Sep 22, 2021

Scholz Is Ready to Turn the Page for Germany in Coalition With the Greens

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- Anyone tuning in to last Sunday’s election debate expecting to see the candidates going toe-to-toe would have been in for a surprise.

Social Democrat Olaf Scholz and his rival from the Greens, Annalena Baerbock, were finishing each other’s sentences and endorsing each other’s ideas, taking turns to attack Armin Laschet, who’s struggled in his efforts to clinch another term for Angela Merkel’s Christian Democrats.

“The CDU should go into opposition,” Baerbock said. “They stand for the politics of yesterday.”

“I won’t make a secret of the fact that I’d ideally like to form a government with the Greens,” Scholz said.

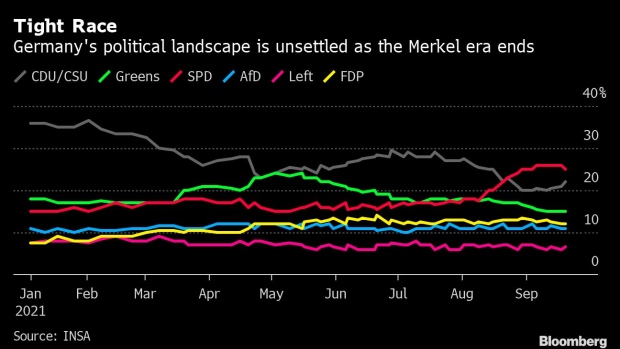

The polls suggest that they might just get their wish.

Scholz’s SPD has maintained a stable lead of around five percentage points through most of September and there are now just four days left until the election. Even if he needs a third party to complete a majority, that would mark a significant shift for Europe’s biggest economy after 16 years of Merkel.

The two parties last governed together under SPD chancellor Gerhard Schroeder from 1998 to 2005. Then the Greens were very much the junior partner — Schroeder once described the Greens as a “waiter,” serving out the policies cooked up by his party.

This time around the power dynamic is different. Baerbock herself was touted as a potential chancellor when the Greens topped the polls in April — and with climate change front and center of voters’ concerns, the SPD has been thinking about how to address the Greens’ concerns.

For union boss Martin Kunzmann, the penny dropped two years at a climate demo in Stuttgart — the heart of car country. On stage with a clutch of young activists, the veteran labor organizer was taken aback by their demands. Inspired by Greta Thunberg’s climate protests, the group were calling, among other things, for an end to combustion engines.

That’s a radical view in Germany’s wealthy southwest, where Daimler AG and Porsche AG employ hundreds of thousands of well-paid workers, many of them in Kunzmann’s DGB trade union federation. Indeed, the 65-year-old machinist, a card-carrying Social Democrat, had criticized the Green movement in the past for placing climate action ahead of social policy, but he decided he needed to be more open.

“I’ll be okay for my last years on this planet, but I have two grandchildren — they want to have fresh air, clean rivers, they want to still have forests,” Kunzmann, the regional chairman, said in an interview at DGB’s headquarters near to where the demo was held. “I can understand that quite well.”

Kunzmann said he and his fellow labor organizers have felt that the Greens let social justice and workers rights take a back seat to environmental issues. But there is now a fresh recognition that climate change needs to be addressed urgently.

In early September, Scholz himself was confronted by a group of climate activists in beer garden near the Spree river while out campaigning in Berlin. He took the opportunity to engage with them and insisted that tackling climate change is “an important issue in this election.”

“Germany is facing one of the biggest transformations in a century — and we will make it happen,” Scholz told the demonstrators.

A potential coalition centered around 63-year-old Scholz and 40-year-old Baerbock would bring together different generations of Germans. The Greens are strongest with younger voters — and those who don’t yet have the right to vote. SPD’s base has traditionally been among the unionized workers of Germany’s industrial regions, an aging demographic.

Both parties want to push Germany to carbon neutrality, phase out combustion engines and ratchet up CO2 pricing with a big public investment push. The main difference is that the SPD has a slower timetable and with less clarity on how much money it is prepared to spend.

The Greens’ skepticism of Russia is one area that sets them apart from the Kremlin-friendly SPD. Both parties reject NATO’s demand for Germany to raise defense spending to 2% of economic output and both want an effective new tax on global internet giants.

As the Greens have left behind their roots in the radical movements of the 70s and 80s, they have developed policy positions outside of their traditional environmental focus and demonstrated a pragmatic approach to the economy. In Kunzmann’s home state of Baden-Wuerttemberg, Green premier Winfried Kretschmann has embraced the region’s robust network of small- and mid-sized businesses and protected auto workers during 10 years in office.

“The Greens have moved to become a progressive central force at the center of the German political system,” Arne Jungjohann, a political scientist who has studied their evolution, said in an interview from the state capital, Stuttgart. “Voters here realized the lights don’t go out when Greens govern.”

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.