Dec 7, 2022

Saudi Arabia Sees 2023 Budget Surplus Bump Despite Oil-Market Jitters

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- Saudi Arabia boosted its forecast for next year’s budget surplus compared with projections made just three months ago, in a sign of confidence that its revenues will hold up despite jitters in the oil market and fears of a global economic slowdown.

The government’s latest fiscal outlook, unveiled on Wednesday, showed it now expects to run a surplus of 16 billion riyals ($4.3 billion) in 2023, nearly double a previous estimate of 9 billion riyals. The economy is still forecast to expand 3.1%.

Revenues are now set to reach 1.13 trillion riyals, slightly more than projected earlier, according to the Finance Ministry. Expenditure next year is expected at 1.114 trillion riyals, unchanged from the government’s estimate published in September.

“We are not celebrating the surplus,” Finance Minister Mohammed Al-Jadaan told reporters. “It’s something that we expected, we’ve been working to curtail our spending and to increase our non-oil revenues.”

The world’s top crude exporter is standing by most of its forecasts even as the oil market is close to wiping out its gains for the year. The threat of a recession also looms large because soaring energy costs and interest rates could stymie demand in the coming months.

The kingdom tends to take a relatively conservative view of crude prices in drawing up its budget and doesn’t divulge its assumptions. Al Rajhi Capital estimates that Saudi Arabia is budgeting for Brent oil at around $78 a barrel next year, roughly where the global crude benchmark was trading on Wednesday.

The oil market could look quite different by early 2023, with several potentially historic shifts in supply and demand unfolding in the coming days and weeks.

Top Chinese government officials over the past week have signaled a transition away from the harshest covid containment measures, which have weighed on the economy in the world’s largest oil importer.

Meanwhile, sanctions on Russia’s sea-borne crude exports took effect on Monday, marking the beginning of a European Union and Group of Seven cap on its oil prices at $60 a barrel.

Surplus projections for next year are likely conservative, Al-Jadaan said. International travel returning to pre-covid levels could add up to 2 million barrels a day of additional oil demand, while the reopening of China’s economy may increase that by a further 500,000 to 1 million barrels a day, he said.

“Just these two factors alone would cause some problems to the international energy market because spare capacity is actually very limited,” Al-Jadaan said.

Saudi Arabia expects this year’s budget surplus at 102 billion riyals, up from an initial projection of 90 billion riyals.

Most of that will likely go to the central bank, Al-Jadaan said, boosting reserves have slumped from a high of $737 billion in August 2014 to about $445 billion. There will also be transfers to the National Development Fund, which has been tasked with investing in developing the kingdom’s infrastructure, and potentially also the Public Investment Fund — the powerful sovereign wealth fund.

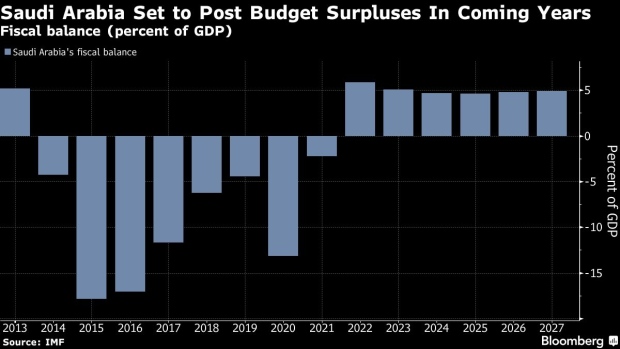

The budget is in surplus for the first time in nearly a decade, and the government wants to keep it in the black in the coming years. That follows several years of painful measures that included reductions in subsidies, alongside more taxes and levies to combat a sharp fall in oil revenue that dented the economy.

Buoyed by the rebound from the global pandemic as well as loosening restrictions on investment and social activities, the kingdom is set to be the fastest-growing economy in the Group of 20 this year with an expansion the government now anticipates will reach 8.5%.

The boom has spread beyond the energy sector. Business activity in Saudi Arabia’s non-oil economy expanded at the fastest pace in more than seven years in November, as new order growth accelerated and businesses turned more optimistic.

Tighter Reins

The kingdom has meanwhile been taking a more conservative approach to expenditure, with the Finance Ministry resisting expectations that surging energy revenue would lead to a jump in outlays.

Al-Jadaan said he’d been asked many times if this year’s surplus would lead Saudi Arabia to return to its “old habits” of boosting spending and insisted he’d keep a lid on outlays.

In the past, budget surpluses had been redirected to a bloated public sector. But this time, the government largely channeled spending increases to help lower-income families tackle the rising cost of living, along with setting a cap on domestic fuel prices.

The outlook remains strong for the kingdom’s finances since it’s among Gulf Arab economies that the International Monetary Fund estimates may save about a third of their oil revenues, a much higher share than previously. The IMF said in October that its projection for the Saudi economy could be revised higher this year on the back of a booming energy sector and strong non-oil growth.

Read More: Saudi Swagger Stands Apart in World of Doom-Laden Forecasts

Still, the latest budget projections signal the Saudi government won’t open the taps on spending. It’s also reluctant to reverse a pandemic era tripling of the Value Added Tax rate to 15%. The move helped shore up government finances when oil prices slumped in 2020, and officials said it would be reviewed in the future.

“The last thing we want is to change policies in haste,” said Al-Jadaan. “Just having one year of surplus or two years and then pushing to change policies is, I think, premature.”

(Updates with finance minister’s comments starting in fourth paragraph.)

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.