Apr 27, 2021

Rogers victory over BCE in Shaw auction puts key assets in play

, Bloomberg News

Rogers beats analyst expectations in Q1

Rogers Communications Inc. won a bidding war for Shaw Communications Inc. by giving the Shaw family two things it needed most: a high price and deal certainty. Now the question is what antitrust watchdogs will want from Rogers.

Securities documents filed by Shaw on Friday revealed that two companies vied for the Calgary, Alberta-based wireless and cable firm in an auction that lasted for weeks. BCE Inc., Canada’s largest telecommunications provider, matched Rogers’ US$16 billion offer -- but wouldn’t agree to deal language that would have forced it to follow through with the purchase even if regulators attached major conditions. Rogers did.

The filings shed more light into how much regulatory risk Rogers is exposed to in its high-stakes wager to scale up ahead of a massive investment in fifth-generation networks. The Toronto-based company -- which is in the wireless, internet, broadcasting and sports businesses -- is opening itself to scrutiny from regulators across much of its wide-ranging operations.

As proposed, the Rogers-Shaw tie-up would mean less choice for consumers. In heavily-populated parts of the country, only three wireless providers would exist instead of four. Many analysts predict Canada won’t allow that and will force Rogers to sell assets to preserve competition.

Rogers can’t back out even if regulators impose conditions it doesn’t like, under the so-called “hell or high water” clause of the contract. That gives Canada’s competition bureau, and the federal government, some leverage over the company. Both must bless the deal for it to happen.

Rogers Chief Executive Officer Joe Natale told analysts last week the company is charging ahead with an integration plan “that allows us to hit the ground running the minute we get approval” from regulators.

But what will approval look like?

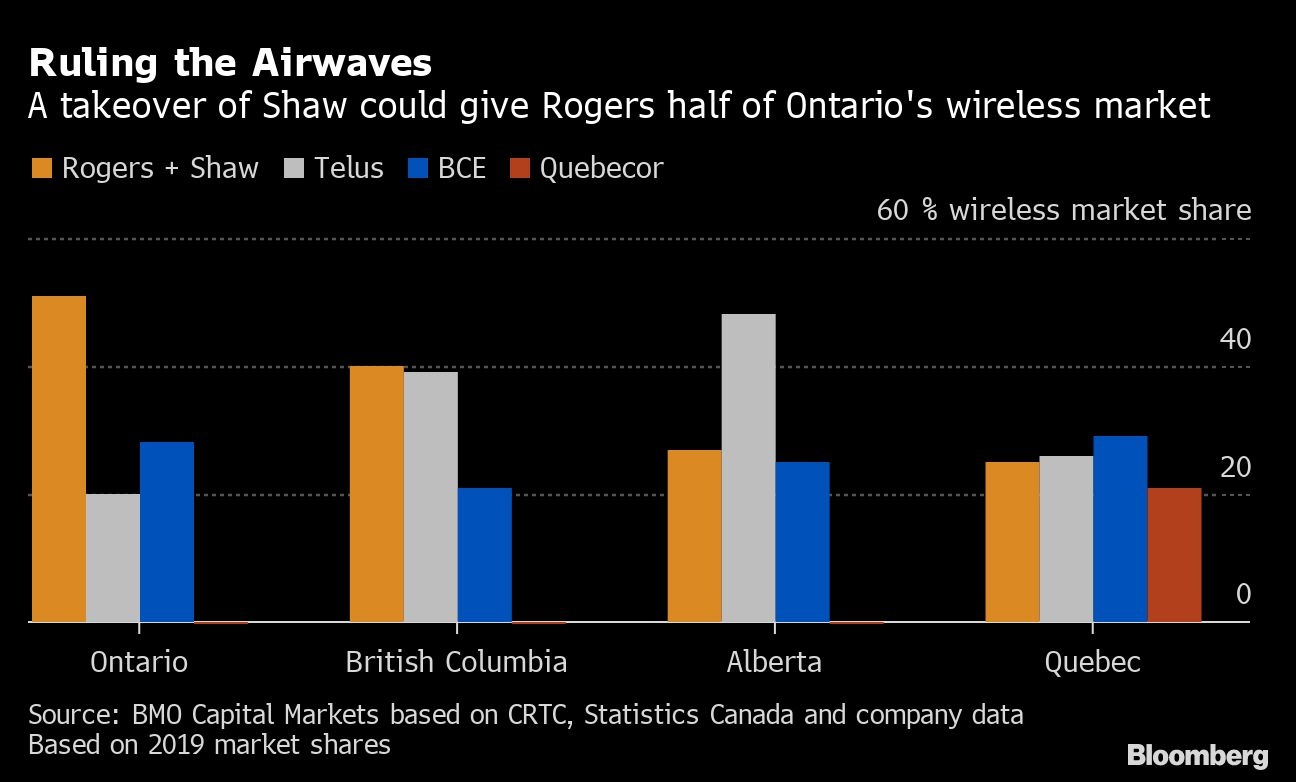

Canadian government policy for more than a decade has been to encourage a fourth player to compete with Rogers, BCE and Telus Corp., three companies that dominate the market. (Government data from 2018 say they had 89 per cent at the time.) Rogers and Shaw, once merged, would have a commanding share of the wireless market in Ontario and British Columbia, two of Canada’s three largest provinces, according to BMO Capital Markets.

“We believe there is a reasonable path to complete the transaction,” BMO analyst Tim Casey said in a report, though it will likely require “remedies on wireless” to get it done.

That could take the form of selling accounts and wireless spectrum acquired from Shaw. There’s precedent. When BCE bought Manitoba Telecom Services Inc. in 2017, it was required to sell wireless spectrum, about one-quarter of MTS subscribers and 19 retail outlets. BCE’s chief legal officer at the time was Mirko Bibic, who is now the CEO who bid on Shaw.

But Shaw is much larger than Manitoba Telecom and the political context is different today, with Prime Minister Justin Trudeau facing a possible election later this year.

Trudeau’s Liberals have pledged to reduce the cost of wireless services by 25% within four years, using the threat of further regulation. In the government’s latest quarterly report on the subject, it said wireless prices for most plans had fallen 10% to 18% since early 2020.

A more difficult scenario for Rogers would see regulators force it to sell all of Shaw’s Freedom Mobile unit. With about 2 million wireless customers, Shaw is the no. 4 player nationally.

However, even that scenario is no disaster for Rogers, according to Bank of Nova Scotia’s Jeffrey Fan. The analyst’s financial model assumes Rogers will have to sell all of Shaw’s wireless assets to satisfy regulators. Conservatively, they’re worth about $2.5 billion (US$2 billion), Fan wrote on April 19.

But the vast majority of Shaw’s case flow comes from its television, internet and wireline phone businesses, and there are large cost-cutting opportunities there -- $730 million worth in operating costs alone, Fan estimates. The merged company will be much stronger, with opportunity to gain share in western Canada and in the business market, he wrote last week in raising his price target on Rogers to $80 from $70. Rogers closed at $61.10 in Toronto on Monday.

Spectrum in Spotlight

One closely-watched item is how the government will deal with Shaw’s spectrum, which can’t be transferred to Rogers without Ottawa’s permission. It’s “likely” the government will force it to give up 600 megahertz spectrum Shaw acquired in a 2019 auction that Rogers was ineligible to buy, Fan said.

For BCE, the key sticking point appears to have been Shaw’s need for certainty. BNN Bloomberg Television reported on Saturday there’s some concern regulators could even force Rogers to sell new 3,500-MHz wireless spectrum that’s being auctioned later this year. (The TV network is owned by BCE’s media division, and has a partnership with Bloomberg LP, the parent of Bloomberg News.)

Rogers declined to comment, instead pointing to earlier comments from Natale that “we feel confident in our ability to strike a good and balanced regulatory outcome.”

The bidding war effectively ended on March 2, when Shaw CEO Bradley Shaw called Bibic to tell him that BCE would have to strengthen the language of its offer, according to the Shaw regulatory filing, though it doesn’t mention BCE or Bibic by name.

Bibic said he wouldn’t, sealing the deal for Rogers, BCE’s longtime rival.

“We’ve made a number of successful strategic acquisitions over the last decade and look closely at opportunities that may work,” BCE spokesman Nathan Gibson said in an April 24 email to Bloomberg. “We determined this opportunity wasn’t in the best interests of our stakeholders.” A spokesman for Shaw declined to comment.

BNN Bloomberg is owned by Bell Media, which is a division of BCE.