Apr 13, 2022

Rogers keeps rising as Shaw deal nears key antitrust ruling

, Bloomberg News

The market expects that the Rogers-Shaw merger will be federally approved: Former Telus CFO

It’s decision time for the people who control the fate of one of Canada’s biggest-ever mergers.

Telecom and cable giant Rogers Communications Inc. has two more hurdles before it can close its takeover of rival Shaw Communications Inc. The $20 billion (US$16 billion) deal needs a green light from the country’s antitrust watchdog and a key federal government ministry. Those rulings could come as early as next month.

Rogers shares rose to near a record on Wednesday, up 0.6 per cent to $74.23 in Toronto, and have jumped 23 per cent this year. Shaw has been marching closer to the takeover price of $40.50 a share, a sign of investor confidence that the transaction will get done. But that doesn’t mean the road will be easy. The biggest looming question is how hard the government will squeeze the company in return for its approval.

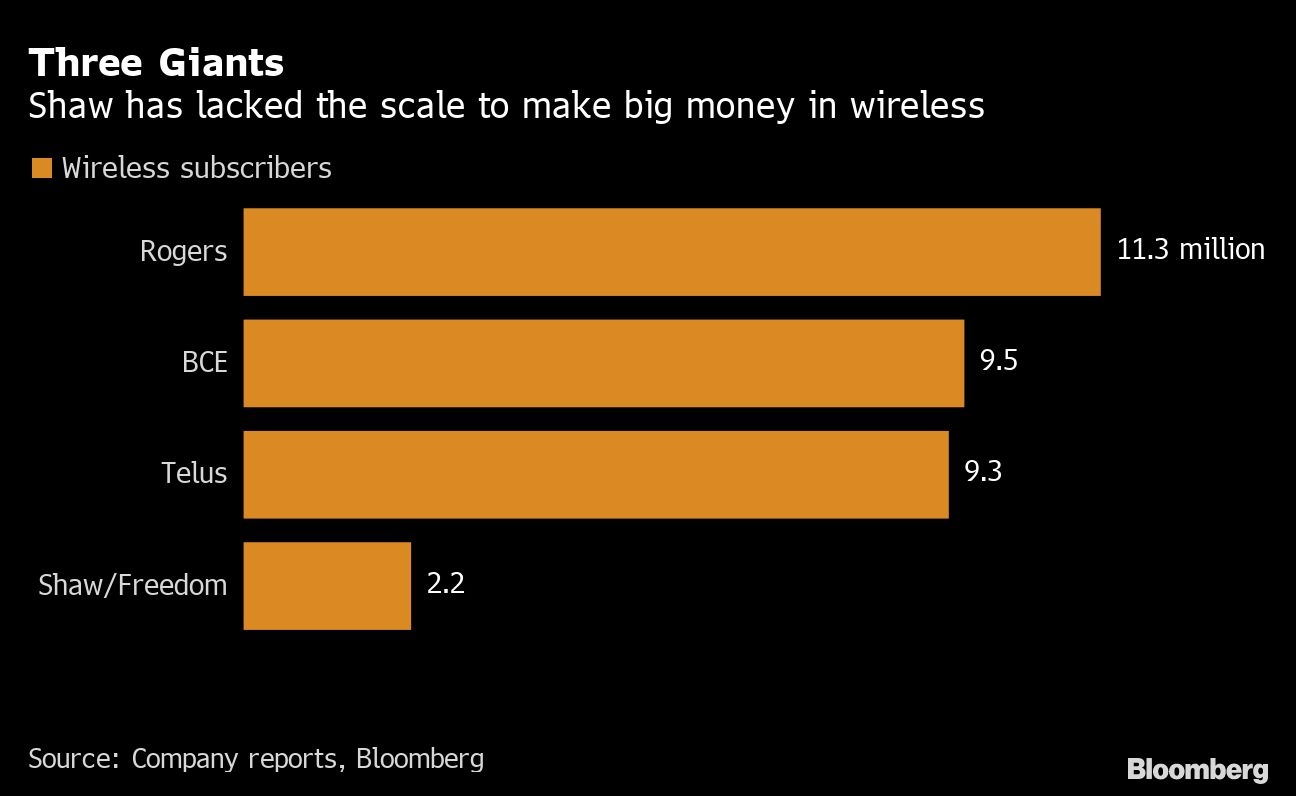

The antitrust review is expected to be the most difficult obstacle. Rogers has long been the biggest wireless firm in Canada. Adding Shaw would eliminate the No. 4 player in key hubs like Toronto and Vancouver. Rogers executives believe the government simply won’t allow that, so they’ve been looking for a buyer for Shaw’s wireless division, Freedom Mobile. It may be worth $3 billion to $4 billion, according to analysts.

But even a divestiture of Freedom Mobile may not be enough to satisfy regulators in a country that has some of the world’s highest wireless bills. And it will be a test for the administration of Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, whose Liberal party pledged in 2019 to force companies to reduce the cost of wireless services.

THE STAKES FOR ROGERS

Toronto-based Rogers found itself in a global spotlight last year because of a family feud over leadership that erupted in the public eye. Before that drama stole the headlines, the Shaw takeover was lauded as fulfilling the dream of the company’s late founder, Ted Rogers.

The acquisition would help Rogers improve its network across western Canada and extend its cable business nationally. It’s the key piece to any successful turnaround for a company that, before this year, had underperformed BCE and Telus for a long time.

Rogers has said it can strip out $1 billion in costs, crucial to helping the company pay down the enormous debt it’s taking on in the takeover. A Rogers spokesperson declined to comment on the ongoing regulatory process.

“If you consider that the deal will happen and all of the synergies that management expect will happen, the stock is definitely too cheap,” said Jerome Dubreuil, a telecommunications analyst at Desjardins Securities Inc.

THE REGULATORY PATH

BCE’s 2017 acquisition of Manitoba Telecom Services Inc. -- a much smaller deal -- could shed light on the path ahead, said Michael Geist, a professor who specializes in internet and e-commerce law at the University of Ottawa.

In that deal, BCE agreed to sell parts of the business, including stores, spectrum and some customer accounts, to Telus and internet provider Xplornet Communications Inc.. BCE was also required to help Xplornet in other ways, such as sharing access to cell towers.

“It provided the playbook for Rogers in trying to get a deal forward and left them with the view that so long as you provided enough goodies, you were likely to get this through,” Geist said in an interview.

Dwayne Winseck, a professor at Carleton University who was consulted by the government on both the BCE-Manitoba and the Rogers-Shaw deals, called the MTS agreement a “complete disaster” because Xplornet didn’t become a strong wireless competitor. The market in Manitoba is now dominated by three providers instead of four.

The same potential problem exists in the Shaw transaction. It’s in Rogers’ interest to help Freedom’s new owners as little as possible, he said.

“What you’re asking a company to do is something that’s diametrically opposed to their interests,” Winseck said, “which is basically to cultivate a new player that’s going to become an effective rival.”

For years, Canada has tried to promote the emergence of smaller firms to compete with the Big Three. But the tide has turned toward a more friendly backdrop for consolidation, Geist said, and approval for the Shaw takeover would further that trend.

“We’ve got a Competition Bureau that has been reluctant to stop deals altogether, and a government that, charitably, has been far more supportive of the telecom players than their predecessors,” Geist said. “It’s a government that doesn’t seem to be willing to take a particularly strong position against those players.”

One reason for the change in tone is the heightened reliance on communications networks during the pandemic as many people worked remotely, Geist said.

“The government may have become more willing to be supportive of those large players given the importance that they play in our society,” he said.

If the deal gets approved, it will probably “drive further market consolidation,” said Matthew Hatfield, campaigns director at OpenMedia, a nonprofit organization that advocates for open and affordable internet.

“This will probably trigger a round of further buyouts and mergers among major players,” he said.