Mar 15, 2021

Russia’s Getting Left Behind in Global Dash for Clean Energy

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- As the man in charge of developing Russia’s vast Arctic north, Aleksey Chekunkov faces more climate-related challenges than most, from permafrost sink holes to the emergence of West Nile fever in frozen tundra. Yet he’s no eco-warrior when it comes to fossil fuels.

“We have to be realistic, we are the largest country in the world,” the minister for development of the Arctic and Far East said in a video interview, projecting a 30-year future for natural gas as a mobile, clean alternative to coal. “Solar is not an option for the Arctic region and wind energy isn’t constant.”

Chekunkov’s approach reflects a Russian dilemma: Seen from Moscow, the melting of the polar ice cap is as much economic opportunity as natural disaster, opening the Northern Sea Route from Asia to Europe for shipping and creating access to potentially vast new reserves of minerals, oil and gas.

More broadly, of the bigger geopolitical players — China, the European Union, India, Russia and the U.S. — none risks as much from a successful transition from fossil fuels, if that should happen. Few are as dubious that it will.

“We also know how that’s working out,” President Vladimir Putin said of the transition, during a video call in early March with Russia’s coal industry bosses in which he called for increased exports to Asia. “Texas is frozen and the wind turbines there had to be heated in ways that are a long way from being environmentally friendly. Maybe that will lead to some corrections, too.”

Putin built his centralized political system and Russia’s post-Soviet revival as an “energy superpower” around tight control of state companies and their revenues. Entire regions are dependent on coal or oil for jobs and the social infrastructure that companies still maintain, a legacy of the Soviet era.

In recent years, the Kremlin has bet the country’s economic and geopolitical future on natural gas, building new pipelines to China, Turkey and Germany, while aiming to take a quarter of the global LNG market, up from zero in 2008 and around 8% today.

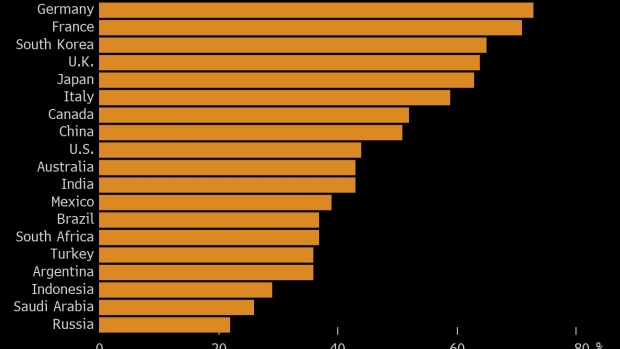

Russia’s strategy, as for Saudi Arabia and other lower cost oil and gas producers, is to be among the last standing as others leave the market, unable to extract at a profit amid falling crude prices. Australia is acting to expand coal exports to Asia while it can, too. But Russia has made less effort to develop a renewable energy industry at the same time.

Putin and other Russian leaders have periodically flirted with outright climate change denial. Scientists have estimated that melting permafrost could cost Russia $84 billion in infrastructure damage by mid-century, while releasing vast quantities of greenhouse gases. Carbon Action Tracker, a non-profit, gives Russia’s climate policies a bottom grade of “critically insufficient.”

Public rhetoric has lately become more cautious, forced by a global shift in attitudes, according to Tatiana Mitrova, head of research at the Skolkovo Energy Center in Moscow. After Europe’s adoption of its Green Deal, China committing to carbon neutrality by 2060 and with President Joe Biden replacing climate skeptic Donald Trump in the White House, Russia looks increasingly isolated.

The question for the Kremlin, Mitrova says, is whether it now opts for real decarbonization, or “some fake reporting, playing with numbers, referring to the carbon absorption capacity of the Russian forests and so on.”

Hers is not the mainstream view. In Russia, fossil fuels are seen as a birthright and the country’s vast distances do pose challenges. Chekunkov, for example, said he’s a big fan of moving to electric cars, but it’s going to take a long time to roll out charging stations across 17 million square kilometers.

No Alternative

“What’s the alternative? Russia can’t be an exporter of clean energy, that path isn’t open for us,” says Konstantin Simonov, director of the National Energy Security Fund, a Moscow consultancy whose clients include major oil and gas companies. “We can’t just swap fossil fuel production for clean energy production, because we don’t have any technology of our own.”Within Russia, natural gas will always be cheaper than renewables and there’s nothing preordained about a low oil price, according to Simonov. It could bounce back with the global economy, once the effects of the Covid-19 pandemic recede. Brent crude traded at $69 per barrel Friday, up from lows of $16 last April.“No one knows how fast the global energy transition will be,” said Simonov. Europe may be decarbonizing, but with demand for cheap accessible energy rising in Asia and India “the trend looks clear, but it actually isn’t.”It wasn’t so long ago that “peak oil” and $120 per barrel prices were the big concerns for net importers. Western security conferences were consumed by Russia’s apparent coercion of neighbors by manipulating the price and supply of the natural gas it sold them through a web of pipelines.

But clinging to Russia’s fossil fuel riches risks huge costs and missed opportunities, according to Igor Makarov, who heads the world economy department at Moscow’s Higher School of Economics.“This perception Russia is a loser in the green transition, that is just in our minds. The best way out of the situation is to understand that Russia has a lot of opportunities to win from the green transition and that it’s in Europe’s interest to help Russia do it,” says Makarov. “It’s much more efficient to reduce carbon emissions in countries where reduction is cheaper.”

Russia’s big private energy and metals companies have started greening their businesses under pressure from international investors. Energy majors, from Arctic LNG specialist Novatek PJSC to state nuclear energy company Rosatom are looking at how to monetize hydrogen production, once the technology is available.Still, it’s hard to see how a domestic market for hydrogen can emerge. Russia has no carbon pricing mechanism, giving companies little incentive to pay a higher price for clean energy. The energy majors have focused on building an export business, but without government support, Russia lags behind Saudi Arabia, Australia, Chile and other nations looking to become hydrogen providers to the world.

In the meantime, Chekunkov is focused on managing climate impacts and anticipating the jobs and tourist income that the melting of the Northern Sea Route could bring to the 5.4 million people who live in the harsh Russian Arctic.

The government expects to be moving 80 million metric tons of cargo through Arctic waters by 2024, up from 32 million in 2020. By Chekunkov’s own estimate, the once ice-bound passage could be open year round to ordinary ships by 2050, drawing traffic from the Malacca Strait and Suez Canal.

“The truth of life for Russia,” he said of any trade off against climate change in a region the state has been exploring and developing for more than four centuries, “is that it is not a dilemma.”

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.