Nov 24, 2022

Riksbank Rate Now at 14-Year High After 75 Basis-Point Salvo

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- The Riksbank raised borrowing costs by 75 basis points and signaled more tightening is needed to tame inflation even as it predicted a worsening slump for Sweden’s economy.

In his final decision as central-bank governor, Stefan Ingves and his colleagues lifted the key interest rate to 2.5%, the highest since 2008. Most economists anticipated the move. Officials raised their projection for consumer prices next year and slashed their outlook for output.

“The forecast shows that the policy rate will probably be raised further at the beginning of next year and then be just below 3%,” the Riksbank said in a statement. The risk that “current high inflation will become entrenched is still substantial, and it is very important that monetary policy acts to ensure inflation falls back.”

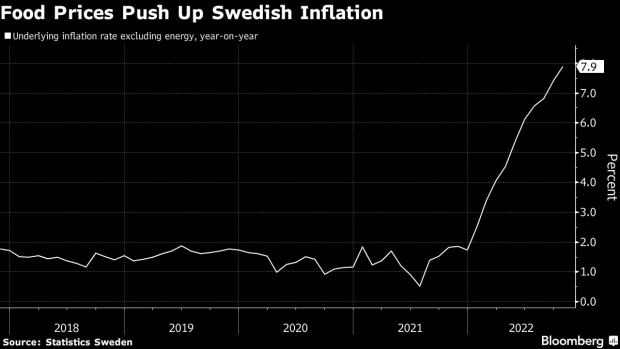

The hike follows data that showed a wide range of goods and services becoming costlier, at a faster pace than expected. It also makes plain the amount of economic pain Swedish officials are openly willing to countenance even as they anticipate further tightening.

“This is a development we haven’t seen in living memory,” Ingves told reporters in Stockholm. “You probably have to go back to the early 1950s to find anything similar.”

The aggression shown by the Riksbank chimes with global counterparts from New Zealand to Iceland, which both kept up a robust stance in monetary decisions earlier this week. By contrast, peers such as the US Federal Reserve are considering shifting to less forceful steps, and the Bank of Korea signaled on Thursday its own tightening might soon end.

The biggest Nordic country is unwilling to be left far behind global counterparts, Ingves signaled.

“It would require something very special happening for Sweden’s interest rate level to be lower than in the world around us,” he said. “That would probably lead to a weaker krona, which would create even more problems when it comes to the inflation rate.”

Swedish policy makers face the challenge of taming prices at a sensitive time. Inflation slowed in October as electricity prices moderated, but an underlying gauge rose to a new three-decade high. The central bank is keen to anchor price expectations before wage talks in the country, which are scheduled to yield a benchmark agreement early next year.

“If inflation becomes entrenched in price and wage formation, a powerful monetary policy reaction will be required,” officials warned, citing an alternative scenario requiring a more hawkish response.

The inflation measure tracked by officials will now average 5.7% in 2023, according to forecasts released with the decision. The economy’s performance next year will be substantially worse than previously predicted, with a 1.2% contraction envisaged.

Given that backdrop of souring prospects for output, concern has risen that the central bank’s actions risk harming the recovery, as consumers already squeezed by rising costs face even more expensive mortgages.

In what may be the most obvious real-economy effect of rate hiking, house prices have dropped by 14% from a peak earlier this year.

Property values “will continue to fall in the coming years, to around the level prevailing prior to the pandemic,” the Riksbank said. “There is a risk that the process of adapting will be more abrupt and that housing prices will fall more than is being assumed now.”

The decision on Thursday is the last currently scheduled for 2022, meaning it’s the final one for Ingves, whose 17-year reign leading the Riksbank is coming to an end. He will be succeeded by Erik Thedeen, the former head of Sweden’s financial supervisory authority, on Jan. 1.

--With assistance from Joel Rinneby, Harumi Ichikura, Love Liman and Ott Ummelas.

(Adds comments from Ingves in fifth, eighth paragraphs.)

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.