Nov 28, 2019

Saudi Arabia Signals It’s Had Enough of OPEC+ Cheating on Quotas

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- For the last year, Saudi Arabia has largely turned a blind eye to cheaters within the OPEC+ alliance, cutting its own output more than agreed to offset over-production from the likes of Iraq and even Russia. Now, Riyadh’s had enough.

Prince Abdulaziz bin Salman, who took over from Khalid Al-Falih in September, will likely use his first OPEC meeting as Saudi oil minister next week to signal OPEC’s dominant producer is no longer willing to compensate for other members’ non-compliance, according to people familiar with the kingdom’s thinking. OPEC meets in Vienna on Dec. 5, followed by the larger OPEC+ alliance, which includes Russia, the next day.

“Saudi Arabia is taking a harder line than in the past,” said Amrita Sen, chief oil analyst at consultant Energy Aspects Ltd. in London. “Riyadh is making very clear that they don’t want to shoulder all the cuts alone.”

The willingness to tolerate cheating was a key part of the “whatever it takes” policy that Al-Falih set out in late 2016, borrowing a line from central banker Mario Draghi.

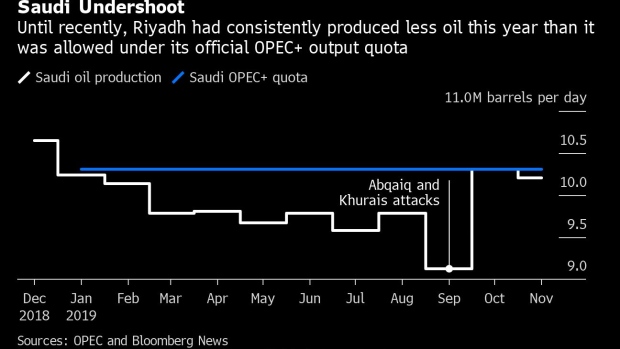

Al-Falih paid lip service to dealing with the cheating, trying to cajole OPEC+ nations to cut output as much as they had promised. But when his admonitions failed and oil prices faltered earlier this year, endangering the initial public offering of state oil producer Saudi Aramco, he simply decided to bear the burden. Earlier this year, in an abrupt change to decades of Saudi oil policy, Riyadh cut production far below their agreed target.

Whether the new policy simply represents a shift in tone, or a more meaningful change isn’t yet clear. Saudi officials privately say Prince Abdulaziz will simply reiterate the decades-long Saudi mantra that everyone needs to contribute to make the production cuts successful. During the tenure of Ali Al-Naimi, oil minister from 1995 to 2016, Riyadh resolutely refused to cut its production deeper than it had agreed at OPEC meetings.

The prince already made the point when he attended an OPEC+ committee meeting in Abu Dhabi is September.

“Every country counts regardless of its size,” he said at the opening session of the meeting.

The cheating has been widespread. Iraq, for example, should be pumping no more than 4.51 million barrels a day; but in some months it produced nearly 4.8 million barrels a day. Kazakhstan accepted a limit of 1.86 million barrels a day, however, it has produced closer to 1.95 million barrels. Nigeria agreed a quota of 1.68 million barrels a day, but has regularly pumped more than 1.8 million barrels a day.

Russia has pumped more oil than allowed by the OPEC+ deal in eight months this year. It has complied with the agreement in only three months of this year -- May, June and July -- when disruption to the key Druzhba oil pipeline pushed production below its OPEC+ target.

Al-Falih was forced to act partly because the kingdom needed a higher oil price to push ahead with the Aramco IPO. But Prince Abdulazziz probably won’t be so constrained once Aramco prices its share sale on Dec. 5, the same day as OPEC’s meeting.

The policy of accommodating cheating has been costly for the kingdom. Riyadh was forced to reduce its own production as much as 700,000 barrels a day below its own OPEC+ quota to prevent oil prices from falling.

In December 2018, Saudi Arabia agreed a production limit of 10.31 million barrels a day through this year. But it reduced production unilaterally earlier this year, reaching a low of 9.58 million barrels a day in July.

As Saudi Arabia had to cut production deeper than others, it’s reaped fewer rewards from the recovery in oil prices. Russia, for example, is earning about $170 million a day more than it did in the final quarter of 2016 when the OPEC+ cuts were first agreed, according to the International Energy Agency. Saudi Arabia is earning just $125 million more.

For OPEC watchers, the test of how far Saudi Arabia is ready to get tough with cheaters is whether the kingdom brings production back to its official OPEC+ quota of 10.31 million barrels a day and sustains it for several months.

The production picture is clouded by the impact of the September attack against two key Saudi production facilities called Abqaiq and Khurais in September. The kingdom depleted its inventories in the days after the attack to sustain exports and Riyadh has subsequently lifted production to re-fill them. In November, the kingdom has been pumping more than 10 million barrels a day, according to people who track Saudi output, significantly above the low of less than 9.6 million barrels a day of July.

--With assistance from Olga Tanas and Dina Khrennikova.

To contact the reporters on this story: Javier Blas in London at jblas3@bloomberg.net;Grant Smith in Vienna at gsmith52@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Will Kennedy at wkennedy3@bloomberg.net, James Herron

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.