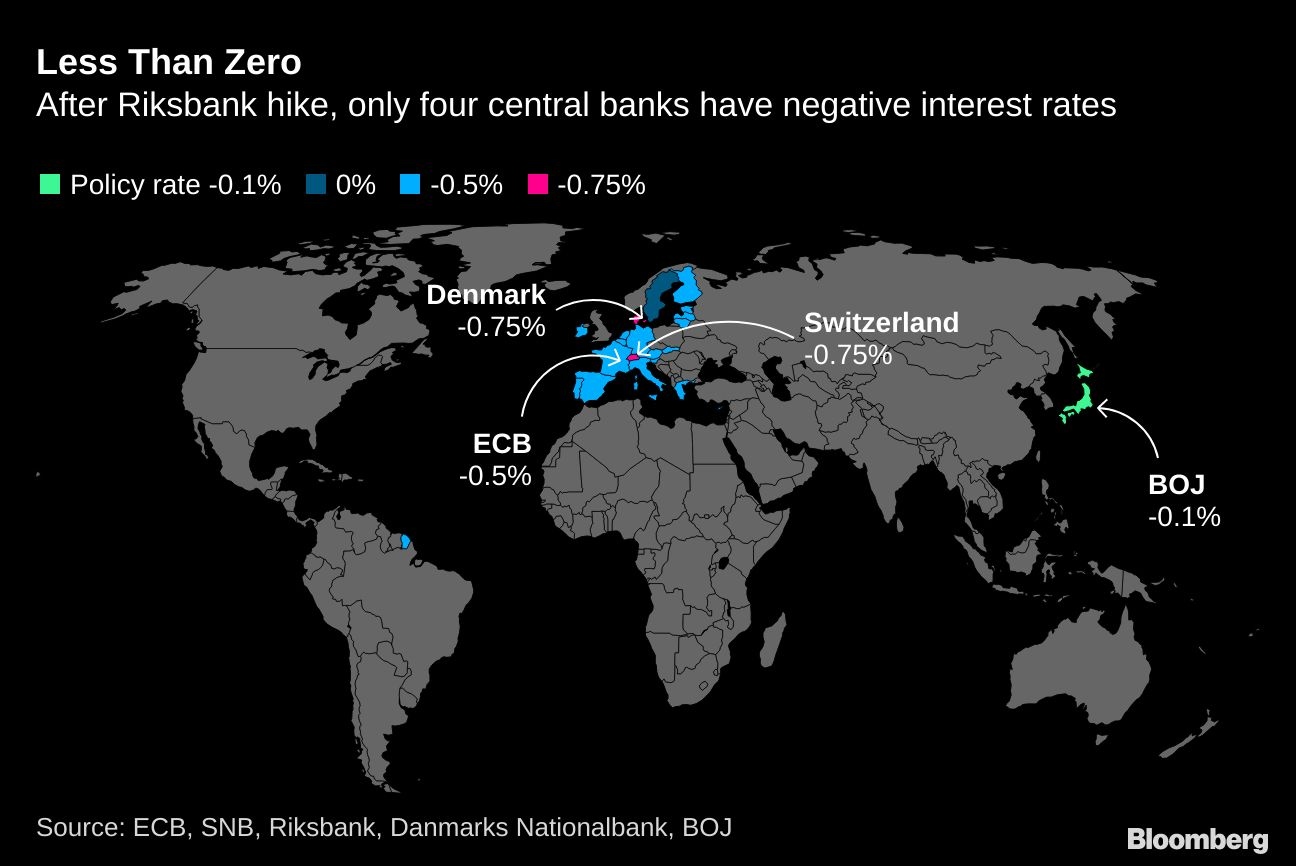

While policy makers have increased their so-called repo rate to zero, the Riksbank’s deposit rate remains in negative territory, though that facility isn’t the pivotal benchmark to borrowing costs in Sweden’s economy. The European Central Bank, the Swiss National Bank, Denmark’s central bank and the Bank of Japan are the remaining institutions currently sticking with subzero policy as a central plank of their monetary stance.

The Swedish move may be watched with intrigue by those counterparts seeking clues on how they might reverse their own negative interest rates in future, if the need arises.

Policy makers often use the measure to stimulate economic growth, in the hope that it provides an incentive to banks to lend money instead of hoarding it.

But ECB officials, whose own rate is now at minus 0.5 per cent after a cut in September, increasingly emphasize the harmful impact of negative rates, from the squeeze on lenders’ profit margins to the threats posed to financial stability by incentivizing investments in riskier assets. A further cut, once seen likely for December, is now rarely threatened by policy makers.

By contrast, SNB President Thomas Jordan has robustly defended the tool and also says that Switzerland can’t be compared to Sweden. While his institution’s deposit rate, at minus 0.75 per cent, matches Denmark’s as the world’s lowest, he refused to rule out further cuts in a newspaper interview published on Wednesday.

The removal of negative monetary policy in Sweden will alleviate pressure on the country’s banking system and investment industry. Richard Grottheim, the chief executive of AP7, which oversees more than US$50 billion in assets from Stockholm, complained in an interview this week that the measure “created a strange situation in the rates market.”

The increase is still fraught with risks. While accelerating inflation gave policy makers a green light to tighten, Sweden’s export-focused economy is vulnerable to trade tensions and showing signs of slowing.

“The Riksbank’s commitment to a hike, at a time when Sweden has also been negatively affected by the global manufacturing-led slowdown, is sometimes seen as counter-intuitive,” Joao Almeida, an economist at Morgan Stanley, said in a note this week. “However, from a cyclical standpoint, Sweden is an economy with a positive output gap and inflation not that far from target.”

If the tightening goes awry, the Riksbank might face the sort of criticism that accompanied the reversal of a previous tightening cycle that had begun in 2010. Policy makers split bitterly and the institution endured repeated public attacks by Krugman.

Former Swedish policy maker Lars E.O. Svensson, a critic last time round, has described the rate increase this month as “a similar mistake.”