Jan 11, 2021

Russian Women Can Do Anything. Let Them

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Since the start of the year, Moscow’s subway has employed female drivers, one of several hundred job categories opened up to the fairer sex. It’s a welcome return for opportunities formally rescinded two decades ago — even if it came with a special-edition Barbie. Unfortunately, the moves only scratch the surface of changes Russia’s women really need to see in 2021.

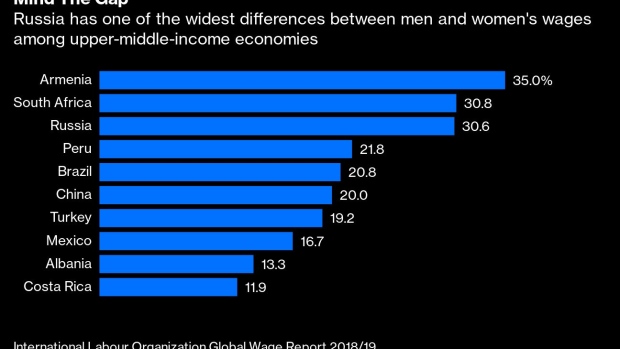

Research shows that while they have historically participated relatively equally in the workforce, Russian women still earn almost a third less than men — one of the widest gaps among high and middle-income nations. As elsewhere, they’ve been more harshly affected by the pandemic given their over-representation in hard-hit sectors like retail and the fact many hold more precarious jobs. They’ve suffered disproportionately, as a result, from frugal state support. Finally, they face the pressures that come with a traditionalist state concentrated on reversing a pattern of demographic decline.

Job limitations do matter. Enshrined in law in 2000, they kept women from 456 occupations deemed too dangerous, arduous or unhealthy, including working as a lumberjack, fighting fires or driving tractors. A 2019 decision to open 356 of those came into effect this year. It’s good news, especially for women in Russia’s traditional company towns, and a symbolic win with economic consequences — together, those 456 roles represent 4% of all occupations.There are still 100 mostly industrial roles that remain formally out of bounds, perpetuating stereotypes and limiting opportunities.

The problem runs much deeper. Russia celebrates International Women’s Day with flowers and a public holiday, and has high-profile female figures like Elvira Nabiullina, governor of the central bank. Yet two in three Russians say they wouldn’t want a female president, according to a survey last year by pollster VTsIOM. Sadly, that figure has risen since 2016.

Thanks to the country’s Soviet legacy, there is female representation, but very few women rise to the top. The World Economic Forum’s Global Gender Gap Report ranks Russia 122 out of more than 150 countries in its 2020 political empowerment index, given, among other things, that less than a sixth of the country’s parliamentarians and less than a seventh of ministers are female.

It’s indicative that one of last year’s most spectacular female political victories was accidental: Marina Udgodskaya, a cleaner in the administration offices of a settlement northeast of Moscow, was strong-armed into standing against her pro-Kremlin boss to legitimize the race. She won by a landslide.

What happens in government is a reflection of resistance elsewhere in society. A 2019 study of public companies found that, in general, the share of woman on boards doesn’t rise above 10%.

All of this is made worse by an increasingly conservative leadership that hasn’t actively supported gender equality and tends to view it through the prism of support for motherhood, like financial aid for pregnant women. Abortion is legal, but increasingly restricted as officials try to bring numbers down without tackling the underlying issues.

So what should Russia do?It can start by safeguarding women at home with strong legislation against domestic violence, the bare minimum to secure progress. Russia doesn’t currently have specific protective measures, and reported cases increased during the pandemic. Discussion on a draft law, which has been criticized by Human Rights Watch as insufficient and opposed by the Russian Orthodox church, has been delayed. Campaigners trying to make a difference for victims, meanwhile, have found themselves under fire from a state wary of non-governmental organizations.

As for the workplace, Moscow can simply lift all remaining legal restrictions on specific occupations. These have an impact far beyond the specific sectors they target, and are sorely outdated.

It can also widen the talent pool. The coronavirus crisis has offered an opportunity for the government to encourage remote working. That could provide crucial options for more women. They’re frequently more highly educated and healthier than their male counterparts, but are often left out of the workforce if they are too far from large, employment-creating metropolises, or caring for children. Better online access can improve skill levels too.All of this would do more for Vladimir Putin’s demographic ambitions than handouts ever could.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Clara Ferreira Marques is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering commodities and environmental, social and governance issues. Previously, she was an associate editor for Reuters Breakingviews, and editor and correspondent for Reuters in Singapore, India, the U.K., Italy and Russia.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.