Oct 22, 2021

Shell on Path to Miss Own Emission Reduction Goals, Report Says

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- Royal Dutch Shell Plc is on track to miss its own emission reduction targets in the coming decades, even as the company faces more stringent climate requirements from a court ruling, a new study shows.

The energy giant is seeking to gradually reduce its carbon emissions, with the goal of achieving net-zero by 2050. Shell isn’t forecast to achieve its goals after 2022, according to the report by Global Climate Insights.

The company’s energy transition strategy “is still materially driven by fuels that will increase emissions, producing a growth strategy that will not truly align with a decarbonizing world,” it said.

The research casts doubt not only on Shell’s own climate goals, but also its ability to comply with a landmark court ruling in the Netherlands to cut emissions 45% by 2030, compared with 2019 levels. While the company is appealing the case -- a process likely to take years -- it must follow the order in the meantime.

The company won’t meet the target established by the Dutch court “and will instead increase net emissions by 4.4%,” according to GCI. The researcher is an initiative of the Australasian Centre for Corporate Responsibility, a shareholder advocacy group.

“This analysis is highly speculative,” a Shell spokesman said. “We have always been clear that the business plans we have today will not get us to net zero. So, our plans must change over time, as society and our customers also change. We have targets to drive down carbon emissions and a track record in hitting them. We fully intend to meet our future targets, too.”

Carbon Intensity

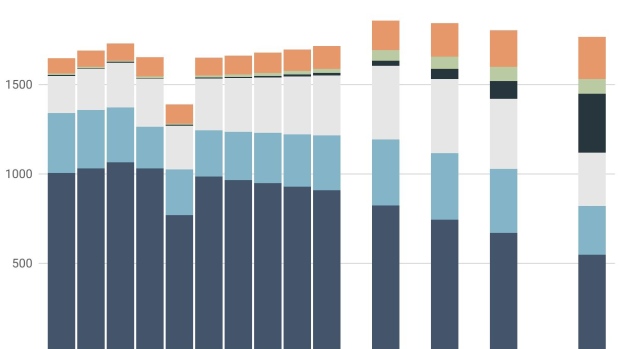

Shell doesn’t have a target to cut absolute emissions by the end of the decade, and it has stated these have peaked. The company’s plan involves cutting the intensity of its emissions -- a measure of the energy needed to produce a unit of oil or gas, for example -- by 20% by 2030. GCI forecasts the major is also on track to miss this target by 3 percentage points.

Shell’s total greenhouse gas emissions were 1.65 billion tons of carbon dioxide equivalent in 2019, around the same as Russia, the world’s fourth-largest polluter. That figure will increase in the next decade because the company’s gas business -- driven largely by liquefied natural gas -- is expected to grow, even though Shell plans to reduce oil production, according to GCI.

Energy giants such as Shell have pushed cleaner-burning gas as a relatively easy way to switch power generation away from coal. But Shell’s volumetric growth in the fuel will far outweigh any emissions savings from that switch, said lead analyst Shu Ling Liauw. GCI expects greenhouse gas emissions from the firm’s integrated gas business to grow 66% in the next ten years.

Paris Goals

If Shell is to align with the 2015 Paris Agreement’s goals of keeping global temperature increases to about 1.5 degrees Celsius, it needs to pursue growth beyond gas more aggressively, according to the report. It also criticized Shell’s plans to expand hydrogen production, much of which will be derived from natural gas.

“Both LNG and gas-based production of hydrogen have little ability to reduce absolute emissions,” it said. The company should reallocate capital into building so-called green hydrogen, which is derived from renewable sources of energy, as well as expanding its marketing business, according to GCI.

The researcher produced the study to increase oversight of companies’ pledges to reduce emissions, which are unstandardized and difficult to compare, according to Liauw.

“Current climate strategies aren’t being scrutinized,” she said. “The market crucifies companies that miss earnings by 1% or 2%. But what we are talking about here is more fundamental, and it gets far less attention.”

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.